The heaviest rainfall in 75 years in Dubai is an unlikely analogy to the current state of geopolitical affairs in the Middle East. A few years ago, the prospect of a direct conflict between Iran and Israel would have brought chills to analysts’ spines. Today, the market seems to brush it off. Are market participants complacent?

This piece addresses the situation in the Middle East, the broader global geopolitical situation, and potential impacts on other Emerging Market (EM) regions/countries. It looks to assess the current situation from an EM participant’s apolitical perspective.

All opinions in this piece reflect the author’s view.

How to frame today’s geopolitical situation?

The current geopolitical global landscape could be described as a “Second Cold War” with China as the partner of Russia and Iran, in a role taken by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) during the First Cold War. The First Cold War was characterised by a dispute for political influence across the world between the United States (US) and the USSR. The two superpowers of the Cold War were not directly firing at each other, but there were several satellite conflicts, such as Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan. The conflicts in Syria and Ukraine can be clearly framed in this context. In a recent article to Bloomberg, historian Niall Ferguson illustrated five key differences between the first and second cold war:1

- The West is economically entangled via various supply chains with China.

- China is a much larger contender to regional power status than the USSR ever was.

- The West is weaker in terms of manufacturing capacity.

- US fiscal policy is unsustainable. Its debt servicing cost will exceed defence spending in 2024. This rule signalled the decline of the Spanish, French, Ottoman, and British empires.

- The US allies, including Germany and India, are more ambivalent than in the Ostpolitik days.2

The two last points are particularly concerning. It is hard to foresee either Trump or Biden reversing the policies (tax cuts and more spending) that led to this situation, given they are central tenets to their political discourses which are part of right vs. left-wing populism. Furthermore, the mercantilist approach adopted by Trump (threatening 10% tariffs across the board and 60% on China) and Biden (subsidies to boost US manufacturing that may also affect Europe) could bring Europe, a region that has been dependent on external surplus to achieve GDP growth over the last decade, closer to its Eurasian trade partners, China in particular, regardless of political differences.

How is the balance of power in the Middle East shifting?

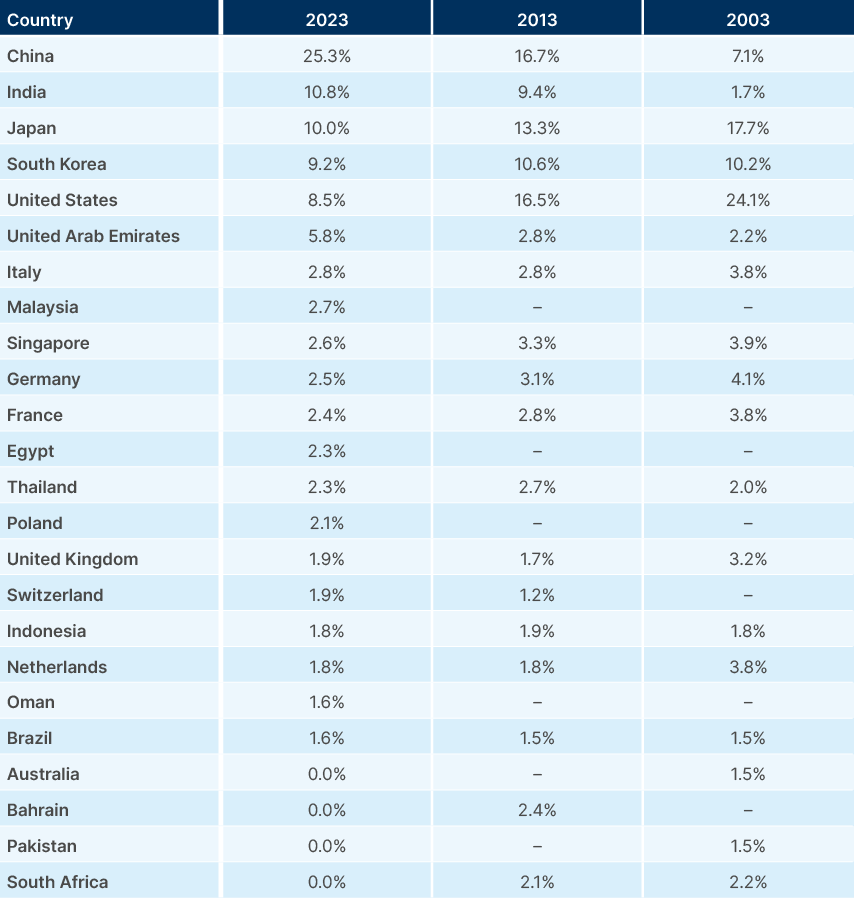

Since the US became a large net exporter of energy over the past decade, the economic importance of the Middle East to the US has been much reduced as per Fig 1. At the same time, China’s dependency on energy imports became more pressing over the last 20 years given the massive expansion of its economy. Therefore, the balance of power in the region is shifting amongst the players.

Fig. 1: Saudi Arabia Total Trade vs. Top 20 Trading Partners

The region’s balance of power has also been shaped by the increased influence of Iran, which gained power via its proxies in Lebanon, Yemen, and subsequently Iraq, and Syria. When America decided to pivot its geopolitical focus to Asia, more space was opened both to global players operating in the region and for the local players themselves.

Both China and Russia have been much closer to the Iranian regime than other large economies. The war in Ukraine brought opportunities to Iran – in terms of supporting the Russians with how to keep a sanctioned economy going – including commercial transactions like selling drones and ammunition. China has always maintained a relationship with Iran and invested in the country as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. China traditionally had a commercial approach to the rest of the Middle East, looking to increase its economic ties in the region. More recently China has expanded its diplomatic clout, making it an important geopolitical player in the region.

Hence, China was responsible for the re-establishment of a diplomatic relationship between Saudi Arabia and Iran for the first time since 1988 last August.3 The deal is an important détente to Saudi Arabia who had its oil fields attacked by drones in September 2019. The attack was claimed by the Yemeni insurgence, but intelligence sources attributed the attack to Iran. A few days after the deal, Iran announced it was applying to join the BRICS group along with Egypt, Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. The Israel-Iran conflict would likely be much more threatening immediately if those accords were not facilitated by China, as the large oil production facilities could be a target for Iranian retaliation.

Another important diplomatic achievement was the Abraham Accords, which established diplomatic and economic relationships between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco. The agreement also provided the conditions for a rapprochement between Israel and Saudi Arabia, a negotiation that is still underway despite the Israel invasion of Gaza. US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan recently told the Financial Times that the Biden administration would not sign a defence agreement with Saudi Arabia if the kingdom and Israel did not agree to normalise relations. Sullivan also linked the Saudi Arabia-Israel deal with a ceasefire in Gaza and the establishment of a Palestinian state.

Saudi is likely to emerge in a much stronger position, most likely with a fresh, more robust security agreement with the US, while at the same time remaining in touch with China and Russia to pursue its own strategic interests, such as selling and refining crude oil in China as well as coordinating oil prices with Russia.4 On 22 April Saudi Aramco announced it is in talks to buy a 10% stake in Hengli Petrochemical.5 This is not the first deal where Saudi has sought to acquire a meaningful stake in China’s petrochemical sector, an alliance with significant synergies and strategic importance.6

The Saudi regime is the most stable of the three big Sunni populations. Its social-economic reforms have been popular, both in Saudi and abroad. This stands in sharp contrast with the situation in Egypt and Türkiye where currency depreciation due to structural problems (Egypt) and populist macroeconomic policies (Türkiye) had a notable impact on the government’s popularity, albeit structural reforms in both countries have significantly changed their outlook. Moreover, Saudi’s stability is anchored by the depth of its relationship with the US.7

India is also an important player to watch. The country has a large Muslim minority population, who are part of the nine million Indian diaspora in the Gulf Cooperating Council (GCC). India’s economic ties with the region will grow as the economy expands over the next years and decades. Like China, India is a net importer of fossil fuels, and its imports are likely to increase as its economy expands. One should expect India to adopt a pragmatic approach to the region, much like its stance with Russia following the invasion of Ukraine. But the relationship will evolve as its size and influence grows.

Several security intelligence agencies claim the US pivot to Asia will render the Middle East more unstable. Markets, on the other hand, are yet to price a significant risk premium to the region or to oil prices. The 7 October Hamas attack brought the region’s geopolitical fault lines back into focus.

It is quite possible that both communities (intelligence and markets) could be right over different time horizons. It is too early to assume Israel won’t escalate matters further, bringing more instability in the near term. Israel decided to invade Rafah, despite significant internal and external pressures for a ceasefire. The helicopter crash that killed the Iranian president bringing fears of an assassination plot is a reminder of the tense situation between Iran and Israel and the US. However, once Israel’s struggles stabilise, the new balance of power in the region may also bring more stability than feared by the intelligence community. Despite the tensions, Iran has been careful to avoid an escalation with Israel or the US that would threaten its own regime. The region’s economy has been improving faster than most anticipated, with commensurate returns available both in equities and fixed income for patient investors.8

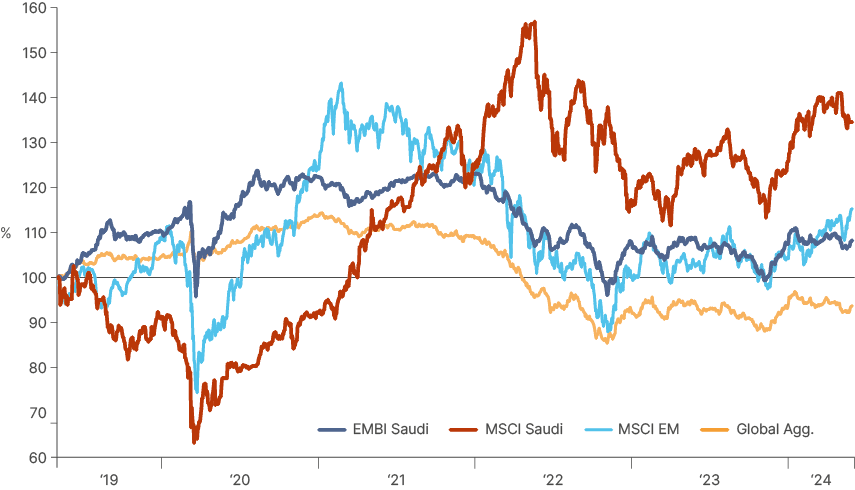

Over the past five years, Saudi Arabian Eurobonds outperformed the EMBI Investment Grade index by 10.1% (1.9% p.a.). Saudi stocks listed in the MSCI EM index rose by 6.1% p.a., outperforming MSCI EM stocks by 16.9% (3.3% p.a.) over the last five years as per Fig. 2.9

Fig. 2: Saudi Arabia Eurobonds and Stocks vs. EM Eurobonds and Stocks

Why does it matter for global markets? Macro spillovers from energy prices and defence spending

Everyone fears a disruption to oil production facilities, say in Iran, or logistical chokepoints (i.e., the Strait of Hormuz) that could bring oil prices sharply higher. This could bring a second wave of inflation like the Russian invasion of Ukraine. There are reasons to believe this risk is well mitigated. The Israel-Saudi Arabia diplomatic relationship and Saudi/GCC-Iran diplomacy both seek to prevent their large and exposed oil facilities from becoming a retaliation target of Iran. Furthermore, if oil production drops in Iran itself – either because of an attack on its facilities or sanctions – the remainder of OPEC has significant spare capacity to manage a shortfall.

Logistically, closing the Strait of Hormuz would affect not only Iranian exports, but also Saudi’s, Qatar’s and UAE’s exports of crude and LNG. That’s why closing the Strait is viewed as the ‘nuclear option’. Iran is unlikely to make any friends by playing this card, and there would be significant pressure (military and diplomatic) to reopen it relatively fast. Closing the Strait of Hormuz is likely to be a short-lived shock, rather than bring a structural change in the level of oil prices.

Moreover, a longer and more aggressive war between Israel and Hezbollah/Iran would also force a steep increase in defence spending, in addition to that driven by Ukraine. This could lead to an inflationary spike, as governments in Europe and the US are forced to increase military spending with their economies operating close to (if not above) full employment.

Central banks are likely to look through the first shock (energy spike) but should be more concerned about the second (higher defence spending) as it would provide stimulus to an economy already at full employment. Nevertheless, it is hard to see central banks hiking policy rates from current levels as the cost of servicing the debt balloons across the West and inflation is currently moving towards their 2% targets (except in the US where disinflation recently stalled). But as Fed Chairman Jerome Powell mentioned at his last press conference, the bar to hike rates from here is elevated. Unless inflation expectations get de-anchored, the Fed would allow a steeper yield curve to tighten financial conditions.

Strategic asset allocation and impact on EM

For many investors, the first instinct is to believe that any event leading to higher volatility is bad for EM assets. It is important to take a step back and think about the global importance of the current events. First, it is not that the dollar is massively strong. Gold prices are up 14% in USD terms year-to-date. Investors are trying to find real assets that will work as a hedge in a multipolar world where major geopolitical events happen much more often than investors have likely been used to. Strategic asset allocation in a multipolar world demands higher geographical diversification into assets that are primarily neutral to geopolitical conflict. Gold may be seen as the ultimate ‘anti-fragile’ hedge, but it has limited space in portfolios as a hard asset that pays no income.

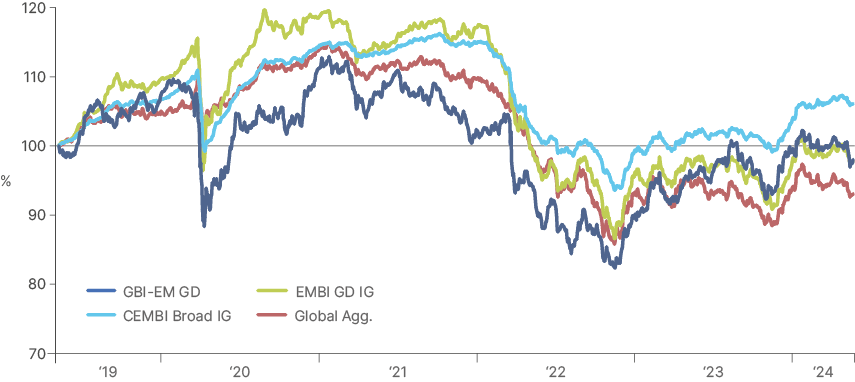

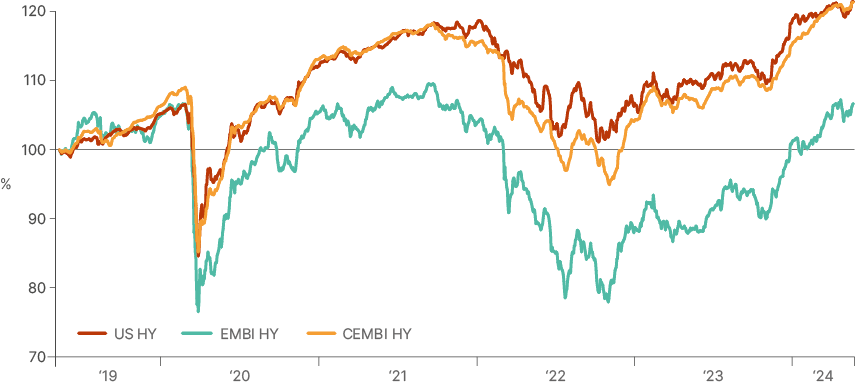

After the twin shocks of Covid-19 and the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, several investors seemed to consider EM assets as ‘uninvestable’. Yet, over the last five years, EM investment grade fixed income assets – both Dollar and local currency denominated – have outperformed the Global Aggregate Index as per Fig. 3. EM high yield corporate debt performed in line with US high yield, as per Fig. 4. EM sovereign high yield is lagging as a few countries defaulted during this period, but the current wave of restructurings and recovery plans have led to 18 months of outperformance of EM sovereign high yield, a trend that is sustainable in several countries, in our view. EM positive performance is a testimony of how well diversified the asset class has become. Most EM asset classes outperformed even though Russian and Belarussian assets were marked at zero post the Ukraine invasion and Ukrainian assets were significantly impaired.

Fig 3: EM IG & LC vs. Global Aggregate

Fig 4: EM HY vs US HY

In the equity space, US stocks have been a bastion of stability. While it is true that the US is a large country, with the largest economy in the world and is not likely to face any wars within its territory, the US does not have the financial capacity to act as the sole hegemon anymore. It has a stretched fiscal deficit while its economy is at (if not beyond) full capacity. US debt/GDP is also at historical highs. The pressure coming from having to support Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan is pulling its (already stretched) budgetary resources further. A few weeks ago, the US Senate passed a USD 95bn aid bill, with two-thirds destined for Ukraine, 18bn for Israel and 8bn for Asia-Pacific. If Israel escalates its conflict, the US may get requests for a much larger cheque.

History has shown that a superpower becomes weaker when it tries to re-assert its position by closing its economy while trying to maintain the military hegemony. If the US does not tame its mercantilist approach and make serious and long-lasting economic-political alliances with Europe and other key allies, it will become more isolated and see its resources stretched. To pay for social security, higher interest expenditures, and security, the US government will have to raise taxes, cut expenditures, or inflate its debt away. None of these factors suggests a disproportionately large allocation to US assets (such as MSCI World’s 71% weight in the US) is warranted.10

From a geopolitical standpoint, unless US isolationist policies (Trade Wars, Chips Act, Inflation Reduction Act) change, the integration of the economies within Eurasia – from Europe and North Africa to the Middle East and Asia – will accelerate. We still believe that the Dollar index is unlikely to see a new high since the USD 114.8 peak in September 2022 (now trading around 105-106) and that US assets could underperform on a three to five-year time horizon. Importantly, the increase in the number and significance of conflicts around the world will illustrate the safe-haven nature of many EM countries.

Asia

The most important geopolitical question in the region lies in the South China Sea. After re-integrating Hong Kong, will China try to take over Taiwan? The result of the elections in Taiwan, with the anti-China party receiving the lowest share of votes over the last eight years, and the pro-China parties gaining a majority of parliament, reduces this risk. What China cares about most is political and socio-economic stability. Although China’s economy is the second largest in the world and has been the largest contributor to global GDP growth for two decades, the average Chinese citizen is still stuck in the middle-income zone. Xi Jinping’s vision is that China needs to focus on investing in new technologies to avoid the middle-income trap.

Taking over Taiwan could most likely be a hindrance to this objective. China’s exports to the global south are growing while its exports to the US are declining, but it still holds a large surplus with the US and Europe. Therefore, China will likely only make a move on Taiwan if it believes it is left with no choice, either because the regime has lost too much popularity locally or because the US imposed sanctions that prevent China from climbing the technology ladder. China’s calculations may change, if it concludes the US is unwilling to engage and that taking over Taiwan will not put it into a direct conflict with the West. We are likely to be very far from both scenarios, which makes for a much more stable equilibrium than most fear, albeit this situation needs to be constantly re-assessed.

North Korea is a major threat since acquiring the technology to produce nuclear weapons, although the reality is that the North Korean regime faces hard constraints. Pyongyang’s economy depends on China (and more recently Russia). An attack in South Korea (or Japan) would be a major shock to supply chains in Asia, something Beijing is very likely to object to, particularly now that its manufacturing machine stands as one of the few bright spots in the Chinese economy. Furthermore, the North Korean leaders most likely know they can not win a war against its southern neighbour as the US is likely to intervene to support Seoul. Therefore, attacking South Korea (or Japan) would represent an existential threat to the regime in Pyongyang, something on which the regime is unlikely to gamble. Hence this geopolitical risk is firmly in the “tail risk” category.

The rest of Asia is a much more stable place. Large countries such as India and Indonesia may well keep pursuing their own strategic interests, balancing their relationships between the political reality of China on their doorstep and the other large markets of Asia and the West. Hence, most EM Asian countries are likely to remain neutral as their geopolitical positioning will guide them to focus on taking action to boost GDP growth.

Central and Eastern Europe

A big question in Eastern Europe is the likelihood of Russia deciding to expand the Ukraine conflict towards a NATO ally. It is hard to understand why that would make sense for Russia. Some will argue Putin is irrational. That may be true. But perhaps Putin and his political allies that keep him in power have a different perspective. If Ukraine converges to the West, as happened in Poland, Hungary, and Romania, perhaps Russians would want the same for themselves. This would present a serious threat to the regime in Moscow, hence drawing the red line. The logic of regime preservation suggests attacking (or even provoking) a NATO country would make no sense as it would present a much larger and imminent existential threat than allowing Ukraine to be embraced by the EU (and/or NATO).

Looking ahead, an eventual second term of Donald Trump could bring significant upside in Eastern Europe. Trump may well play both sides to achieve an objective. He could threaten to “arm Ukraine to its teeth” if Putin doesn’t come to the table and threaten to “drop the support to Ukraine” if Zelensky doesn’t come to the table. The current USD 61bn of aid approved by the US and the larger Europeans’ security defence will give Ukraine financial conditions and weapons to keep the conflict going for longer. Perhaps another year. But Ukrainians are as much outmanned as outgunned. War fatigue has been kicking in. The population may soon decide it is better to let Donetsk and Luhansk (after all, those regions have already been controlled by Russia for a decade) and Crimea go to re-establish normality. A peace agreement is a high bar, but a long-lasting ceasefire, the first step for a peace deal, is possible, under either winner of the US election as both presidents have costs and risk reasons to reach a stalemate.

In such scenario, Ukraine would have access to significant resources from Europe and the US to rebuild its nation. That would massively benefit the Eastern European economies. The reconstruction effort in terms of cement, steel, machinery, workers and all else necessary for the largest reconstruction of Europe since the Marshall Plan will pass through Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland.

Latin America

There are currently no geopolitical threats of importance from Mexico to Argentina. The Guyana-Venezuela dispute appears to be a purely political manoeuvre.

This dispute dates to 1960 and Venezuelans believe that the Essequibo region of Guyana should be part of their country. The referendum asking this question was a ‘slam dunk’ intended to boost President Nicolas Maduro’s battered popularity. Venezuela does not have the resources capable of absorbing any territory today, especially a deep rainforest area that accounts for nearly 60% of Guyana, and the largest players in the region – i.e., Brazil and the US – are unlikely to let it happen.

Since the beginning of the year, Latin American assets have sold off as geopolitical concerns helped to re-price the odds of Fed rate cuts in 2024. In our view, this is an incredible opportunity, both in equities and the fixed income markets. The region is resource-rich, has a large population and is benefiting from expanding its trade as well as receiving a significant amount of investment from China. The election in Argentina most likely set the scene for a centre-right wave in the next round of elections across countries, as so far, it has been proving that economic reforms are possible.

Very important to Latin America will be the evolution of US policy on immigration. The level of illegal immigration to the US hit historical highs in recent years. Opinion polls shows this is the most important theme for Americans ahead of the 2024 presidential election. This plays into Trump’s hand. Trump, an immigration hawk (remember the “beautiful wall”?), will blame Biden for the surge in immigration. If Trump wins the election, one should expect a much more aggressive anti-immigration policy, deportation, and stricter border controls.

Nevertheless, a long-term solution to immigration demands both carrots as well as sticks. The bigger the gap between the economic opportunities in the US and Latin America, the more pressures on immigration will build, regardless of immigration policies. The Venezuelan crisis, arguably exacerbated if not caused by US sanctions, was one catalyst for the recent surge in immigration. Hence, to stop immigration, the US must promote economic development across Latin America. After all, no one wants to leave their homes if they feel financially and physically secure there.

This could be achieved, for example, via more trade liberalisation with strings attached. The US would accept importing Latin American goods and services with minimal duty if key institutional conditions are in place. Some of the thoughtful elements of the USMCA trade deal, such as a framework to increase the minimum wage in Mexico and guaranteeing American investments in Mexico, is a good example of how this could be achieved. This model could benefit other South American countries such as Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela.

Summary and Conclusion

The direct confrontation between Iran and Israel brought geopolitical risk in the region back to the fore. While paths for de-escalation in the short term exist, it is not clear if they will play out, arguably demanding a higher regional risk premium than is currently priced in global markets. Nevertheless, the aftermath of the Israeli struggles may create the conditions for a new, more stable balance of power in the region.

A more complex, but also stable relationship is emerging due to evolving commercial, strategic, and diplomatic relationships, rendering the region much less dependent on the US, and more committed to the EU and China (for trade), Russia (for energy market coordination), and Iran (renewed diplomacy).

The escalation in the Middle East led to a small sell-off in EM assets, particularly investment grade and local currency bonds, as higher military spending and higher commodity prices added pressure on global interest rates. This sell-off was partially reversed by hopes of a cease fire in Gaza. But investors worried about allocating to EM could be missing the big picture.

The reality is that investors are now too concentrated in one single country that has stretched fiscal deficits, debt levels and is called upon to support several allies in a very costly manner - the US. There are opportunities for geopolitical safe havens in EM countries, where investors remain significantly under-allocated. Latin America and significant parts of Asia could benefit from trading with both sides in a geopolitically challenging environment. There is an argument that investors should use the geopolitical volatility to diversify their portfolio geographically across large “neutral” and/or strategically significant countries.

1. See – https://blinks.bloomberg.com/news/stories/SC9XS3DWX2PS

2. See – https://www.cvce.eu/en/education/unit-content/-/unit/55c09dcc-a9f2-45e9-b240-eaef64452cae/b3f1bdcb-928a-497d-96bc-e85a4c77cab8

3. See – https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/8/21/china-brokered-saudi-iran-deal-driving-wave-of-reconciliation-says-wang

4. See – https://blinks.bloomberg.com/news/stories/SCULSET1UM0W

5. See – https://www.aramco.com/en/news-media/news/2024/aramco-in-talks-to-acquire-10-percent-stake-in-chinese-company-hengli-petrochemical

6. See – https://www.reuters.com/markets/deals/chinas-hengli-petrochemical-says-saudi-aramco-talks-buy-10-company-2024-04-22

7. See - ‘Policy direction unchanged post local elections in Türkiye’, Weekly Investor Research, 8 April 2024.

‘The big picture behind Egypt’s big deal’, The Emerging View, 20 March 2024.

8. See - ‘Two birds with one stone?: EM small caps’, Weekly Investor Research, 7 May 2024.

‘Spotting stagflation’, Weekly Investor Research, 20 May 2024.

‘Iran launched an unprecedented strike against Israel’, Weekly Investor Research, 15 April 2024.

9. From 7 May 2019 to 7 May 2024.

10. See - ‘Iran launched an unprecedented strike against Israel’, Weekly Investor Research, 15 April 2024.

‘The case for EM in a multipolar world’, The Emerging View, 24 March 2024.