The Russian invasion of Ukraine is a shock to the existing world order. From an economic perspective, the initial impact of the war is rising inflation given the importance of Russia and Ukraine in the supply of commodities to the world. The economic sanctions imposed by the Western democracies have also lead to increased risks of liquidity shocks.1 Another consequence of the sanctions is the need to diversify reserve assets away from the USD. These events often lead to a market leadership transition and the long US capital markets’ leadership is over-extended and ripe to be overtaken by EM assets, in our view. Many large EM countries have so far kept a neutral stance in the conflict, allowing them to keep their options open in a ‘multi-polar’ world order where China challenges Western dominance. Several EM countries will also benefit from higher commodity prices and the monetary cycle favours EM. The central banks of EM countries experiencing high inflation reacted boldly over the past year, while China is bucking the trend with monetary and fiscal policy easing.

1. Political context

2. The Ukraine war and the big picture

3. Sanctions consequences

4. Global Capital Allocation

5. Capital allocation playbook during wars

6. The role of Emerging Markets

7. Diversification amidst a tightening cycle

8. China

Appendix 1 - Geopolitics: Scenarios for the Russian-Ukraine conflict

Appendix 2 - De-globalisation

The Russian invasion of Ukraine was the first major known-unknown event of the year and is a humanitarian crisis comparable to the wars in Korea, Vietnam, former Yugoslavia, Syria and Libya. In Russia’s foreign minister Sergey Lavrov’s own words, it represents a big challenge to the pre-existing geopolitical world order, with potential consequences beyond the conflict itself.

1 | Political context

The military conflict hits the world after five years of an economic and trade war between the two largest economies – the United States (US) and China – and the most deadly pandemic in 100 years. The pandemic may have played a role in Russian President Vladimir Putin’s decision-making, with him isolated and surrounded by people that are unable to dispute his viewpoints. In the West, covid-19 policy responses had a negative impact on public finances and the economy, focusing minds away from geopolitical threats. Furthermore, the pandemic exposed the fragile state of democracies around the world as inequality had built up over 40 years to an extreme only experienced before the First World War. It was hard to avoid the temptation of excessively easy fiscal and monetary policy after too little action made the recovery from the 2008 crisis more painful than it ought to have been. The policies designed to soften the blow to the lowest income population, namely helicopter money, led to a further exacerbation of inequality. As money was devalued, the poorer suffered the most.

War hit the world as it was healing from the pandemic

2 | The Ukraine war and the big picture

At the risk of over-simplifying, there are two possible principal outcomes in Ukraine. Either Putin wins, after a combination of: (a) demilitarisation of Ukraine, (b) regime change in Ukraine, or (c) the partition of Ukraine; or Putin loses as the Ukrainian resistance deprives the Russian army of these objectives and a peace deal is reached with neither regime change nor the partition of Ukraine.

If Putin were to win, his success in Ukraine may embolden his supporters and allies abroad. The competition between Western democracies and a China-led amalgamation of democracies, anocracies and autocracies will remain in place. The key risk to the world is this economic conflict turning into a military one, which could happen if China overtly supports Russia in Ukraine, if Russia decides to extend the fight beyond Ukraine, or if China decides to make a move on Taiwan. In our view, it is unlikely that China will take any major risks in the short term. In November 2022, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will agree on the leader for the next 10 years and Xi Jinping has made the case to remain in power for another mandate.

It is unlikely that China will take major geopolitical risks before November 2022

The primary economic impact of the Ukraine war is a rise in global inflation. Inflation was already elevated before the war, with producer price inflation at double-digit levels across most G-20 countries and consumer price orders of magnitude above G7 central banks’ comfort zones. The excessive fiscal and monetary policy stimulus during the covid-19 crisis, alongside efforts to reduce inequality, energy transition and developed world (DM) central banks’ stimulative stance despite evidence of rapidly increasing inflation, were the key structural elements driving inflation higher.

3 | Sanctions consequences

The unprecedented sanctions against the Russian financial system, which excluding several banks from SWIFT and the correspondent banking system as well as freezing assets of the Central Bank of Russia (CBR), hit the Russian economy. Following the sanctions, the CBR doubled policy rates to 20% and provided liquidity to the banking sector at the same time in order to counter inflation while avoiding a systemic crisis. Most likely, Russian leaders did not expect sanctions on the CRB, otherwise they would have diversified their foreign exchange (FX) reserves to a larger extent.

At the same time, the sanctions caused several collateral impacts, including higher inflation, increased liquidity risks and questioning the safety of the USD-dominated financial infrastructure. Commodity prices are the key “transmission channel” of the collateral effects.

Sanctions side effects: inflation, liquidity risk and USD-system question mark

Commodities are volumetric markets with relatively low demand elasticity relative to price. The world’s dependency on exports of energy, food and metals from both Russia and Ukraine drove prices sharply higher. Russia and Ukraine exported close to one quarter of the wheat and barley and Russia exported more than one-third of all energy consumed by Europe.

However, the largest buyers of Russian energy- Europe, China and India - are still paying Russia hard currency or local currencies for energy and other Russian products. If an extended conflict shifts public opinion in Europe in favour of more severe sanctions, the food and energy crisis will intensify, forcing countries to tap strategic reserves.

A sharp increase in commodity prices has historically had a destabilising impact on the global economy. Commodity producers out of Russia and Ukraine will benefit from higher prices, while farmers’ costs rise due to higher fertilisers and energy prices, and the latter also hits miners. However, links in the commodities supply chain are already struggling.

Commodity traders need more capital to trade due to higher prices at a time when many transactions with Russia and Ukraine are disrupted. Margin calls in future contracts rose, forcing the cancelation of several transactions and the closure of nickel futures at the London Metals Exchange (LME). The declining bond prices of trading companies shows the market fears for their creditworthiness amidst the liquidity squeeze in the industry. Commodity processors and manufacturing companies will have to deal with higher input prices at a time when their final clients’ purchasing power declines due to higher energy and food prices.

Commodity traders are the first weak-links of the current liquidity shock

Another unintended consequence is the diminished trust in the Dollar-centred global financial system. The value of FX reserves are questionable if politicians can freeze central bank assets after geopolitical disputes.

4 | Global Capital Allocation

The weaponisation of the Dollar-based financial system has caused global reserve managers to pause for thought. The US had just frozen Afghanistan reserves following the Taliban’s return to power, and it did the same to Russia’s reserves after the Ukraine invasion.

The privilege of the reserve currency of the world is enjoyed by the country with the largest military, largest economy and most developed financial system. Of course, the USD convertibility as well as the rule of law of the US keeps the country in a unique position to receive the bulk of global allocations.

If the US is the guarantor of global security and trade freedom, as well as the largest economy and largest commercial partner for most countries in the world, it makes sense to settle commercial transactions and concentrate FX reserves in Dollars. However, while there are no currencies in the position to challenge the USD today, its hegemonic reserve currency status is under threat.

Global reserve managers paused for thought after the USD weaponisation

The decline in US public support to send troops abroad after the Iraq war, the intervention in Syria and the withdrawal from Afghanistan undermined global security guarantees. The US’ signal to Russia before the invasion that it would not support Ukraine with weapons and soldiers, despite the security assurances of both promised in the 1994 Budapest memorandum, was significant.

At the same time, China is the main commercial partner of most countries, except for Canada and some Latin American countries. Therefore it is not surprising that Saudi Arabia is considering accepting RMB to settle oil exports. After all, 20% of all Saudi exports were destined for China in 2019 while the US was only the fifth largest trading partner after India, Japan and South Korea. Saudi also imported nearly 20% of all its goods from China. This large trade exposure means that Saudi could comfortably settle as much as 50% of its oil sales in RMB to pay for its imports, a share that may increase over time.

Since Bretton Woods, when the USD peg to gold was broken, the value of the USD has been contingent on its parity against commodities, and more specifically energy prices. With fossil fuels still accounting for c. 80% of the global energy matrix, a strong depreciation of the value of the USD versus commodities and settling oil and gas in CNY would hit the reserve currency status of the USD, particularly when US consumer price inflation (CPI) is approaching double-digit levels, whilst China’s CPI remains below 2%.

China is the main commercial partner of most countries in the world

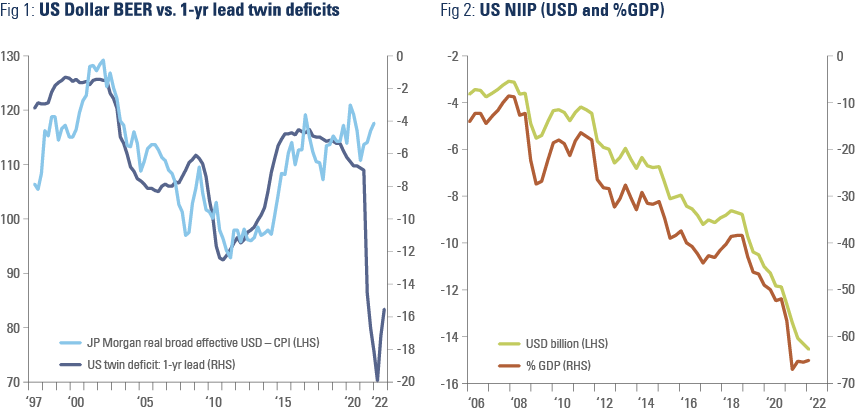

Therefore, global central banks are likely to diversify their reserves outside the USD and EUR systems, making RMB, gold and commodity-backed currencies the most obvious alternatives, in our view. The current USD overvaluation, depicted by the behavioural effective exchange rate (BEER) and external imbalances in figures 1 and 2, suggests the diversification trend is still nascent.

Central banks are likely to diversify their reserve assets away from USD

5 | Capital allocation playbook during wars

Countries that remain neutral during wars can benefit by providing an investment safe harbour due to their lower geopolitical risk profile. Neutral countries are likely to benefit from relatively low risk of economic or physical destruction and as a destination for investments to establish supply chain redundancies. Most emerging market countries, namely those in Latin America, Middle East and Africa (including NATO member Turkey) and most EM Asia, have assumed a neutral position. Conflicts also inflict severe economic pain on losers and provide benefits to winners. Likewise, it is hard to assess who will win the economic dispute between China and the US, hence, the right strategy is to add as much exposure to neutral countries and to diversify risk between both poles of the conflict.

Countries neutral to conflicts, most of them in EM, provide a safe harbour for investors

6 | The role of Emerging Markets

Besides their neutral position, EM also provides proper hedging against inflation due a large number of commodity producing and commodity exporting countries. The unwinding of globalisation will lead to higher production costs for DM companies, unless they outsource their production to other non-China EM countries. After all, any production re-shored from EM to DM is likely to be less efficient and more expensive, given higher labour costs in DM, exacerbating the inflationary issue in DM and increasing the relative advantage of EM.

EM provides inflation hedging

7 | Diversification amidst a tightening cycle

It is hard to build risk-parity portfolios across many countries as Japanese and European yields are negative, and their prices are unlikely to rise much in an economic recession. The higher yield on US Treasuries may lead many to think it could play the role of protecting portfolios against risk-off scenarios. However, the US capital market appears more vulnerable to a recession than at any point in its reserve currency history. After five years of pro-cyclical fiscal stimulus (Trump’s tax cuts and Biden’s pay cheques) foreign investors accumulated USD 13.5trn of US stocks, which compares with only USD 6.5trn of US treasuries. The only G4 bond market that offers both positive real and nominal interest rates is China.

After 5-years of pro-cyclical fiscal stimulus, foreign investors hold USD 13.5trn of US stocks

Furthermore, the Fed has shifted to a hawkish stance signalling a quicker hiking cycle and announcing quantitative tightening (QT) against a backdrop of slowing global economic activity, depicted by declining DM Purchasing Managers surveys. In our view, DM central banks are engaging in a late hiking cycle after remaining behind the curve for at least 12 months, in our opinion.

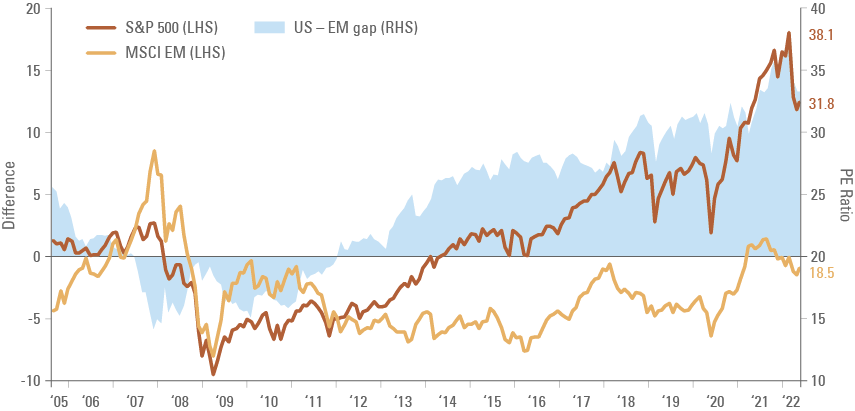

The unwinding of the Fed and ECB balance sheets is also a relative advantage for EM assets. In our view, QT will affect asset prices that benefited from quantitative easing (QE) the most. This means US stocks, the largest source of foreign investors’ claims, are far more exposed than EM stocks. Outsized inflows to US stocks over the past five years are reflected in the large valuation gap between EM equities vs. US equities, shown in Figure 3, which is likely to narrow as the US engages in QT.

Figure 3: Price to (10-year average) earnings ratio: S&P500 vs. MSCI EM

QT will impact primarily US assets that benefited from QE

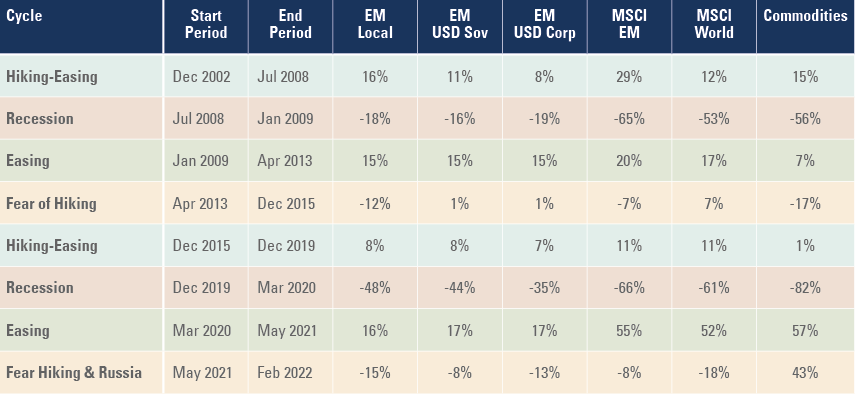

Importantly, figure 4 shows EM outperformed during DM hiking cycles over the past two decades. If the Fed tightens financial conditions excessively (hike until something breaks), EM should benefit from a broad market leadership transition, which always happens following corrections caused by tighter liquidity:

- The Japanese housing/equities bubble that burst in the late 1980s drove capital to EM in the 1990s (EM reforms following re-democratisation and Asian tigers).

- The financial crisis in EM (Tequila crisis in 1994, Asian crisis 1997, Russia default in 1998) drove capital to US technology stocks, leading to the dot-com bubble.

- The burst of the dot-com bubble drove capital back to EM. China’s marvellous GDP expansion benefited EM commodity producers during peak globalisation. This time the tightening cycle broke DM economies again as excesses were accumulated mostly in US households (mortgages) and EU peripheral countries.

- The 2008 mortgage crisis and 2012 European banking/sovereign crisis deflated commodity prices as demand collapsed, while at the same time DM unorthodox monetary policies drove capital from EM into US stocks. These flows accelerated when the US added pro-cyclical fiscal stimulus (Trump tax cut in 2017 and generous covid-19 pay cheques) to monetary stimulus (QE) leading to the currency excesses (USD 13.5trn foreign ownership of US equity market).

- The covid-19 shock led to a “u-turn” on previous monetary tightening from 2015 to 2018, with “helicopter money” driving inflation higher, but also reflating asset prices.

- Finally, the impact of the Ukraine war on global inflation is forcing central banks to “u-turn” again. This time, we are likely to experience a change in asset class leadership from DM to EM, and from tech to commodities.

Pandemic, wars and tightening cycles are triggers for shifts in asset allocation

Figure 4: EM asset class performance vs. monetary cycle

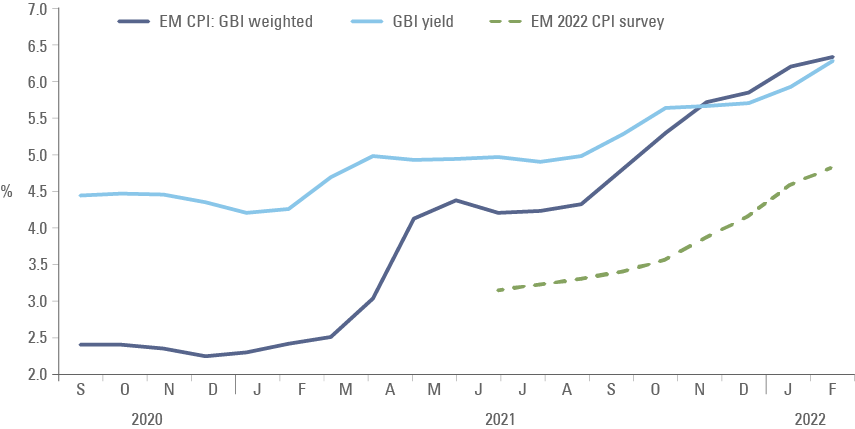

In response to higher inflation, EM central banks have hiked policy rates significantly, a much more hawkish stance than DM peers. As a result, the yield on EM local markets is above the existing level of inflation and year-end expectations as per Figure 5. EM has, therefore, the ability to stimulate their economies, should the Fed hike rates excessively.

EM central banks ahead of the curve, while DM is behind

Figure 5: EM yields, policy rates vs. CPI inflation*

8 | China

China will use its economic weight in its favour, in our view. China is already developing alternative payment systems to reduce dependence on the USD, most likely involving a digital RMB. Reserve managers that are neutral in the current geopolitical conflicts, but have a large trading relationship with China, are very likely to diversify their exposure, in particular if there is RMB convertibility through a better technology than the existing payment system.

RMB bonds offer diversification from USD and protection against a risk-off scenario

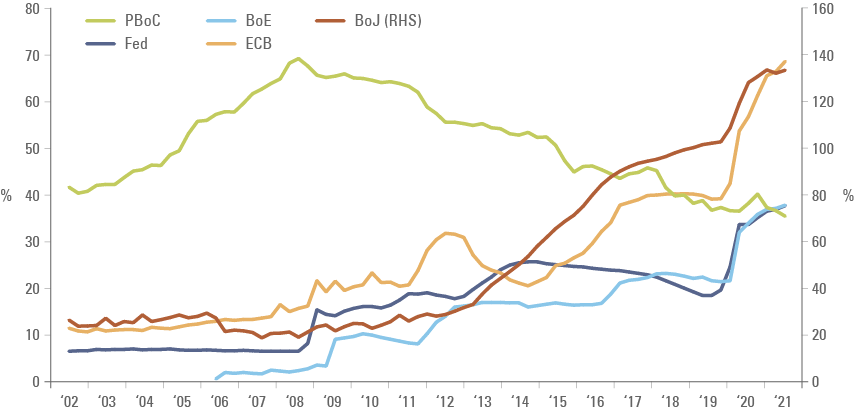

Chinese bonds are one of the few large bond markets that offer protection against a recession/risk-off scenario. China has already started to ease monetary and fiscal policies in 2022 after years tightening monetary and fiscal conditions.2 Since 2008, the size of the PBoC balance sheet contracted as % of GDP while most of the other major central banks in the world implemented QE as per Figure 6. In RMB terms, China has expanded its balance sheet by only c. 2% per year since 2015, a form of passive QT considering the economy has expanded by around 10% per year, in nominal terms. The monetary policy reversal will support Chinese GDP growth, asset prices and China’s main trading partners, in our view.

Figure 6: Global Central Banks Balance Sheet (% of GDP)

Conclusion

The playbook for conflicts is to invest in neutral countries and pick the winner once the picture becomes clearer. We believe asset allocation will shift to more diversified portfolios just as the status quo of the USD comes into question due to the weaponisation of the financial system and high inflation. Against this backdrop, EM offers significant diversification via exposure to countries and companies that are neutral to the conflict and/or stand to benefit from higher commodity prices. China easing monetary and fiscal policy is another headwind from 2021 turning to tailwind in 2022.

Appendix 1

Geopolitics: Scenarios for the Russian-Ukraine conflict

The Ukraine war may accelerate the transition from a world where military and economic dominance is exerted by the United States to a multipolar world as countries become more independent from US security, trade and capital flows. In political terms, several countries will no longer be 100% aligned with different powers, but oscillating between them.

Russia is trying to redraw its geopolitical position via the attack in Ukraine. This is likely to be a strategic mistake and land Russia under the sphere of influence of China, should the war persist for a long period.

Eurasia will have to find a new balance of military and economic power between the US, China and Russia. The war helped to focus European minds on their values and common destiny, as the region’s leaders work towards strategic independence via heavy investments in security and energy.

A renewed focus on the Russian threat is likely to demand Europe to maintain its current strategic economic relationship with China. Europe needs to retain access to the large Chinese consumer markets as well as the Chinese-centred supply chain and technologies (including renewable energy), whereas China will benefit from European technology and quality of manufacturing.

a. The Putin regime downgraded Russia back to USSR status

Putin’s move in Ukraine downgraded Russia back to pre-Berlin wall status. This may change, depending on the duration and severity of the war, the way the war ends, and for how long Putin remains in power. For now the base case scenario is Russia remaining a pariah state for a long period.

Some believe the Russian population will quickly turn against Vladimir Putin because of the economic pain endured by Russia. In reality, Russia still has economic options. It has significant reserves in RMB and gold, its banking system is in good shape, and the economy has low debt levels. Furthermore, any independent media in Russia was purged and the state news are so manipulated that most locals are unaware of the facts in Ukraine and blame the West for the conflict. Centuries of messy revolutions also mean the majority of Russians prefer a strong government than a regime change.

This could change over the coming years if Russia gets bogged down for a long period in Ukraine and the standard of living deteriorates. However, it will be too slow a pace of change to matter for Ukraine. The eventual depletion of military resources is a more important element than public opinion, in our view, forcing the Russians to negotiate a permanent cease-fire.

b. Ukraine

Over most of its history, Ukraine played the role of a geographic buffer zone between the West and Russia, caught in fraught international relations between Europe, Russia and the United States. Its origins date from the Russian Revolution in 1917 when the Germans used Ukrainian independence both as a means of guaranteeing supplies of wheat during the First World War as well as undermining the Bolsheviks.

Its more recent independence was a result of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Ukraine had the world’s third largest fleet of intercontinental ballistic missiles and nuclear arsenal, but had no resources or intention to maintain them. In 1992, Kyiv agreed to transfer the nuclear warheads to Russia for elimination and accede to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as a non-nuclear weapon state. The US was keen to reduce the number of countries with nuclear weapons capabilities and was a strong supporter. In exchange, Ukraine demanded financial compensation, assistance to eliminate missiles as well as security guarantees. In 1994 the US, UK and Russia signed a politically binding memorandum in Budapest committing never to deploy military weapons in Ukraine, unless it was for self-defence. Russia actively broke the agreement while the US did so too by not defending Ukraine. Interestingly a deal between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Ukrainian former President Viktor Yanukovych provided a “nuclear umbrella” to Ukraine, with China pledging to defend it in the event of a nuclear attack.

The West may also bear some share of responsibility as it not only continued to expand NATO after the end of the Cold War, but also said Georgia and Ukraine could, one day, join the military alliance, crossing key Russian red lines despite not being ready to defend these countries. Now that the war has started, what are the scenarios for the conflict?

Scenarios

It is almost impossible to determine accurate scenarios for a conflict, since wars tends to evolve and the final objective of each country changes depending on the situation on the ground. Having said that, it is worthwhile considering some possible scenarios.

Scenario 1: Ukraine accepts Russia’s conditions for a cease-fire

In the first week of March, Russia stated its conditions to end the conflict:

- A demilitarised and neutral Ukraine (enshrined in its constitution)

- Acknowledge Crimea as Russian territory

- Donetsk and Luhansk are independent republics

Encouragingly, President Zelensky has agreed with demilitarisation and neutrality, but said Ukraine will not cede an inch of its territory. The meeting between Foreign Policy Ministers Sergey Lavrov and Dmytro Kuleba also yielded no result, albeit a meeting between Zelensky and Putin was agreed, but is yet to take place.

If a cease-fire were to be agreed, Russia could demand a partial lifting of economic sanctions, particularly if it agreed to contribute to the reconstruction of Ukraine. This is a very uncertain scenario as Western public opinion would be against lifting sanctions. However, considering Russia’s military power and threat it would not be impossible.

Scenario 2: A long and protracted war

The West needs to allow Russia to have its “golden bridge” to proclaim victory and retreat in glory. If not allowed, Putin may decide to keep destroying Ukrainian cities, driving more immigration of Ukrainians to Europe. Ukraine’s patriotic spirit and willingness to remain an independent sovereign means it will keep fighting and is unlikely to subjugate itself to an occupying power.

In this scenario, Europe may decide to intensify economic sanctions by freezing oil imports from Russia. The Russians may choose to stop exporting gas to Europe as well, potentially leading to a further energy crisis and a global economic recession.

Ukraine’s economic fate would be very much dependent on the willingness of the West to assist the country financially. The World Bank and IMF committed USD 2.1bn of lending support, while the US congress approved a USD 14bn package to support Ukraine. These resources will be helpful in a short conflict, but we will be talking about much larger numbers if the war lasts for longer. Boris Johnson discussed the need for a new “Marshall Plan” for Ukraine, exaggerated for now, perhaps not in the future.

Scenario 3: Russia takes Kyiv and installs a “puppet regime”

Under this scenario, Russia may control large parts of East Ukraine and appoint a leader to its territory whereas the Ukrainian president governs from Lviv or even a foreign country. This would allow for some normalisation of economic activity, albeit at an extremely precarious level, and would be a temporary situation as Ukrainian resistance is likely to keep on fighting the Russian occupation. Nevertheless, a very disruptive scenario for the Ukrainian population and assets.

The scenario of a total takeover of Ukraine is less likely, albeit not impossible. It would be very hard to control a country with a larger territory than France where the population is hostile to the occupier.

Scenario 4: Russia broadens the conflict

Another possibility is for Russia to broaden the conflict beyond Ukraine, if Putin feels it has a chance of breaking NATO by, for example, annexing small cities or areas of the territory of a NATO member. While this may seem like a far-fetched scenario, several military advisers have warned about NATO vulnerabilities in the Baltics, including the risk of Russia connecting its exclave of Kaliningrad with Belarus via the Suwalki gap on the border between Lithuania and Poland. The city of Narva, in the Estonian border with Russia, also looks vulnerable, considering close to 90% of the population are ethnic Russians and native Russian speakers.3

Appendix 2

De-globalisation

The US is the largest economy in the world, but a closed one. Its largest companies benefited significantly from globalisation as it outsourced production to more productive countries, mostly centred in the Asian supply chain, at the expense of industry workers in the US. The political backlash against China, thus, is a result of the US failures to support the (smaller) share of the population hit by globalisation.

The attack on the Chinese technology sector, starting with Huawei and restrictions on Chinese access to globally produced semiconductors, was the first shot of the trade war, forcing China to increase its strategic partnership with countries that are willing to challenge Washington’s hegemonic power.

The war in Ukraine is likely to accelerate the reversal of globalisation. Countries that are closer to the Russian sphere of political and economic influence will suffer the most initially. Subsequently, CIS countries may benefit from providing a bridge between the Russian and Chinese economies.

Over the medium to long term the incumbent superpower stands to lose the most from a reversal of globalisation. It is very likely that the Eurasia economic zone centred on China remains significantly more productive and keeps increasing its technological capabilities faster than the US. This is a tricky scenario for global investors who will have to embrace diversification as no asset allocator can afford to concentrate their exposures exclusively in one of the economic poles, considering the risk that it becomes much less important. In the short term, this multipolar world will have different impacts across different regions:

Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)

The CIS countries have the most exposure to Russia. Many were part of the former Soviet Union and will have to find a new place between China, Russia and the West. Some countries, like Kazakhstan, may be in a strong position to benefit from the role of connecting Russian markets to China, after the initial impact of the slowdown of the Russian economy.

A key country to be monitored in the region is Uzbekistan, a country of 34 million inhabitants, twice the population of Kazakhstan. Uzbekistan has been considering leaving the membership of the Eurasian Economic Union composed of Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Cuba, Moldova and Uzbekistan.4

Uzbekistan was the first country in Central Asia condemning Putin’s aggression and pledging to support Ukraine. It would be very difficult for Russia to conduct any operation in Uzbekistan without the support of the Kazakh government. Kazakhstan is at the same time uncomfortable with China’s increased presence in its economy, but also not willing to become a satellite of Russia.

Eastern Europe

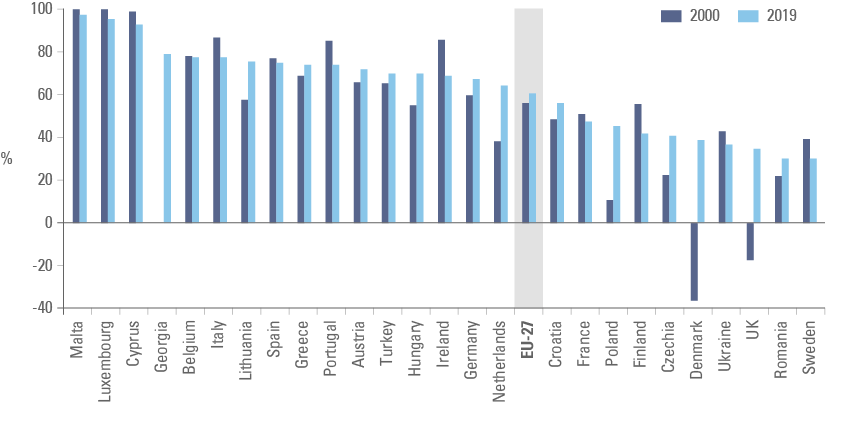

After the CIS, Eastern Europe is the most exposed region to the conflict. Eastern European countries benefited significantly from the Eurozone membership and the integration with Russia following the fall of the Berlin wall. The conflict poses several challenges to the region. First, most Eastern European countries are very dependent on Russian exports of energy. Figure 7 shows Hungary imports 70% of its energy needs, while Poland imports 45% of its energy needs, both predominantly in the form of Russian natural gas, coal and oil.5

Figure 7: EU energy dependency rate by country:

The other negative impact will be in Europe’s manufacturing supply-chain links between Ukraine and Russia. Volkswagen and Porsche announced they would be closing factories in Germany and Poland due to disruptions in the supply chain from Kaliningrad and Ukraine. Thyssen Krupp said it expects significant supply chain disruptions due to the shortage of key metals.

Nevertheless, Europe is already benefitting from a EUR 750bn post-pandemic EU Recovery Fund to invest in infrastructure and energy transition. European leaders are now debating further investments in energy to lower its dependency on Russia. This is likely to support the European economy over the medium term.

The Russian threat also led to better political unity across the EU. In Eastern Europe, far-right leaders in Poland and Hungary have been threatening to change rule of law elements that dissatisfied Europe, bringing these countries closer to Russia. The events in Ukraine forced the far-right parties to pivot back to Europe. Lastly, Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary and to a lesser extent Romania and Slovakia are in a strong position to benefit from Germany’s efforts to boost its military as well.

Middle East

The Middle East is one of the major regions benefiting from the war, with most large countries exporting oil and natural gas, which significantly increased in price. Several countries, including the UAE and Saudi Arabia, made significant progress diversifying their economies and will benefit from an influx of Russian immigrants that became persona non grata in Europe.

Furthermore, the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has not increased oil production, despite geopolitical risks lifting oil prices above USD 100 per barrel. This reflects the new alignment between Saudi Arabia and Russia since 2018, when the latter joined the OPEC alliance as a “plus” member. Since then Russia has been an important partner in determining and enforcing production quotas for the alliance.

The GCC is also deepening its economic integration with China, with Saudi Arabia building a refinery in China while Chinese manufacturer Foxconn invests in Saudi Arabia. The possibility of settling Saudi Arabia’s oil exports to China in RMB is another signal that the balance of power is moving east.

Latin America

Latin America is another major beneficiary from the conflict, owing to its large surplus of commodities, from energy to food and industrial metals (with exception of Central America and Mexico). Another bonus for the region is its geographical position, very insulated from any Eurasian conflicts and in a good position to avoid being caught in influence cross fire between Washington, Moscow and Beijing.

From a historical perspective, Latin America is a good reflection of sea change brought upon by the rise of the Chinese economy. The Monroe doctrine, designed by the US to guarantee its territorial and security integrity, had significant impact across the region. Around a century ago, Panama separated from Colombia after the intervention by the US, which was then interested in constructing the canal.

During the cold war most Latin American countries were targeted by military coups supported by the US. The intention was to avoid these countries falling to socialist regimes supported by the Soviet Union, but also providing a platform for US companies investing across Latin America. During the 1980s, most Latin American countries re-democratised and implemented structural reforms after the fall of the Berlin wall, but the US remained the main trading partner across the continent.

This changed over the past 20 years. China is now the most important trading partner across most South American countries, with the exception of Colombia. China is also developing close economic relationships with several countries, including Ecuador, Venezuela and Argentina. Latin American countries would do well to avoid picking political sides, but the path of more trading with Asia is a path of no return, in our view.

At the same time, the US will probably try to regain its influence in Latin America via significant strategic investments in order to rollback Chinese influence. The US is likely to engage with Venezuela, potentially unwinding sanctions to boost oil production. Venezuela has significant room to ramp up oil production as the country used to produce 2.5 million barrels of oil per day a decade ago. Its oil production declined to around 300k barrels before rising to c. 800k barrels after the country dollarised its oil industry. At the same time, lifting sanctions and trading with Venezuela would help to lower the importance of Iranian and Russian ties developed following sanctions.

Asia and China

After the Russian invasion in Ukraine, all eyes turned to China. Taiwan is the most obvious geopolitical fault line at risk with disputed islands across the South China Sea becoming sources of attrition.

Predicting geopolitical outcomes is a challenging task. However, an educated guess would suggest the Ukraine resistance and the impact of sanctions on Russia would make China more cautious in trying to reclaim Taiwan with force over the short term. Another interpretation suggests the events did not change China’s approach. While the Putin regime in Russia was increasingly anxious about running out of time due to the fast development of the Ukrainian economy and its increasing alliances with Europe and NATO, China believes it has time on its side. After all, China’s economic growth is likely to remain above its peers, allowing it to allocate a larger budget to the military while deepening economic ties across Eurasia to a point where most countries, when faced with the choice between China and the West, would choose the former.

In our view, China will tread a careful balance and will seek to take advantage of cheaper energy and food from Russia in an indirect way in order to avoid being the target of US sanctions for doing business with Russia.

1. West, or Western democracies loosely defined since Japan, Singapore and South Korea joined the sanctions.

2. See weekly 21 Mar 2022

3. See https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/natosource/nato-s-vulnerable-link-in-europe-poland-s-suwalki-gap/ and https://www.thecipherbrief.com/the-outlier-what-if-putins-real-target-isnt-ukraine

4. See https://thediplomat.com/2021/11/uzbekistan-still-contemplating-eurasian-economic-union-membership/

5. See https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/infographs/energy/bloc-2c.html#carouselControls?lang=en