Preparing for volatility: The debt ceiling and the end of US exceptionalism

The US debt ceiling negotiations brought considerable volatility to market prices. While it is almost impossible to predict exactly how it will be resolved, the most likely outcome is for an eventual deal to either temporarily suspend the debt ceiling or an agreement where the White House is forced to cut expenditures to increase the ceiling, as took place in 2011. The recent widening in US Treasury yields may present an opportunity to add duration exposure on investment grade portfolios, which remains a hiding place in a turbulent scenario for investors. However, the debt ceiling episode is also inviting questions about the status of the US Dollar as a global reserve currency, as well as its expensive valuations. Long-term investors are taking note and have been adding exposure to Emerging Market (EM) local currency bonds, which have outperformed USD-denominated fixed income assets year-to-date.

What is the debt ceiling?

The debt ceiling is a Congressional provision designed to force the Executive to discuss its fiscal policies before being able to issue more debt. Since 2006, Congress has increased the debt ceiling 20 times, suggesting the US has a (forced) discussion on the provision around every ten months. This year, the debt ceiling was reached in January and the US Treasury has since been using special measures (such as delaying payments to social security funds) to keep funding its normal operations (payrolls, suppliers, etc.) and debt repayments. Markets initially expected the US Treasury to run out of money from July to September, but Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen revised the ‘x-date’ down to 1 June due to lower levels of tax receipts in April. More recently, higher interest payments on debt servicing led to a faster depletion of the Treasury General Account (TGA) with the Federal Reserve (Fed) to only USD 88bn as of 15 May. What makes the negotiations significant this time is that the Republican Party has a majority in the House of Representatives, which is tying a debt limit increase to concurrent spending cuts.

Republican deal

A few weeks ago, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy approved a bill with USD 4.3trn of fiscal consolidation over the next ten years to raise the borrowing cap by USD 1.5trn. The Democratic Party will not accept either condition, as the fiscal consolidation is too aggressive and raising the ceiling by USD 1.5trn would most likely require a new debt ceiling negotiation before (or right after) the 2024 Presidential Election. The conditionality echoes the difficult negotiations to lift the debt ceiling in 2011. Back then, the Obama administration was forced to accept a package of USD 917bn – around 5.9% of the 2011 gross domestic product (GDP) – in spending cuts withing 10-years to lift the debt ceiling by USD 900bn.

Democrat alternatives

Whereas President Joe Biden is trying to dissociate a higher debt limit to spending cuts, we expect it will be hard to avoid agreeing to a certain number of cuts. Assuming the 2011 playbook of equal amounts of debt ceiling increase and expenditure cuts, and the average increase in the ceiling since 2017, we see a compromise scenario of USD 1.5trn to USD 2.5trn expenditure cuts over ten years, which would be equivalent to 6% to 10% of GDP. The low end of the spectrum could be an equivalent fiscal consolidation to the 2011 deal.

Scenarios

We believe, there are two possible scenarios on how it will play out. A deal could be reached to increase the debt ceiling, involving fiscal consolidation, or a ‘punt’ to suspend the ceiling until the budget discussion in September 2023. There is also the possibility of Congress failing to reach a compromise with the White House until after the ‘x-date’ when the US Treasury runs out of money before a deal is reached.

A doomsday no-deal scenario is almost unthinkable, as the US would have to implement a gargantuan fiscal consolidation to generate a surplus and repay interest on the debt, or default on its obligations, either way leading to a severe recession. Not even a strong fiscal hawk would be willing to be politically responsible for such an event. Yellen said that calling the ceiling unconstitutional (the 14th amendment) is not a viable option. Neither are ‘outside of the box’ ideas like minting a USD 1trn coin. Therefore, while going through the ‘x-date’ is possible, that would be likely to generate only temporary government shutdowns and arrears as the Treasury would probably prioritise servicing the debt. The `x-date` is also somewhat uncertain as it depends on fiscal revenues which are not smooth. In an extreme scenario, the Fed could swap defaulted T-Bills for non-defaulted T-Bills as there is no cross-default across bonds in the US, and the debt would eventually be serviced again.

The end game

We believe the above scenarios suggest it is only a matter of time before the Biden administration accepts some degree of fiscal consolidation over the next three months to resolve the debt ceiling impasse. The question is when it will happen and the magnitude of fiscal consolidation. A USD 1.5trn fiscal adjustment over ten years would be equivalent to what Barack Obama agreed to in 2011, while a larger USD 2.5trn (circa 10% of GDP) would likely be a much more meaningful consolidation. On 17 May, markets received a shot of adrenaline when the ‘technocrats’ got involved in the negotiations, raising hopes of an agreement.1 It remains to be seen if they will be able to convince both the Republicans and the Democrats to find an acceptable compromise, considering the importance of the liberal Republicans and progressive Democrats in the political stability of each party. More recently, markets have been worried about the possibility of going beyond 1 June without a deal, considering the minimum three-day period Congress needs to evaluate (and negotiate) any bills and the next Memorial Day holiday (Monday 29 May).

Lessons from 2011

In 2011, markets traded in a classic risk-off mode going into the debt ceiling negotiations. In our view, the debt ceiling itself had only a small, if any, impact on market direction. Looming large was the prospect of a breakdown in Europe as peripheral countries struggled to refinance their debts, contaminating the European banking system in a negative feedback loop. At the same time, the large Chinese post-global financial crisis fiscal stimulus was getting scaled back, driving commodity prices lower. EM assets were trading at expensive valuations after a decade of extraordinary returns. Hence, the conditions were set for a classic risk-off event. The yield-to-maturity on US high yield bonds widened from 6.61% in mid-May to 7.51% at the end of June, and then soared to 9.5% at the end of September. The MSCI World Index declined 18.5% over the same period and EM currencies depreciated 12.3% from the end of July to mid-September. Not surprisingly, yields on ten-year US Treasuries rallied as the recessionary scenario brought markets to price no rate hikes for a long period of time, as per Figure 1. In fact, the US downgrade by S&P had a very short-lived impact on US Treasury yields, mostly due to the global macro picture. It was not credible that the debt ceiling debacle would lead the US government to default in our view, but it was self-evident that premature fiscal consolidation in a complicated world would lead to a much weaker growth picture.

Fig. 1: 10-year UST yields and debt ceiling events

The impact on America’s credit rating and the US Dollar

Ratings agency Fitch has warned that even a temporary default could lead to a downgrade to the US AAA rating. In 2011, S&P downgraded the US credit rating to AA+ two days after the deal to lift the debt ceiling, as higher political risk clearly increased the odds of a US (at least technical) default.

This latest debt ceiling debate is happening against a backdrop where investors are already questioning the status of the USD as the hegemon global reserve currency.2 It is therefore likely too, that the demand for US Treasuries from foreign investors including central banks, sovereign wealth funds, pensions, and insurance companies remains low. Indeed, the foreign ownership of US Treasuries have been slowing as foreign ownership of Treasuries declined to 30% of total in December 2022 from 40% in 2019. For example, several central banks have been diversifying their reserves to other currencies as well as precious metals.

The problems in America’s regional banking sector have been generating a significant tightening of credit conditions, which is unlikely to be resolved until interest rates decline further. Institutions have still not adjusted the value of their assets to a much higher interest rate environment, while credit conditions are already the tightest since 2008.3 In fact, several leading indicators have already been signalling a recession for some time, in our opinion.4 We think the loss in confidence in the US, a fiscal consolidation, or both, would most likely trigger a deeper market reaction that would accelerate the ongoing economic slowdown. Accepting a severe fiscal consolidation on the current fragile economy will add fears of an incoming economic recession.

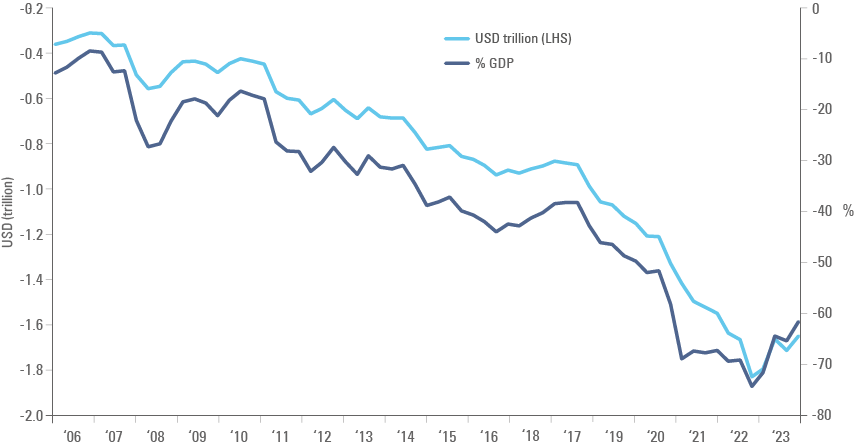

On the other hand, if and when the debt ceiling is lifted, the large issuance of Bills and Treasuries purchased by foreign investors could provide a short-term bid for the USD. Should interest rates rise because of an increase in the debt ceiling, the USD would rally first. This could be a tremendous opportunity to diversify away from the ‘greenback’, which currently trades at historically extreme levels as per Figure 1, and has significant external vulnerabilities, summarised by the massive net international liability of the US in Figure 2.

Fig. 2: US net international investment position

Current macro conditions

The debt limit debate comes after the most aggressive monetary policy tightening shock since 1980s, with the Fed Fund rates pushed to 5.25% and one year of quantitative tightening. The Biden administration has kept pushing for more fiscal spending (e.g., via the Inflation Reduction Act), which has supported the service sector by a stronger degree than expected so far in 2023.

Despite the service sector running hot, we believe there are plenty of signs that we are in the final innings of a late cycle. The Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS) showed demand and supply for credit falling off a cliff, suggesting the most aggressive tightening in lending standards in years.5 The banking sector crisis is far from over. Not only are banks fighting to retain their retail deposits to remain in business, over the medium term, higher interest rates will likely have a large impact on their loan portfolio, as companies and individuals may not be able to accept much higher interest rates on their debt. Office real estate, retail, and shopping malls in some areas in the US are likely to struggle. Elsewhere, residential real estate is already suffering a steep correction in places like Scandinavia, Australia, and Canada. The manufacturing purchasing managers indices (PMIs) have been mostly below 50 since September 2022. It is rare to see the service sector holding up while manufacturing and construction remains subdued.

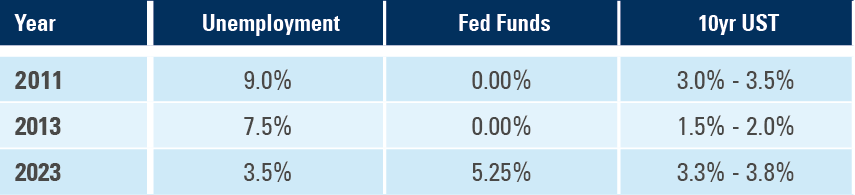

Another factor suggesting the US economy is in late cycle is the unemployment rate. In both the 2011 and 2013 debt ceiling episodes, unemployment rate was at 9.0% and 7.5%, respectively. Today, it is at 3.5% as per Figure 3. The yield on ten-year US Treasuries is hovering around 3.3% to 3.8%, close to 2011 levels, but the Fed Funds rate today is 5.25%, much further away from the near zero band it was at in 2011 and 2013.

Fig 3: Unemployment, Fed funds and 10yr UST range 2011 and 2013 vs 2023

Fiscal and funding imbalances

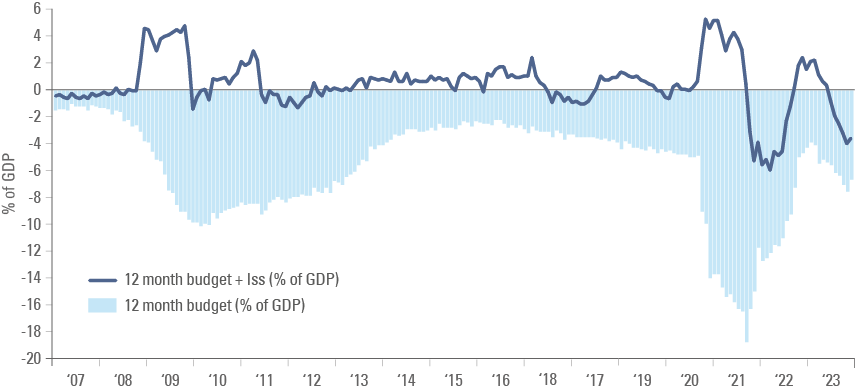

US Treasury yields could move a bit higher before they decline. That would be possible if the President (and Congress) agree to increase the debt ceiling or suspend it until September, or if a deal gets agreed with small and mostly backloaded cuts on expenditure. We expect this would mean the ongoing fiscal excesses would have to be financed in the market, in an environment when the Fed is engaged in reducing its balance sheet, which means the US Treasury would need to issue a significant amount of bonds and bills to replenish the TGA, pay the postponed contributions to the various funds it has been skipping since January, and finance the large fiscal deficit. All-in-all, the US Treasury may be issuing between USD 1.0trn and USD 1.5trn in a couple of quarters while the Fed quantitative tightening reduces its Treasury holdings by USD 85bn per month.

Figure 4 highlights the large and increased budget deficit run by the US and highlights that the deficit was mostly funded by a drawdown on the TGA, which by now has been depleted. We think it is highly unusual for the US to run such large fiscal deficits when the unemployment rate is so low. The Congressional Budget Office projects that social security funds will run out of cash within the next ten years as benefit payments, which have already been above revenues for more than a decade, keep increasing.6

To be clear, the most likely sequencing, in our view, is brinkmanship followed by last-minute or slightly post-‘x-date’ deal. Yields would initially widen due to fear of issuance and credit risk perception, but then rally because the fiscal consolidation has a negative impact in the economy. We think the USD would initially go up, and then sell-off once interest rates declined.

Figure 4: Budget deficit and budget deficit + issuance (% of GDP)

Impact on EM

Sovereign and Corporate debt

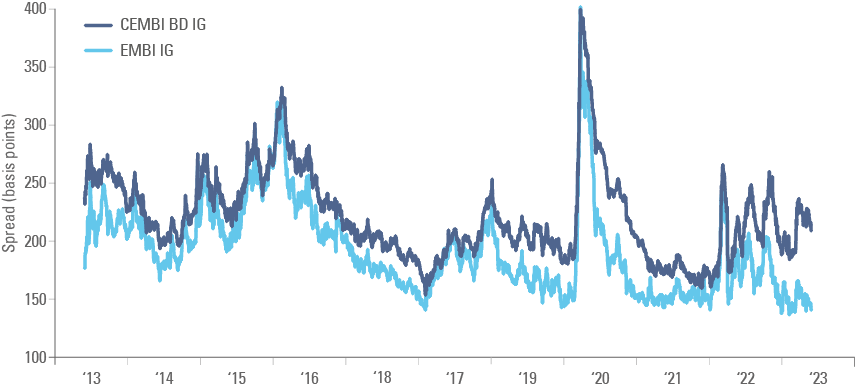

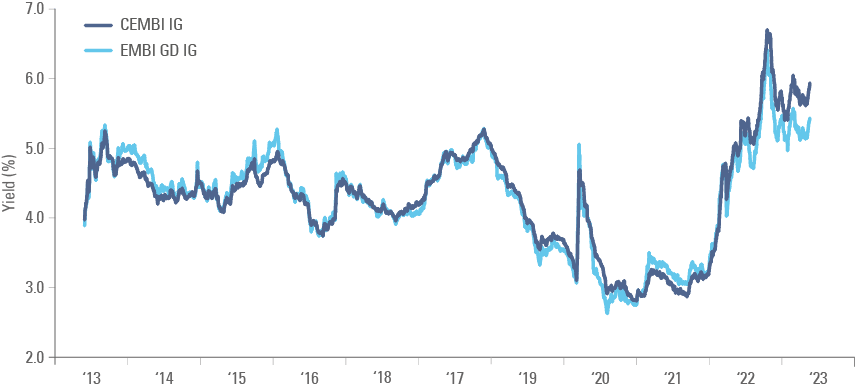

For investors, the debt ceiling end game suggests investment grade (IG) is still your friend. Staying long IG assets and add duration exposure into the short-term volatility is appealing, in our view. Some investors think IG spreads feels “tight” for this point of the cycle (Figure 5). We believe the right way of looking into the asset class is by examining overall yields, which are still close to the highest levels in ten years as per Figure 6.

Fig. 5: EM sovereign and corporate IG spreads

Fig. 6: EM sovereign and corporate IG yield

Within high yield, a barbell between very distressed countries and sound BB-rated credits is preferable over single-Bs. But we are getting close to the point of rotation from IG to the broader part of the asset class. The ‘last flush’ lower in risk assets should come after a significant deterioration in the labour data (negative payrolls) and the Fed properly pivoting to rate cuts.

Local currency debt

Most foreign exchange risk managers and investors are familiar with the ‘Dollar Smile’ model where the USD outperforms both during US recessions or when the US economy outperforms, and typically underperforms when the US economy expands, but at a relatively slower pace than the rest of the world.

A key question we have been increasingly asking ourselves is: Can the Dollar Smile hypothesis break down? In a scenario where a large, front-loaded and poorly conceived fiscal consolidation is forced on the Democratic Party, investors could sell US assets (bonds and stocks), which would bring the Dollar to sell-off. This is unlikely, but possible as illustrated by the UK budget turmoil last year, particularly if the debt ceiling debacle leads investors to lose confidence in the ability of the US to implement a thoughtful fiscal consolidation.

In this scenario, most EM currencies may not be hit as hard, in our view. Most large EM countries have adopted sensible fiscal policies or corrected their excesses, including Indonesia, India and more recently Brazil. EM local bonds are already outperforming year-to-date, thanks to attractive carry and the fact that most central banks are nearing the end of their hiking cycles.

Nevertheless, this very same positive performance year-to-date – alongside fast money positioning – renders EM local currency debt exposed to a small correction. A global recession could make this correction more pronounced. This is not a reason to panic and sell existing exposures, but an opportunity to add into weakness, in our view, since the recession is likely to be driven by an increase in debt servicing costs in the West driving a deterioration in earnings and balance sheets. In our 2023 Outlook, all scenario analysis we ran pointed towards EM local bonds outperforming USD-denominated debt. Strategic long-term investors are taking note.

Summary and Conclusion

The debt ceiling is bringing volatility to market prices. Whilst it is almost impossible to predict whether we will get a deal this weekend, or exactly how it will evolve, the most likely scenario is for an eventual deal to either temporarily suspend the debt ceiling or an agreement where the Democrats are forced to cut expenditures to increase the ceiling, like 2011. In our view, the recent widening in US Treasury yields is an opportunity to add duration exposure on investment grade portfolios, which remains a good place to hide in a turbulent scenario. However, the debt ceiling episode is also bringing question marks regarding the USD status as a global reserve currency, which are farfetched, but resonates into portfolio considering the Dollar expensive valuation. Long term investors are taking note and have been adding exposure to EM local bonds, which have already outperformed Dollar fixed income assets year-to-date.

1. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/05/17/debt-limit-deal-players-00097527

2. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/who-wins-us-debt-default-china

3. https://www.ashmoregroup.com/en-gb/insights/we-wish-all-central-banks-were-steady-as-bank-negara-malaysia and https://www.ashmoregroup.com/en-gb/insights/this-time-was-not-different-the-fed-hiked-until-something-broke

4. https://www.ashmoregroup.com/en-gb/insights/chinas-gdp-growth-beat-expectations-while-us-data-pointed-to-a-recession

5. https://www.ashmoregroup.com/en-gb/insights/we-wish-all-central-banks-were-steady-as-bank-negara-malaysia

6. https://www.crfb.org/papers/analysis-2023-social-security-trustees-report