Chinese property markets are going through a significant slowdown that began in Q2 2021. The average slowdown in the previous episodes over the last 20 years lasted four quarters. The Chinese leadership started to fine-tune macro-prudential policy to the sector in late October, which is likely to support industry consolidation and an eventual stabilisation in asset prices. The big question is: can China engineer a soft landing of its real estate market? In our view, the leadership is already working to this end and will work to avoid large losses for some of the key stakeholders. Chinese leaders are asking property developers’ owners to inject equity to support the operational activity and reduce financial leverage. Furthermore, as the housing market and the economy slow down, the Peoples Bank of China (PBoC) will be in a position to reverse years of tight monetary policy. Therefore, it’s our opinion that the most likely scenario is a consolidation process in the real estate sector over the next quarters allowing for a stabilisation in the sector towards the second half of 2022.

Chinese property state of play

China’s property markets are going through a rough patch. In August 2020, the Chinese leadership implemented a new regulatory measure to curb financial leverage in the property markets, imposing limits across three debt ratios; the three red lines.1 Since the introduction of those limits, most corporate developers have worked to improve their ratios, relatively successful, albeit in some cases this came largely due to lengthening payments to suppliers. The most problematic aspect for developers was the drought in funding conditions as local authorities accelerated the enforcement of the three red lines. The funding drought was mirrored in the credit market by a sudden widening in credit spreads as high yield Chinese bonds (primarily property developers) widened from below 765bps in June to 2,175bps in early November before retracing to 1,609 on 02 December.

At current levels, the bonds of companies with valuable real estate assets, including land and developments under construction, trade at significant discounts compared with recent years. This implies not only defaults, but also large losses after default to bondholders with a very small chance of investor-friendly debt re-profiling deals. Such large losses are unlikely unless Chinese property becomes a systemic risk to broad financial stability.

How will property prices in China evolve? A tale of three cities

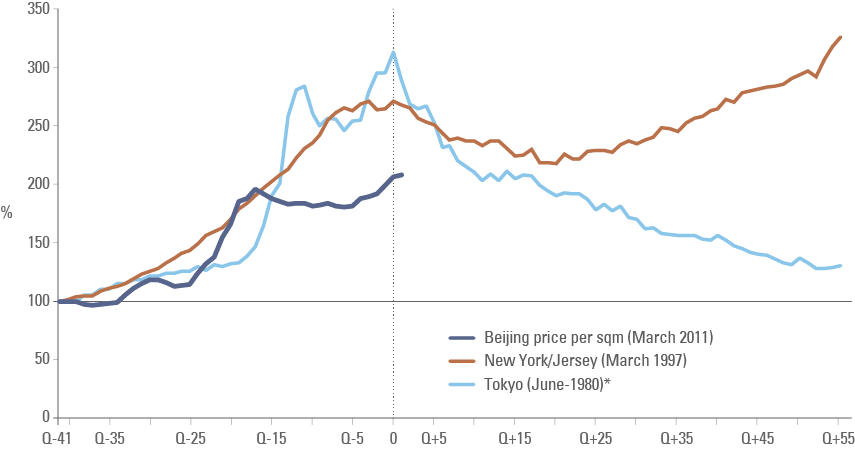

It is easy to jump to conclusions when analysing the Chinese real estate market. Property prices are frothy, particularly in large cities. Financial leverage from property developers is elevated and sales are declining after six years of financial tightening. The key question remains: Will Chinese real estate experience a similar meltdown to the US property market in 2007-2009 or worse, similar to Japanese properties in the 1990s? Figure 1 shows the fate of New York real estate prices after the 2007 crisis was very different than Tokyo’s real estate crisis in 1990. Prices of family houses in New York declined 20% in the five years following the 2007 crisis, but have since recovered and are today at a higher level than during the crisis, whereas in Tokyo house prices declined 58% during the 14years after the crisis and have recovered only 15% since then (not shown in the chart).

Figure 1: Will Beijing follow New York, Tokyo or neither?

China real estate prices do not have to collapse. There are a number of reasons supporting a very different outcome in the situation in China:

- China is in the early stages of a transition from middle-income to high-income status. This journey implies a higher urbanisation rate. Japan had 77% of its population living in cities at the peak of its bubble in 1990, the US was 80% urbanisation in 2007. In comparison, China had 56% of its population living in cities in 2015 and 64% according to the latest census in 2020, up from 36% in 2000 and 50% in 2010. These are still very low rates of urban population. Mongolia’s urbanisation rate, for example, stands at 68% and Brazil at 86%. If the urbanisation rate reaches 84% in China, approximately 300m individuals will move to cities, which means the demand for houses in cities is likely to remain elevated over the coming decades.

- China’s GDP per capita has increased to USD 16.4k in 2021, crossing the World’s average (USD 16.2k) for the first time. In comparison, Japan had USD 32.5k GDP per capita in 1990 (USD 42k in 2020) and the US had USD 56k GDP per capita in 2007 (USD 60k in 2020). GDP per capita growth is supported by an extraordinary 8.4% p.a. increase in labour productivity since 1990 (versus 2.0% p.a. in the United States). High levels of education and continuous urbanisation is likely to keep productivity growth at very high levels, even if it slows down from here. In other words, China still has a lot of room to boost its GDP per capita aiming to achieve high-income status, which is likely to lead to more demand for real estate as urbanisation rates increase.2

- China’s ascendance to high-income is possible by the development of native cutting-edge technology across a number of sectors. Technological convergence will demand a larger percentage of its population achieving (already best in class) high educational levels, which means productivity growth is sustainable. This will increase demand for property, in particular around the high technology urban areas such as the Greater Bay Area.

- Real estate ownership in China is high for cultural and economic reasons. Several years of one-child policy led to an imbalance in the ratio of men to woman in China. Single male individuals willing to start a family are expected to provide a place to live in a prestigious city. The high saving rates across older individuals means that parents often support their children’s property purchases. Furthermore, small business owners often use property as a saving vehicle. The property can be a useful guarantee to raise loans for their companies with banks, which are wary of lending money to small business without guarantees. Lastly, Chinese savers have few alternatives to invest capital, with bank deposits, real estate and equities being the most traditional asset classes. Chinese savers preference for real estate is evident as bank deposits offer low real interest rates and equities have historically displayed a high degree of volatility. Housing accounts for as much as 65% of the total household assets according to the IMF.

Focus on an orderly industry de-leverage

The crackdown on the real estate market is a signal that the leadership will not allow overly leveraged business models to perpetuate. The main shareholders of property developing companies have been asked to recapitalise their businesses to support ongoing delivery of pre-sold properties as well as financial de-leverage.

While the Chinese leadership may force a change of control at the helm of the profligate companies, it is highly likely that the regulators will be wary of causing too much pain for the companies that funded the vast majority of liabilities in the sector – suppliers and banks. Local governments have ring-fenced the operational companies precisely to ensure that suppliers and employees are paid to keep building existing projects so that the final client receives what they have purchased.

Last weekend, the The PBoC, the CBIRC and the MHURD issued concomitant statements saying the Evergrande crisis was a result of the company’s poor management and the spillover effect was manageable given financial liabilities accounted for about one-third of the firm’s total debt, and the delivery of ongoing projects is ensured.3 The CBIRC also stated its intention to support demand for both first homes and housing upgrades (second homes), the first time in six years that Beijing has signaled support for second-house demand. Banks and bondholders (both local and foreign) will welcome debt re-profile exercises from companies with liquidity problems, as long as they are conducted in a fair, transparent and candid manner.

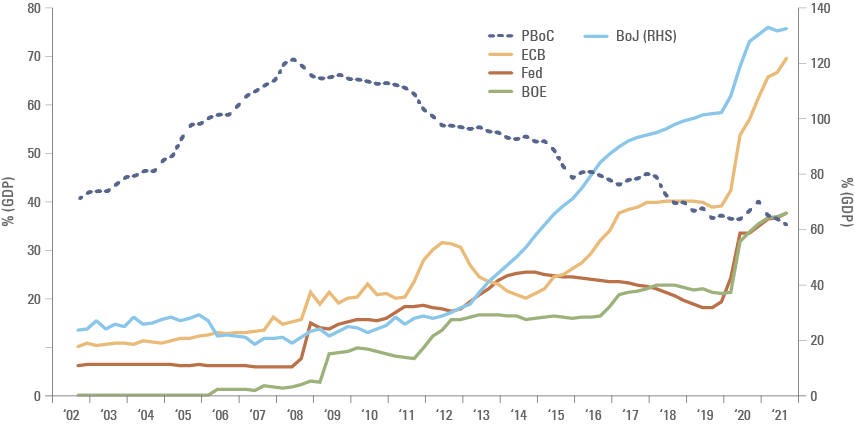

The deleveraging effort is not new. Figure 2 illustrates that the PBoC had started an aggressive quantitative tightening - expanding its balance sheet at a much slower pace than its economy – particularly from 2015. From March 2002 to March 2008 the PBoC expanded its balance sheet at a 25.3% per annum (pa) slowing to 9.4% pa in the following seven years before slamming the brakes on to a meagre 2.2% pa expansion since March 2015. The period of quantitative tightening since mid-2015 was accompanied by tightening measures specific to property markets and coincided with the pre-covid peak in Beijing house prices illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 2: PBoC balance sheet in CNY

In fact, the PBoC has been the only contrarian central bank reducing the size of its balance sheet as a percentage of its economy since 2008, precisely when global central banks embraced huge programmes of quantitative easing as per figure 3, leading to massive distortions in global capital markets. Furthermore, the PBoC main policy rates are far from the zero lower bound and it has never considered lowering policy rates to negative levels. That renders China the only large economy in the world with a large monetary bazooka in its hand.

Figure 3: Global Central Banks Balance Sheet (% of GDP)

The path of correction

Over the next quarters, the PBoC is likely to ease macro prudential rules for the property sector, for example, allowing developers who are willing to buy assets from troubled developers to temporarily breach some of the three red lines. This would allow well managed companies to acquire valuable assets from weaker ones, avoiding a messier liquidation of assets and allowing for a normalisation of sales of new buildings. The PBoC is also adding support for small businesses, cutting the reserve requirement ratio so banks can lend more to small companies.

Over the long term, it appears that China will actively promote a policy to lower the cost of living. This implies that either salaries will increase or the prices of renting and buying a property will decline – or a combination of higher salaries and lower housing costs. Thanks to high productivity growth, China can afford to increase wages at a relatively fast pace, which means that housing prices remaining unchanged would suffice to improve house affordability for the population.

Conclusion

After six years of monetary policy tightening and macro-prudential rules restricting real estate acquisitions, the Chinese property market has experienced a significant slowdown. However, the value of real estate assets do not need to collapse as it did in Japan. China’s urbanisation rate and GDP per capita remain relatively low, which means demand for property is likely to rise as the country develops from a middle-income to high-income economy.

In the short term, the PBoC and other regulators are likely to oversee a balanced soft-landing of the sector, as badly managed companies are ring-fenced by local governments while they re-profile their liabilities. Furthermore, authorities have started easing monetary policy and macro-prudential rules, which should allow for higher demand for real estate and consolidation in the sector. Therefore, in our view the real estate market is likely to stabilise during 2022, without major long-term implications for Chinese development.

1. The three red lines are:

- 1) Total liabilities/Total assets (ex-customer deposits or advances) < 70%

- 2) Net debt/Total equity < 100%

- 3) Total cash/Short term debt > 1.0.

3. CBIRC: China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission; MHURD: Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development