China’s new development strategy: greener, less unequal, more sustainable

The country’s leadership has designed a new development model, based on a ‘common prosperity’ philosophy, aimed at modernising the economy by improving the country’s future demographic profile via lowering inequality and promoting sustainable, even if slower, GDP growth which is both less dependent on financial leverage and in harmony with nature.

Over the last decades, China has relentlessly reformed the structure of its economy in pursuit of economic growth, allowing the country to become the second largest economy in the world in a relatively short period.

In our view, the leadership will manage to transition its development model to a modern, sustainable and less unequal one, despite the delicate balancing acts of deleveraging the economy and designing regulations designed to achieve its objectives.

A new development model

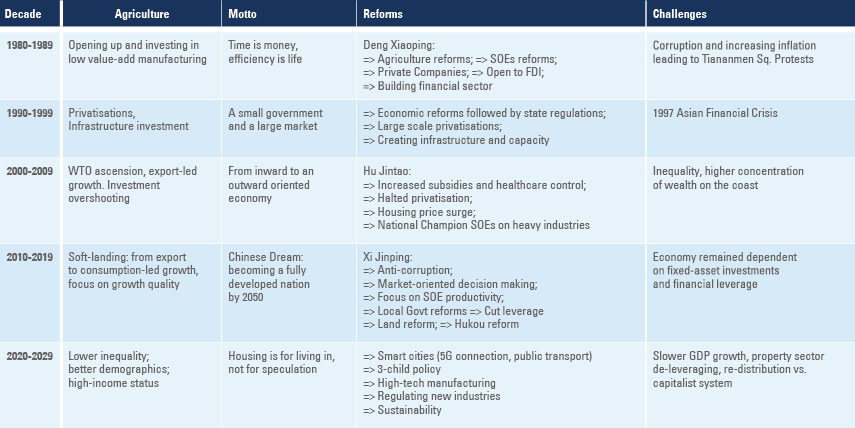

China’s achievements over the last four decades have been, in one word, extraordinary. A relentless effort to reform its economic growth strategies has allowed for a compounded annual gross rate of GDP growth close to 10% from 1980 to 2020, resulting in an expansion of its GDP from USD 0.3bn in 1980 to USD 14.7tn in 2020. The road to success was paved with the removal of political obstacles to implement challenging structural reforms, which often seemed unattainable. In most circumstances, the Chinese leadership has adjusted its development strategy in a thoughtful manner.

All structural reforms pose political challenges, but most recent Chinese leaders did not shy away from adjusting as per Figure 1. In the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping wrestled against vested interests to implement broad agriculture and state-owned enterprise (SOE) reforms as well as opening China to foreign direct investment (FDI) and building the country’s financial sector.

In the 1990s China focused on reforms allowing for its ascension to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), undertook large scale privatisations, invested heavily in infrastructure to boost production capacity and restructured its financial system by recapitalising banks and reducing non-performing loans. Thanks to these reforms, China navigated the Asian crisis of 1997-1999 relatively well.

In the 2000s, China took advantage of its favourable competitive position in terms of abundant availability of labour and capital channelled via a lean financial system to create an infrastructure and export-led growth boom on a scale never seen before.

On the negative side, Hu Jintao encouraged large SOEs to become national champions as he halted privatisation in favour of state control, resulting in a large increase in inequality. Over the last decade, Xi Jinping has been trying to address the excesses engaging in an anti-corruption crusade which resulted in higher local governments and SOE productivity. Xi Jinping also implemented important reforms such as land reform and the immigration system (Hukou) reform, allowing for a faster urbanisation pace.

Fig 1: China’s economic development journey

Table 2

The relentless path of expansion had collateral effects, including oversupply and excessive leverage in a few industries. China has the ability to address these issues, as the economy is large and diversified enough to absorb shocks, and the funding for the liabilities accumulated by households, local governments and corporate sectors is denominated in local currency and largely provided by Chinese savings deposited in local banks. The current government has been working to address the oversupply in a number of sectors and is now pushing for more credit differentiation by keeping monetary and fiscal policy tight and not bailing out ‘unsystemic’ state-owned companies and large corporations that have relied on moral hazard to increase financial leverage.

In spite of the challenges, China has its eyes on the long-term. The leadership has committed to a new development philosophy of common prosperity anchored on sustainable growth from both financial and environmental perspectives as well as lowering inequality. One of the key objectives of the policies is to boost the country’s fertility rate to improve the country’s future demographic profile, creating the basis for a self-sustainable economic model. Another implicit objective, in our view, is to escape the ‘secular stagnation’ fate faced by most developed markets (DM). Boosting quality of life demands improving the living conditions across the population, which also entails adjusting income and wealth inequality.

Common prosperity does not mean China is giving up on capitalism. The capitalist system is anchored in the idea that individuals act in accordance with their interests, allowing for market forces to maximise the reward of good economic bets via capital gains, while bad bets leads to capital losses. President Xi Jinping made clear in numerous speeches that the China Communist Party believes the private sector is more efficient at allocating capital. The main difference is that China sees a role for the public sector in guiding and supporting the private sector to industries that will allow the country to develop its core strategic goals.

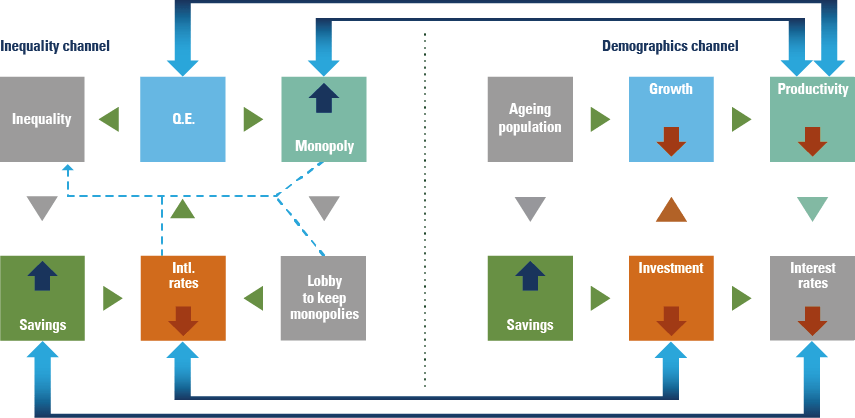

1 | Improving demographic profile

A number of developed market economies, including Japan, Europe and increasingly the United States have been ‘stuck’ in an uncomfortable ‘secular stagnation’ dynamic where the natural (real) interest rate that balances supply and demand stands significantly below 0% – the lower bound of traditional central banks’ monetary policy tools. Two of the key culprits for secular stagnation are higher inequality and deteriorating demographics. These two long-term dynamics lead to lower GDP growth, forcing the government to boost expenditures, leading to both higher debt levels and lower productivity (as public sector investment is often less productive than private sector), which demands permanently lower interest rates. The demographics and inequality vicious cycles are intertwined in self-reinforcing dynamics depicted in the flow chart on Appendix 1.

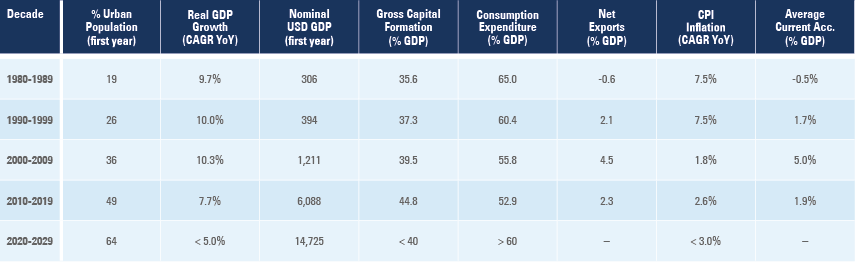

Figure 2 shows that China’s demographic sweet spot of age-dependency ratio (below 50) started in 1994 and will end approximately in 2030. From that point, China’s demographic profile will deteriorate with its age-dependency ratio deteriorating beyond the US by early 2040. In order to avoid such a rapid deterioration, China is motivating families to have more offspring, by moving from a one-child policy to a three-child policy.

Fig 2: Age dependency ratio: China and selected countries

2 | Reducing inequality to improve demographics: tackling the ‘three big mountains’

No country in the modern world helped lift so many families above the poverty line than China. The deep trading partnerships established with EM countries over the last decades alongside strategic investment across Central Asia, Middle East and Africa (Belt & Road initiative) boosted global economic activity across EM, creating millions of jobs in the process. Furthermore, China’s economic growth allowed for hundreds of millions of Chinese individuals to rise above the poverty zone. Globally, billions of people emerged from the poverty line, thanks to China.

In its next stage of development, China is looking to address its demographic challenge by moving from a one-child policy to a three-child policy. The main factor leading to lower birth rates across the world is economical. About one hundred years ago, newly born children represented a net positive cash flow to the family, as they would start working at a young age in farming or other activities. Today children make a big hole in most family’s budgets.

Therefore, in order to boost birth rates, the leadership is focusing on reducing the cost of housing, education and healthcare – the ‘three big mountains’ standing in the way of middle class development. Flattening the three big mountains is only possible with government guidance and regulatory actions; some of it caused volatility in the equity and some parts of the credit markets.

On the other hand, better education, healthcare and living standards (housing) should also lead to higher productivity. Over the long term, a richer population that is less concerned about healthcare and education costs will naturally increase consumption, supporting the current economic transition. On a global scale, higher wages in China are likely to remove downward pressure from low value-add manufacturing jobs across DM and motivate further investment in manufacturing in frontier economies, both contributing towards less global inequality. The main unintended risk is higher global inflation.

In order to achieve its objective, China is likely to focus on a number of actions, such as introducing more progressive taxation, promoting charity and supporting sustainable business practices (by taxing unsustainable ones). Higher revenues and newly available technology should allow for a higher level of education for all children and funding a more comprehensive healthcare safety net.

Sustainable growth

1 | Lowering financial leverage

Xi Jinping has been advocating for lower financial leverage since the beginning of his administration. However, this objective conflicted with the goal of doubling the size of the economy from 2010 to 2020 ahead of the in the 100th anniversary of the CCP in 2021. Furthermore, reducing financial leverage implies reducing the pace of GDP growth and the size of some specific industries, which is not straightforward from a political perspective. Despite the challenges, the government has taken several steps in this direction. Over the past eighteen months, China has been supporting better capital allocation by allowing more debt restructurings from high yield issuers that have not adjusted their balance sheets. Since August 2020, the Chinese leadership is explicitly demanding property developers to cut gearing via the three red lines, which imposes limits across the debt-to-cash, debt-to-assets and debt-to-equity ratios.

The government objective is to engineer a ‘soft-landing’ deleverage to lower systemic risks. A collapse of property developers would slow down the pace of Chinese urbanisation, an important source of economic and productivity growth. The housing sector has been operating like a quasi-utility industry for a number of years as local governments regulate the price of land and the government now has a heavy hand in sales prices as well. In their deleveraging effort, for example, local governments are discouraging property developers to sell real estate assets at deep discounts in order to preserve the market integrity.

The ongoing Evergrande situation is a clear signal that the government will not allow highly leveraged business models to perpetuate. Evergrande and other property developers have made good progress in lowering its financial ratios to comply with the three red lines. However, they have remained exposed to liquidity risk as sales of property slowdown and credit conditions remained tight, both for developers and for final buyers.

The transition to a less leveraged property market will be a delicate one. Beijing will have to cut a fine balance between punishing bad stakeholders and avoiding a systemic risk. The good news is that the authorities are well aware of the risks and have the tools to deal with the situation, in our view. More recently, Evergrande has been progressing in selling assets, cutting down costs and closing loss-making businesses. We believe an orderly debt re-profiling is the most likely scenario.

Banks are well capitalised and in a good position to support companies in their efforts to re-profile their liabilities, if necessary. Local governments can support a smooth operation of subsidiaries from over-indebted holding companies. The Central Bank can ease financial liquidity for house ownership as well as for the broader banking sector. The central government can boost fiscal expenditures and allow local governments to front-load their debt issuance plans, should revenue from land sales continue to decline. Finally, the government can promote investments in affordable housing and infrastructure. For example, China built 78 million affordable houses over the last 13 years and the State Council pledged to build 930k affordable rental housing units in 40 pilot cities in 2021. During the 14th five-year plan from 2021 to 2025, the government estimates that affordable rental housing units should reach 30% of all new residential homes supplied in cities attracting young migrants.

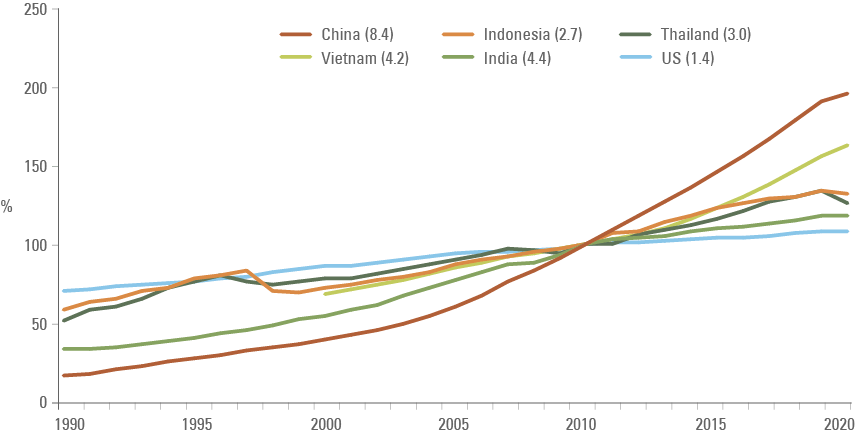

2 | Boosting productivity: The fifth stage of economic development

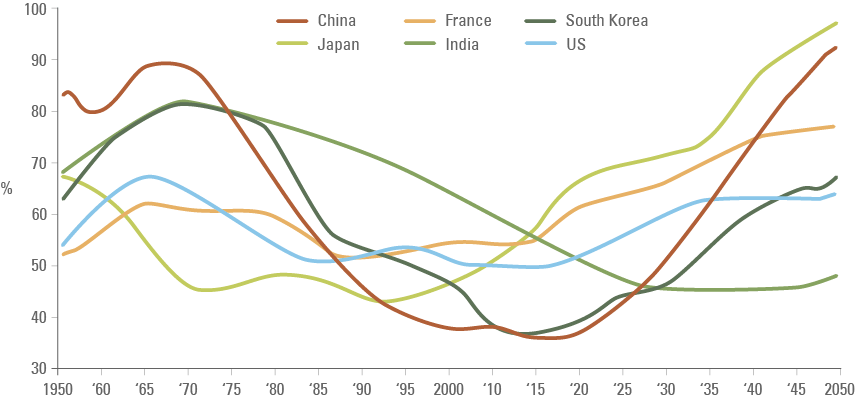

China was only able to achieve the impressive high growth profile over the last decades due to fast productivity growth as illustrated in Figure 3. China’s productivity is fully related to its solid educational system, both basic and higher education. China punches well above its weight in terms of educational levels, outperforming countries with a much larger GDP per capita. China currently graduated 1.38 million engineers* in 2020, according to data from Statista.1 China graduates nearly 10x more engineers per year than the US.2 In addition, China graduates 50k STEM PhD’s on an annual basis, compared with 34k in the US.3

Fig 3: China productivity vs. selected countries

Reflecting its academic prowess, China filed 1.3 million patent applications in 2019, dwarfing the US (521k) and Japan (452k).4 It is not surprising that China already leads the development efforts across a number of important industries. The country has the largest number of internet users in the world, with 989 million active users in December 2020 from 904 million in March 2020, as the pandemic led to an acceleration of the adoption of the internet. China is also the leading country in e-commerce with 782 million individuals shopping online, thanks to its state-of-the-art online payment systems fully integrated with social media platforms.

The country is also a leader in Central Bank digital currencies, adopting digital cash with an expiry date to provide targeted stimulus support during the pandemic. Finally, in the software space, China is a key competitor in the development of artificial intelligence. In the hardware space, the country leads efforts in key strategic areas such as quantum computing, the fifth generation of broadband and drones. China is also the leading manufacturer of wind turbines and equipment as well as solar panels and integrated systems. China is already the largest producer of electric vehicles (EVs) in the world, responsible for nearly 50% of all cars produced over the last decade.5,6

Furthermore, the government is actively promoting investments into the frontier of science and economic development including:

- Reaching high-technology supply-chain self-sufficiency by catching up in high-specification semi-conductor production and development.

- Leading the Electric Vehicles revolution, including autonomous drive and battery technology improvements.

- Boosting China’s participation in strategic industries such as wide-body aircraft and life sciences.

- Investing in smart cities, connected with 5G broadband, which allows for improved and automated services such as public transport.

- Innovation:

- China productivity has a lot of room to improve via technology diffusion. China can, for example, create industry associations and invest in lifelong learning in order to create the conditions for technological catch up between less productive small and medium enterprises to large companies.

- China will also absorb more technology from abroad by implementing reforms that opens up its borders for investment and production.

- The State Council recently issued a guideline on intellectual property (IP) development and protection for the period 2021 to 2035. The guideline seeks to boost compensation for losses resulting from violations, pushes for negotiations on IP-related issues with other countries and guides IP protection in new economy and internet-related areas, addressing a key conflict with the US

- China can promote more innovation by tax cuts, subsidies and direct grants

- Promote further trade and investment deals

- Level the playing field between SOEs and private sector.

3 | Regulation

Most of the regulatory measures taken by China are thoughtful, in our view. The objective on the regulatory drive across industries are three-fold: (1) tackle monopolies; (2) end predatory practices; and (3) share the benefits of technology across society.

a) E-commerce and big-tech

Big data companies should share their insights with the government in order to allow for better social policies and sustainable development. We believe that higher regulatory pressures on the technology sector in the name of less inequality and lowering the risks of predatory practices were overdue on a global scale. China is ahead of the game taking a proactive stance and thoughtfully regulating these new industries, which may lead to long-term opportunities.

In fact, this is an area where China’s interests align with the West. The European and United States governments have been working to regulate new businesses that compete with traditional sectors on unfair terms. For example, the new technology media (i.e. Google, Facebook, Baidu, etc.) face a much lower regulatory burden than traditional media (i.e. newspapers and television). Therefore, China is leading the transition to more sustainable regulatory practices, in our view.

b) Fintech

Financial technology (Fintech) firms have used big data to support lending decisions representing USD 500bn in 2019 from USD 9bn in 2015 according to the Bank of International Settlements (BIS). At the same time, Fintech companies were warehousing very little credit risk in their balance sheet, as they sold the vast majority of their loans to small business and individuals to big banks. This was creating an incentive structure for negligent generation of new loans, in a similar dynamic to the structured derivatives that allowed for the twin housing and financial sector crisis of 2007-08. By curbing bad practices early, China is trying to make sure that financial innovation does not lead to financial instability.

Furthermore, China has working to overhaul its data protection legislative framework. In 2017 the country passed its cybersecurity law and in June 2021 the country approved its version of data and personal information security law, with similar impact to the regulations implemented in Europe, a positive development protecting internet users.

c) Anti-trust

Competition is a key element of any healthy capitalist system. In some historical circumstances, innovators or companies that adopt of new technologies in business savvy ways can create monopolies. Striving to innovate is positive for the economy and society. However, companies will do all they can to maintain monopolistic positions, to benefit from larger profit margins and market control. Thoughtful regulations will avoid companies abusing monopolistic position and incentivise competition.

A few giants dominate the Chinese internet industry. In e-commerce, the three largest players control more than 80% of the market share against slightly more than 50% in the US. China is now forcing e-commerce platforms to end discriminatory practices such as prohibiting vendors that are listed on competitors’ websites to be part of their platform which will benefit small businesses and merchants, by allowing them to list their products in multiple websites.7

In the food delivery industry, the top two players controls almost 100% of the market while the top-two ride-hailing companies have more than 90% of market share (Didi 85%). Such concentrated market share could lead to practices that preserve their monopolistic position. These companies are also accumulating a wealth of data, which could be very useful for public policy. Furthermore, both food delivery and ride-railing companies have a very poor record of accomplishment on the social side, granting little-to-no employee rights and creating incentives for workers to over-extend their hours beyond healthy times, creating stress and hazard risks.

d) Cryptocurrencies

At its peak, China was responsible for mining 76% of all crypto mining. This is despite the fact that mining crypto requires energy, which in the case of China comes mostly from coal power plants; leading to significant carbon emissions whilst no value is added to the real world economy, dominate its energy matrix. Over the last year, China banned the mining of crypto within its territory and prohibited companies to provide cryptocurrency access to Chinese individuals due to concerns over money laundering, financial security and graft.

e) Education

The Ministry of Education surveyed around 19k education firms, 700k children and over 150k parents before issuing regulations that banned foreign direct investment and for-profit investments in education. In our view, China wants to avoid the creation of inequality machines – schools and universities that charge a much higher price (or influence) to become part of their alumni. Instead, it will use technology to bring a high level of education to the majority of its population, boosting meritocracy.

f) Virtual games

The gaming industry ought to limit the amount of time that children, teenager and even young adults spend in front of the screen – any sensible parent or industry expert would agree with this view.

g) Healthcare

We believe the third mountain, the healthcare sector, is ripe for regulatory actions, particularly in the segments adopting predatory practices (i.e. plastic surgery) or that use big-data to carve out monopolies.

h) The upside in regulatory measures

Regulation is always bad news in the short-term for investors. Higher level of uncertainty leads to an increased risk-premium on stock valuations, which translates into lower net present value for the same stream of expected future cash flow. At the same time, the profitability of entire industries can be affected by lower margins as a result of regulatory actions that raises companies’ costs.

In our view, the short-term negative impacts were largely incorporated in market valuations over the last 12-months since the cancelation of the IPO of Ant Group – the payment company of Ali Baba. However, the medium to long-term impact of the measures are still unclear. If China is successful in its next phase of development, lower inequality and higher productivity will create a larger and richer middle class, boosting the potential market for the very same players that are suffering from the tougher regulatory regime today. After a more sustainable regulatory balance is achieved, companies and can re-focus on their business.

A good analogy would be Henry Ford’s revolution, roughly one-hundred years ago, of doubling the average wages to his employees while cutting car prices allowing for more stable and productive workforce that would also become consumers of its product. A strategy that compressed margins, but significantly expanded the potential market, generating a virtuous cycle in the auto industry.

i) Risks

As always, the main risk from regulatory actions is that they stifle the more dynamic allocation of resources from the private sector, lowering the ability of the country to innovate leading to lower productivity. A number of senior leaders from the politburo have continuously evoked the importance of private sector allocation of resources. Therefore, we believe the authorities will be careful not to reduce the incentives for the private sector when implementing regulations. The recent overhaul of the intellectual property issued by the State Council is a good example of regulations that would lead to more investment in innovation, not less.

4 | Environment

China is returning to its philosophical roots. Taoism, one of the three major Chinese philosophies entails to keep human behaviour in accordance with the alternating cycles of nature and non-interference with the course of natural events. By focusing on sustainable forms of production and energy generation in order to preserve the natural environment China has the potential to lead the path to a world with net-zero emission of greenhouse gases.

Environmental concerns is another area where China’s interests and actions fully converge with Europe and now the US. China has pledged to cuts its net emissions to zero by 2060, a herculean effort as the leading manufacturing country in the world still depends on coal thermoelectric power plants to generate approximately 60% of its energy. According to the International Energy Agency, “China will account for more than 40% of global renewable capacity expansion between 2019 and 2024, driven by improved system integration, lower curtailment rates and enhanced competitiveness of both solar PV and onshore wind”. More recently, Xi Jinping promised not to fund the construction of any new coal power plants overseas, finding common ground with the US administration.

When analysing CO2 emissions on a consumption-basis and CO2 per capita versus GDP per capita, China’s emission profile is similar to Eastern Europe, and better than the US. Therefore, it is clear that a good part of the country’s emissions profile is due to the sheer size of its economy and the largest population in the world.8

China excels in many areas when it comes to environmental concerns. The country has been the leading the increase in the manufacturing capacity of key renewable energy sources such as solar, wind and hydroelectric power. Furthermore, over the last five years or so, the government has been actively trying to reduce the pollution levels across its largest cities, in order to allow for better live quality. More recently, the government has encouraged energy and resource intensive industries like steel and aluminium to improve its processes as well as shutting down large pollutant industries such as cryptocurrencies.

5 | Foreign policy

The risk of a sharp deterioration in the China-US relationships is subsiding after the election of Joe Biden. The relationship between China and the new US administration got off to a rocky start during first meeting between Anthony Blinken and Wang Yi where the US foreign minister unusually angled aggressive comments to please the US population.

More recently, Presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping spoke over the telephone and the US President committed to find a more balanced competitive position. Biden had a good relationship with Xi Jinping during the Obama administration years and is likely to try to heal the damage caused by the previous government. China confirmed there were areas where the two countries can cooperate (i.e. climate change), but the US has to stop undermining the country’s technological development and Trump-era tariffs are still in place.

Having said that, China’s image in the eyes of the US population was severely damaged by Trump’s attacks as well as the pro-democratic protests in Hong Kong and the origins of the Covid-19 virus. China retaliated in its own local media, creating a deep polarisation between the two country’s populations. Over the medium to long term, the two countries will have to find common ground on a number of strategic areas where their interests oppose, including technological development, South China Sea dominance, North Korea and Taiwan. Therefore, tensions between the two largest super-powers in the world is likely to generate negative headlines and volatility, which generates opportunities for active managers.

China’s new development model will also have long-term implications for foreign policy. One of the key objectives of the new strategy is to lower China’s dependency from external markets, which means boosting consumption and achieving technological and natural resources self-sufficiency. China will weigh its heavy economic and political influence to achieve these objectives.

Summary and conclusion

China’s leadership designed a new development model, based at ‘common prosperity’ philosophy, aimed at modernising the economy by improving the country’s future demographic profile via lowering inequality and promoting sustainable, even if slower, GDP growth which is both less dependent on financial leverage and in harmony with nature.

Over the last decades, China has relentlessly reformed the structure of its economy in pursuit of economic growth, allowing the country to become the second largest economy in the world in a relatively short period.

In our view, the leadership will manage to transition its development model to a modern, sustainable and less unequal one, despite the delicate balancing acts of deleveraging the economy and designing regulations designed to achieve its objectives.

Appendix

Secular stagnation reinforcing vicious cycle

Higher inequality means a larger share of the disposable income flows to rich individuals with a lower propensity to spend, leading to higher saving rates and less consumption across the economy. Lower consumption leads to a drop in demand for goods and services and lower investments, both leading to lower nominal economic growth, which drives real interest rates to a structurally lower level. Higher government expenditure often follows, but inefficient allocations leads to a lower GDP growth than the fiscal expenditure (low GDP multiplier), resulting in higher public debt, which further depresses interest rates.

As the natural interest rate of equilibrium drops below zero, central banks have to resort to negative interest rate policies (NIRP) and large asset purchasing programmes (quantitative easing, or QE). Such policies lower the discount rate for any cash-flow positive asset, leading to a boom in asset prices, mostly controlled by the rich, exacerbating inequality. Furthermore, access to capital at extremely cheap levels allowed the wealthier part of the population to invest in new industries, including technologies, which were responsible for the disruption of important traditional sectors – monopolies fiercely defended in democratic countries via an army of lobbyists. When responding to the Covid-19 pandemic with unprecedented stimulus, western economies contributed to a vast exacerbation of inequality.

The second channel, demographics, is also believed to motivate secular stagnation, as ageing populations have a higher propensity to save more and lower propensity to invest in productive activities. Ageing populations also demand more healthcare products and services and fewer items that tends to generate a broader economic boost. For example, young adults tends to have more propensity to spend their earnings on housing and cars, products involving deep supply chains and often leads to higher demand across other industries like furniture, repairs and other services. Furthermore, when the overall population ages due to a decline in fertility rates, a smaller share of economically active individuals have to provide for a larger share of inactive population (elderly and children). Both factors leads to higher saving rates, less investments, declining productivity and lower economic growth, driving interest rates lower.9,10

Fig 4: China is working to escape secular stagnation

1. See https://www.statista.com/statistics/610751/china-engineering-undergraduate-graduates/

* The category of engineering in the Chinese education system is comparatively broad and includes instrumentation, energy and power, computer science and technology, electronic information science and technology, software engineering, electrical information, transportation, ocean engineering, light industry, textile, aerospace, mechanics, biological engineering, agricultural engineering, forestry engineering, public security technology, plant production, geology and minerals, materials, machinery, food, weapons, civil engineering, water conservancy, surveying and mapping, environment and safety, and chemical and pharmaceutical engineering.

4. See https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_941_2020.pdf

5. See https://theicct.org/publications/us-position-global-ev-jun2021

6. See https://www.ft.com/video/4a0a55cd-b21d-4ae4-be4d-1cf92b50b6ba

7. See https://multimedia.scmp.com/infographics/china-internet-2021/

8. See “Seven policy proposals to meet the Paris Agreement objectives”, The Emerging View, 13 April 2021.

9. Having said that, some economists put forward an important thesis suggesting demographics will become an inflationary force over the next decades, while other recent studies have suggested that, at least in the US economy, inequality was a much more important factor for secular stagnation in the United States than demographics.

10. See https://www.kansascityfed.org/documents/8337/JH_paper_Sufi_3.pdf