The most interesting investment opportunity in 2024 is also the most controversial. Investing in Argentinian assets could deliver extraordinary returns, if Milei manages to implement his most essential economic reforms. However, even optimistic economists and analysts struggle to see an open path for these economic reforms to work. This paper does so, proposing the ideal reform sequence, by which Argentina can regain the economic dynamism it displayed in the late 19th Century.

Milei, with the support of Sturzenegger and Caputo is now engaging on Act I, restoring economic competitiveness, balancing fiscal accounts and re-profiling a mountain of short-term debt. This act will be the most difficult to pull off, as it directly challenges the establishment – the Unions and Peronists who have held power for nearly 75 years.

Act II will be simpler, involving a monetary stabilization plan, through which Argentina should benefit from a triple inflow of Dollars from exporters, foreign and local investors.

The third act will be the notorious dollarisation. This will be the least crucial but most controversial of the reforms, in our view, and may become the theme of many Tangos in the future.

Por Una Cabeza by Carlos Gardel and Alfredo Le Pera is a masterwork tango where a bohemian poetically intertwines his addiction to horse-racing gambling and his passion for beautiful women.1 Gardel, a Frenchborn Argentinian, was born in 1890 when Argentina was roaring with confidence and power, buoyed by conservative governments from 1870 to 1914, and attracting a large amount of British investments in railways (and other activities) in the 1880s. This foreign investment helped make the Pampas one of the most productive agriculture export platforms in the world. During the last three decades of the 19th Century, Argentina outgrew Australia and Canada in population and per capita income.2 However, this prosperity was ultimately transient. Gardel and Pera wrote Por Una Cabeza in 1935, the same year when a tragic crash between two Ford Trimotor airplanes took their lives in Medellin. The sophisticated but decadent tone of the song resembles the economy of Argentina over the same period – a shiny exterior – but rotten core in the aftermath of the First World War when the British economy became dependent on the US and stopped exporting capital, before the 1929 Wall Street Crash.

During his speech in Davos, President Javier Milei recollected how Argentina became a powerhouse of growth in the late 19th Century, by embracing liberal ideals and free markets. The discourse was a clever way to promote his ultra-liberal philosophy to the rest of the world, in contrast to a stark warning that the West is becoming bogged down by the kind of socialist principles that stifle growth. A proud follower of the school of Austrian Economics, Milei condemned state intervention as representative of impoverishing socialism. He is right and wrong at the same time, in our view. The illusion that markets will function perfectly without any checks and balances has been repeatedly dismissed in the past, most famously after the 1930 Great Depression by Lord John Maynard Keynes. However, Milei is right about the fact that the West has long been engaging in too much state intervention. This has led to bloated state expenditures and higher debt ratios, which at some point will have to be serviced via taxation. State intervention should, by definition, be minimal. Too much of it causes a ‘crowding out effect,’ which not only makes it more difficult for the more efficient private sector to invest. The state should, instead, focus on creating an environment that fosters competition, both within and across industries. Milei’s Davos address ended with a cry for all world capitalists to come and invest in a new liberal beacon, Argentina. Can Milei’s dream come true?

This article outlines a strategic roadmap for Milei to effectively realise his ambitious goals for Argentina. There are three stages for a sustainable programme to stabilise the economy.

- Act 1 - Fixing Economic Imbalances; Fiscal Adjustment; and Reprofiling Local Debt

- Act 2 - Monetary Stabilisation Plan

- Act 3 - Dollarisation

Today, we are in the early to middle stage of Act 1. It goes without saying that this is a road riddled with uncertainties and social stress, but we believe there is a higher likelihood they succeed than markets currently expect. The result would also be very positive for working Argentinians, in our view.

It Takes Two to Tango

Most investors feared Javier Milei coming to power. Not necessarily because of his ideas, but because they didn’t see a path towards implementing them in a country as politically complicated as Argentina. The influence of unions has loomed large since the 1930’s and became a vital part of the system when Juan Perón came to power in 1946. This bloated system led to three-quarters of a century of chronic over expenditure, defaults, and inflation cycles. No wonder Milei’s “less government” plan sounded like a good bet to Argentina’s tired electorate.

So, the big surprise wasn’t really the election of Javier Milei, but how quickly he has turned towards pragmatism to govern. Milei appointed various ministers from former president Mauricio Macri’s Juntos Por Cambio (JxC), including his challenger presidential candidate Patricia Bullrich as minister of security. JxC brings politicians with a similar vision for Argentina and importantly, Congress votes. While the Peronist parties still control slightly less than 50% of Congress, Milei’s La Liberdad Avanza Party alongside JxC and two other smaller parties have a simple majority in the Lower House and the Senate.

Milei, so far, has proposed two key pieces of legislation. On 20 December, he put forward an Emergency Decree to establish the “Foundations for the Reconstruction of Argentina’s Economy” with 366 items, which have been valid (except for the labour components) since 29 December. These will remain valid unless the Supreme Court declares it null.3

The second piece was an ‘omnibus’ bill, with more than 600 items. This bill was renegotiated and approved by the Congress Commission last week. However, over the weekend the government has opted to remove the export taxes alongside higher income tax and other measures representing 1.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) in revenues. Finance Minister Caputo said the fiscal adjustment would have to be pursued by other means and said the executive government has the tools available to deliver a balanced budget in 2024, which will involve a combination of tax increases and expenditure cuts adding to 5.0% of GDP.

The removal of the tax revenues measures highlights the risks in the reforms process. Unions will fight against the measures that lowers their budget and influence. Liberalising too fast could lead to unintended consequences in the economy and/or lead to an increase in unemployment at the first stage. Against that background, strikes can bring a popular appeal when people are desperate. Milei needs to implement most of the hard reforms while his popularity is elevated and keep the congress coalition by his side. Finally, contingent liabilities need to be monitored. The largest one is the Repsol lawsuit from YPF nationalisation in 2012, which was estimated to be as high as USD 16bn last year.4 Nevertheless, no transformational reforms were ever easy. Milei’s good conciliatory start is encouraging.

Act 1

Chainsaw to Regulations

“Another important conclusion of the Argentine experience is that the fiscal adjustment, understood as a reduction of the government expenditure, as well as the reduction and the elimination of budget deficits are the keys to stabilization after decades of instability, the origins of which are mainly found in the monetary financing of persistent fiscal deficits.” Domingo Cavallo.”5

The first measures taken by Javier Milei government have been described as “shock therapy”. This is perhaps too aggressive of a name, a manifestation the kind of primitive psychiatry that did more harm than good. “Fixing severe economic imbalances”, or perhaps “tough love”, are better terms for the initial policies. The most important adjustments to be made are the foreign exchange rate, removing subsidies, eliminating fiscal deficits, and dealing with short-term debt imbalances. Much of the policy proposed by Milei in his Emergency Decree and Omnibus Bill were built to address these fundamental issues, as well as several imbalances described below:

1. Foreign Exchange

The foreign exchange (FX) market is the bedrock of the global economy. A fully functioning and free FX market permits the private sector to move capital in and out of the country seamlessly, allowing for capital and technology transfers via the capital account. It also allows for the optimal division of labour between countries, as the invisible hand of the private sector takes advantage of relative prices internationally. A countries’ productivity improves when it exports the goods and services where it has a competitive advantage and imports the ones that are cheaper abroad. On the other hand, FX controls create large imbalances in an economy. When these controls are derived by an acute shortage of foreign exchange, they hinder foreign companies from remitting profits made abroad, leading to less investment in the country. It also increases the cost of imports. In the extreme, a shortage of currency for imports means factories cannot get the basic materials, and consumers cannot buy goods that the country does not produce. Poor fiscal discipline, currency shortages and monetary policy expansion are the main ingredients for a hyperinflation recipe.

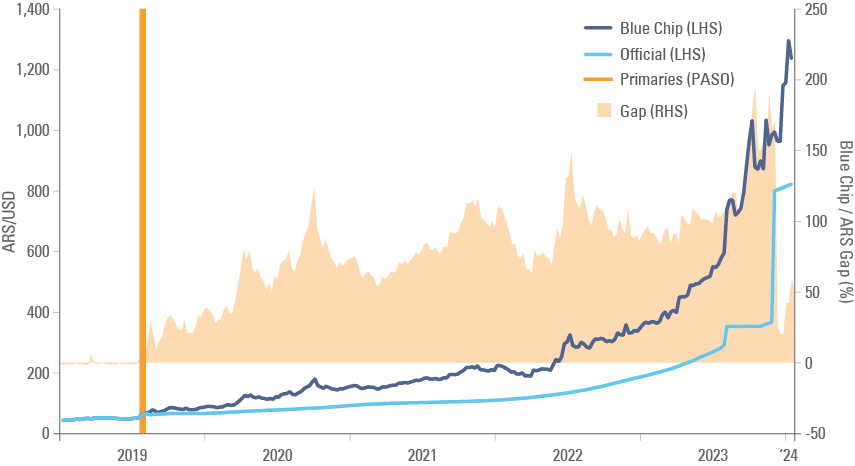

At the same time, shortages of FX always come together with a parallel (often illegal) FX market. The parallel rate for Argentinian Pesos to Dollars can be measured by the difference of the price between Argentinian stocks listed both in the local stock exchange and a foreign one – the so-called ‘Blue-Chip Swap’. Investors with access to both local and international stock markets can buy a stock in the local exchange with ARS and sell it in a foreign exchange (in this case an American Depositary Receipt) receiving Dollars abroad and then cancel the ADR against the local stock.

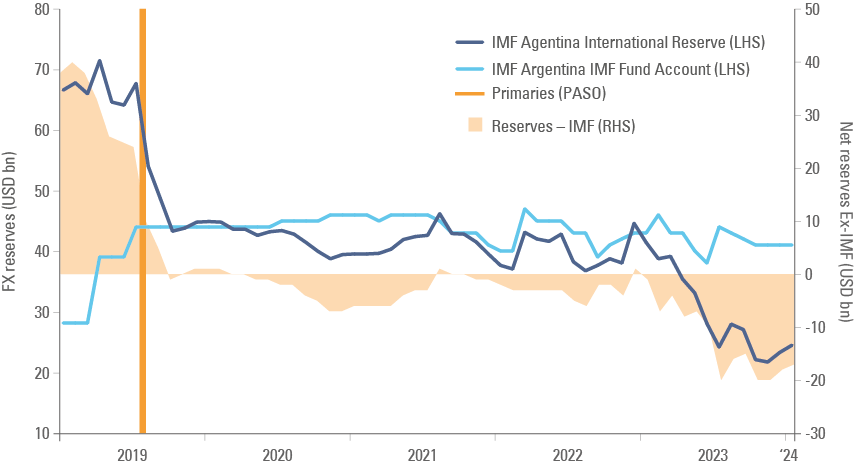

The larger the gap between the official and the parallel rate, the larger the distortion. In the case of Argentina, the distortion started in 2019, when Macri lost the primaries to the Peronist Alberto Fernandes, leading to a massive outflow of foreign exchange reserves as depicted by Figs 1 and 2. The Macri administration had borrowed a significant amount of dollars from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The dollars were quickly sold via the central bank to the private sector, who were fearful of the return of the Peronists to power. The IMF allowing billions of dollars to be sold in the market to defend an indefensible currency peg was one of the most blatant mistakes in the history of the fund, in our view. Defending a fundamentally overvalued ARS ahead of an election was an unwise way of spending borrowed dollars.

Fig 1: ARS/USD and Parallel FX Gap

Fig 2: FX Reserves and IMF Debt

One of Milei’s first acts was to implement a devaluation from ARS 364 to ARS 800 / USD and a “crawling peg”, which allows the official ARS to depreciate by c. 2% per month. The adjustment initially worked. As per Fig 1 the gap between the official and blue-chip swap rate collapsed from 190% on the 24 November to 19% on 29 December and FX reserves increased by USD 3.4bn from its lows on 10 November to 18 January. However, still critically low levels of FX reserves (negative after excluding IMF debt) show that some currency imbalances remain. The central bank cannot remove all foreign exchange restrictions until it accumulates enough FX reserves to render the system stable.

On top of pent-up demand for imports, since 2021 Argentinian corporations have borrowed USD 14bn abroad. They now owe a total of USD 36bn, of which USD 21bn is credit for goods imports. This deep, ongoing shortage of foreign currency explains why the parallel rate has moved from c. 1.0k at the time of the devaluation to c. 1.3k today, representing a 56% gap to the official ARS. This gap will be closed during ‘Act 2’, in our view, by further FX depreciation in the official rate (but probably less than implied in the blue chip rate) and stronger exports from agriculture producers. The 2024 harvest is anticipated to be better, after a disastrous 2023.

2. Fiscal Imbalances

Milei was very clear in his inaugural speech: “No hay plata” (there is no money). Finance Minister Luis ‘Toto’ Caputo has pledged to achieve a 2.0% primary surplus in 2024 (zero nominal deficit), from a 3.0% primary deficit in 2023. While not enough to stabilise debt/GDP in the short-term, it is a monstrous adjustment in the first year, which most people thought impossible until very recently. Argentinian’s will have to undergo a “period of hardship” to balance the fiscal deficit that the country has been running for many years. Caputo will likely achieve these savings mostly on the following areas:

Fuel Prices and Electricity Subsidies

Energy subsidies have hovered around 2.0% of GDP for the last four years, with 70% explained by subsidies to electricity consumers. Over the last decade, these subsidies have accounted for more than 10% of the Argentinian budget. Milei plans to cut all subsidies, which currently keep energy bills at less than 15% of their market value. Hiking energy bills is likely to eliminate waste and inefficiencies which are ironically ultimately paid for by the population. After all, the subsidies are funded by money-printing, which breeds inflation – the most regressive hidden tax of all.

Bloated State

Social expenditure accounts for 55% of government spending. Since 2019, barring the inevitable Covid spike, this spending has remained around 11% of GDP. Milei has famously said he plans to “take a chainsaw” to the state, as eradicating the budget deficit will be a key step to reducing inflation. The success of the strategy will hinge on the government’s ability to cut ineffective social programs such as transport and business subsidies, which primarily benefit the middle class, whilst bolstering schemes which target poverty more directly. For example, the plan will double the universal child allowance, and increase a food card programme by 50%.

Transfers to Provinces

Caputo has affirmed that money available for discretionary transfers to provinces “will be reduced to the minimum”. One of Milei’s main pledges is to halt all new public infrastructure expenditures, affecting all provinces who rely on federal financing to fund projects. From January to October 2023, provinces received around USD 750m in capital transfers, with 23% of those for roadworks and another 10% for public buildings. Moreover, in the recent negotiation in Congress, local governments asked the federal government to reduce the threshold for individual income tax payments (lifted in Q2-2023 in a populist measure by former finance minister and presidential candidate Sergio Massa) and close to 2/3s of the revenues goes to the Provinces. This measure was removed from the omnibus bill alongside higher taxes for exports, but maybe used as quid-pro-quo for future measures with Congress.

Corruption

A larger state begets more corruption. Milei’s libertarian vision revolves around bringing down the centralised controls in Argentina that perpetuate corruption, which is perhaps most evident in the complex import permit system. This operates on access to the official exchange rate, breeding bribery and favouritism while hindering fair trade and competition.

3. Micro Economic Imbalances

In an economy with such large macro imbalances, micro imbalances abound. There is a large amount of de-regulation policies in the emergency plan and omnibus bill proposed by Federico Sturzzenegger that will be crucial to boost private sector investment and productivity.6 The deregulation measures including repealing a law that granted the government power to dictate margins, prices, and volumes, for example. Another measure is to eliminate strict rules for homeowners on rental of properties. The sweeping changes in the labour market proposed by the executive order – such as eliminating automatic deductions on owner’s wages to unions and increasing flexibility – are not yet valid, after one of the Unions successfully challenged the EO in court. But unions are not as strong today as they seem, in our view. Several sees their leaders as corrupt and ineffective at protecting worker’s rights.

4. Debt Profile

- The most pressing problem Milei had to deal with when assuming office was the mountain of short-term debt accumulated both by the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) and the Treasury. Monetisation led to large amounts short-term debt:

- The BCRA had to issue short-term debt (Leliqs and Repos) to absorb the excess liquidity created by their monetisation. Interest rates were kept just above running inflation, so the instruments protected other banks’ cash balances. But with inflation and interest rates running above 100%, the mountain of short-term debt soon increased to around 10% of GDP. Furthermore, Argentinians forced to finance the government’s c. 5% fiscal deficit were asking for protection against FX depreciation. This forced the treasury to sell bills that were linked to the dollar or to inflation, which became cripplingly expensive. Local debt increased from 14% of GDP in 2019 to 30% of GDP in Q3 2023, with 96% of it linked to the consumer price index (CPI) or the dollar.

- The short-term debt problem is the main reason why the Central BCRA Bank is keeping a negative real interest rate policy. Today’s reverse repos (bank deposits at BCRA) pay c. 9% interest per month, against inflation above 25%. This negative real interest rate lowers government indebtedness while forcing banks to accept restructuring at more favourable terms.

At the end of Act I, Caputo will have to negotiate a roll-over of the short-term debt to reduce the uncertainties in Argentina’s financial markets. The government needs first to approve and deliver on their massive fiscal adjustment and explain the incoming monetary stabilisation plan in Act II. Together they will lower inflation significantly, so debt can be rolled at interest rates that are more palatable for the government while also a decent deal for the banks.

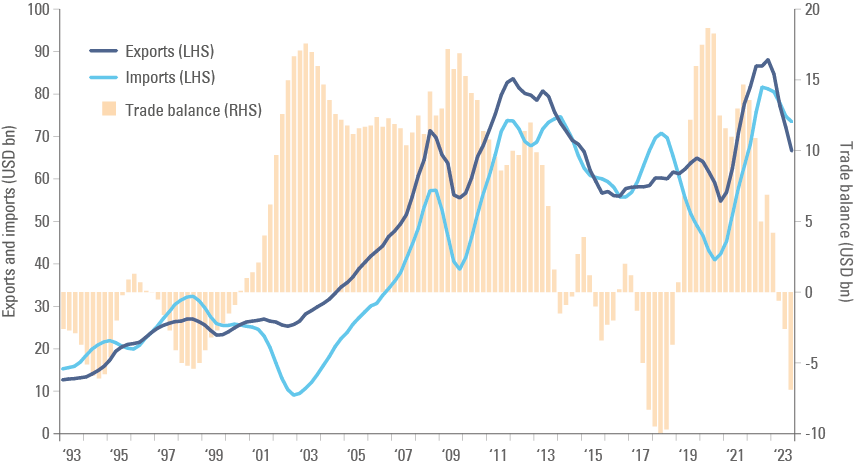

- Dollar Debt vs Exports: Several analysts believe Argentina can’t generate dollars to repay its external debt. The reality is that Argentinian debt is not massive for its external sector. Since 1993, the economy generated a trade surplus in 21 years. The average surplus was USD 5.3bn, and the economy generated a surplus north of USD 10bn for 13 out of the last 30-years, as per Fig 3.

Fig 3: Annual Rate of Trade (Not Seasonally Adjusted)

This robust external sector contrasts with private sector debt repayments of USD 4.4bn in 2024 and USD 9.5bn in 2025 and 2026. The IMF and other multilateral debt bring the total repayments to USD 16.0bn in 2024, USD 16.4bn in 2025 and USD 17.1bn in 2026. No country in the world repays its debt when it comes due. What is needed is the credibility to roll it over. In our view, official creditors will be very willing to roll the debt (and perhaps lend new money) if macroeconomic policies are moving towards stabilisation.

In summary, to successfully achieve the Act I objectives, removing economic inefficiencies, implementing fiscal reforms and local debt reprofiling are the key measures. These is likely to allow the government to end debt monetisation and improve private sector confidence in Argentina. The reforms adjusting the micro imbalances are also extremely important, but their benefits would be felt, in the short term, via investments inflows from the private sector in the expectation of a better business environment to come. Thus, Milei can take his time in implementing micro reforms by building a broad consensus across parliament and society to avoid future challenges.

Act 2

Monetary Stabilisation Plan

After implementing reforms that bring the fiscal accounts to a surplus and rolling over the local currency and official foreign currency short term debt, Argentina should be able to commence a monetary stabilisation plan.

When?

The earlier the better. If Milei can set the ball rolling in Q2 2024, it is likely to allow for a fast decline in inflation and for foreign investments to hit Argentinian shores, ahead of mid-term elections in October 2025.

How?

Argentina can find inspiration in Brazil. From the mid-1980s to the early 1990’s, the Brazilian economy was struck by hyperinflation and indexation. The initial trigger was the balance of payment crisis following the oil shock and the external debt default that followed in the early 1980s. But the root of the inflation problem was monetary. Notably, sub-national states had poor fiscal discipline and relied on the banks that they owned to finance their profligacy. The consequence was an inability to control the general government debt or monetary policy. In 1993, Persio Arida, Andre Lara Rezende, Edmar Bacha and other economists devised a monetary stabilisation plan with three phases. A fiscal consolidation, renegotiation of sub-national states’ debt and a bank recapitalisation plan were the first necessary steps. These were followed by the introduction of a monetary unit (‘Unidade Real de Valor’ or ‘URV’), that would exist in parallel with the existing currency. The plan was to give credibility to the new currency before it was created, by indexing the URV to the Dollar. Consumers thus saw prices of goods increasing (inflation was close to 50% per month) in the old currency terms but remaining stable or sometimes even declining in this new unit of account.

When the new Brazilian Real was introduced at 1:1 with the URV, its value remained pegged to the US dollar. This was important, leading to a large increase in the purchasing power of the population in the following months. Over time, inflows from foreign investors to Brazil allowed the new currency to appreciate against the dollar. The inability of sub-national governments to overspend and better control of state-owned banks allowed for better fiscal discipline and the increase control over tax revenues allowed federal government revenues to increase.

An easier path

The case of Argentina may be less complicated than in Brazil. After all, Argentina is not experiencing hyperinflation of as much as 5,000% inflation per year (yes, five thousand percent), as Brazil did in the late 1980s to early 90s. Inflation reached 25% month-on-month in January in Argentina, but mostly because of the increase in previously over-subsidised energy prices. Today, the BCRA is no longer monetising the government’s debt. Meanwhile, fiscal austerity measures have started to kick in, meaning that most economic actors will be unable to repass higher prices into their goods, given the weaker demand environment. Consequently, the secondary effects of inflation will be smaller. Prices are likely to begin declining as soon as the adjustment resulting from cutting subsidies is over. While fiscal austerity will be a key tool in reducing inflation, importantly, Milei has maintained transfers to the poorest of the population to avoid a social disaster.

Therefore, all the BCRA will have to do in the second phase of the plan is to increase interest rates to very positive levels in ex-ante real terms (i.e. one-year rates moving above next 12-months inflation expectations). In our view, initially Argentina should offer 10-20% real ex-ante rates. These may decline towards 5 -10% as inflation fell below to c. 2% per month and 0-5% as annual inflation normalises to single-digit levels.

Real interest rates and the absence of debt monetisation will likely provide a monetary anchor, with a budget surplus as the fiscal anchor. Importantly, the BCRA will want to depreciate the ARS to a level where the gap with the parallel rate fully closes, before tightening monetary policy. This could maximise the inflows from exporters while investors would be willing to convert dollars to buy cheap assets, encouraging repatriation of money held in foreign accounts as well as foreign investment. In this backdrop, local currency bonds could be a sound and lucrative investment, as could stocks trading on the Buenos Aires Stock Exchange, and real estate in Buenos Aires.

This inflow of dollars would be crucial in allowing the BCRA to accumulate FX reserves and lower the country’s risk premium, bringing further confidence that the value of the currency can be maintained and further momentum to capital inflows. For both the currency and the budget surplus, it will be very helpful if the 2024 harvest is as strong as many expect (the weather has been very good) and oil and gas production does indeed ramp up.

Act 3

Consolidating its New Fiscal/Monetary Stability: Dollarisation?

Simply speaking, an economy is dollarised when it opts to use the US dollar for all economic transactions within its borders. Giving up the national currency may have positive psychological effects if trust in the national currency is broken. Equally, perception can be negative due to patriotism, or distrust around the US and its institutions.

In strict monetary terms, giving up the currency means giving up autonomy over monetary policy. Dollarisation means that the country in question absorbs the monetary stance adopted by the US Federal Reserve (Fed). A country may also replicate the Fed’s monetary design by simply pegging its own currency to the greenback. Hong Kong and the Gulf Countries have held successful currency peg regimes for decades. However, aside from some practicalities, the difference between full dollarisation and the hard peg is largely psychological. What determines a successful dollarised regime is not its full adoption (Panama) or a hard peg (Hong Kong, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates), but whether the country’s fiscal accounts, banking system and economy are working towards keeping a stable system.

Building a Stable System

There are four key elements for a stable pegged/dollarised economy:

- Fiscal accounts

- FX reserves

- Economy openness and competitiveness

- Banking system

1. Fiscal Accounts

Milton Friedman’s principal insight is that there is no monetary stability without long term fiscal stability. Loose monetary policy is not inflationary, per-se. But keeping monetary policy loose to finance large fiscal deficits most likely will be. Poorly devised and unsustainable fiscal policies are one of the main sources of uncertainty for Emerging Market countries. For the financially savvy population of any country, fiscal profligacy raises alarm bells as runaway debt has led to many examples of sovereign default and subsequent impoverishment.

In the past, several economists have advocated for dollarisation as a means of ensuring a level of fiscal austerity. However, a paper by former Central Bank Governor and IMF Latin America Chief Ilan Goldjfain studying different dollarisation experiences in Latin America (Ecuador, Costa Rica, Argentina, and Panama) finds no empirical evidence that dollarisation (USD adoption or hard peg) did so.7 Therefore, fiscal discipline is a necessary but insufficient condition for dollarisation. The other conditions needed for dollarisation’s success are related to the structure of the economy and its banking system.

2. Foreign Exchange Reserves

The most obvious condition for dollarisation, is... well... to have dollars. Without dollars it is impossible to peg your currency credibly and sustainably to the Greenback. After all, the central bank must guarantee the currency’s convertibility, implying a promise to sell (and buy) unlimited amounts of dollars to satisfy private sector transactions.

There are no fixed rules for minimum reserves; it depends on the monetary system adopted by the country. The less flexible the currency, the more liquidity (including FX reserves) is needed to guarantee the peg.

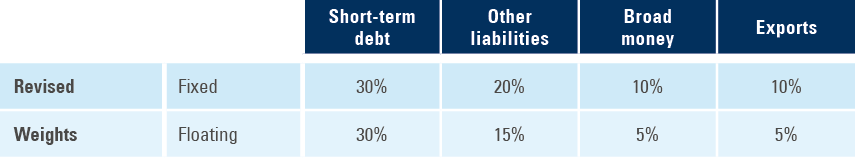

The IMF does not believe countries need to hold a minimum amount of FX reserves. However, they emphasise the importance of FX reserves for EM economies, especially after observing the stabilising effect of a focused FX reserve accumulation by many EM countries in the 2000s. The organisation has published a series of papers to measure the Analysis of Reserve Adequacy (ARA), with the

main table is depicted on Fig. 4.8

Fig 4: IMF Analysis of Reserve Adequacy

3. Economic openness and Competitiveness

The main disadvantage of a currency peg is its deprival of a simple mechanism (flexible foreign exchange) that allows the economy to adjust to shocks. An economy that becomes less competitive in relative terms with its main trading partners will tend to see a weaker currency over time. But if the currency is pegged, the adjustment will take place via less activity – an economic recession – to force relative prices to adjust and compensate for the lower competitiveness. Successful dollarisation typically involves small, open economies (i.e. Hong Kong) or economies with structural dollar surplus (via exports) which typically have accumulated a lot of reserves (Saudi Arabia, UAE). Hong Kong is a very open economy, while Saudi Arabia and the UAE have an advantage in a strategic sector (oil), leading to large savings. Argentina shares neither of these attributes. But Milei’s ambition is to create these conditions by radically opening the Argentinian economy to the international private sector. If that condition is not satisfied, dollarisation will hold credibility only if Argentina keeps a very elevated amount of FX reserves.

4. Banking system

Another key element in a dollarised economy is its banking system. In fact, the IMF doesn’t prescribe a large amount of FX reserves to a dollarised economy. As long as there is enough liquidity in the economy via its banking system, the country’s dollarisation would remain viable. This is the case of Panama, which holds very low FX reserves (its ARA score in 2023 is 0.2 – even lower than Argentina’s at 0.72). It is the ample liquidity, openness and strength of Panamanian banking system that guarantee the peg to the Dollar is unchallenged.9 This institutional quality, along with the strategic importance of the Canal allows Panama to be irresponsible, in terms of fiscal and economic policies, for longer periods than its EM peers.

5. Will Argentina Dollarise?

Today, Argentina has neither dollars in its central bank nor the economic openness and institutions in the private sector required for a dollarisation. But the path of reforms laid out by Argentina (Act I) and considered by this paper (Act II) would allow the country to pursue dollarisation on its final economic reform act (Act III).

In our own view, Milei will try to pursue a hard dollarisation of the economy as he probably believes that this would be the best way of safeguarding his liberal reforms. Will the Argentinian society be willing to do it? Well, if Milei accomplishes half of what he is planning to and foreign investment returns, he maybe be so popular that he will be able to convince the population on the best path forward.

It is important to keep in mind too that, in a way, economically-savvy Argentinians have already adopted the dollar to accumulate savings. Today these dollars are under the mattress in Argentina or in bank accounts in Montevideo, Panama, the US, or even in the United Kingdom. Emilio Ocampo, one of the most prolific economists defending dollarisation, estimated in a blog post that there are USD 200bn held by Argentinians. All that is necessary for dollarisation is for c. 20% of these dollars to return to Argentina alongside foreign investments.

Summary and Conclusion

The most interesting investment opportunity in 2024 is also the most controversial. Investing in Argentinian assets could deliver extraordinary returns, if Milei manages to implement his most essential economic reforms. However, even optimistic economists and analysts struggle to see an open path for these economic reforms to work. This paper does so, proposing the ideal reform sequence, by which Argentina can regain the economic dynamism it displayed in the late 19th Century.

Milei, with the support of Sturzenegger and Caputo is now engaging on Act I, restoring economic competitiveness, balancing fiscal accounts and re-profiling a mountain of short-term debt. This act will be the most difficult to pull off, as it directly challenges the establishment – the Unions and Peronists who have held power for nearly 75 years.

Act II will be simpler, involving a monetary stabilization plan, through which Argentina should benefit from a triple inflow of Dollars from exporters, foreign and local investors.

The third act will be the notorious dollarisation. This will be the least crucial but most controversial of the reforms, in our view, and may become the theme of many Tangos in the future.

1. See - Pacino dances Por Una Cabeza in Scent of a Woman https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F2zTd_YwTvo

2. See - https://books.google.com/books?id=8uv7WrI4cE4C&pg=PA12

3. See - https://www.euronews.com/2023/12/23/what-might-happen-to-argentina-after-mileis-mega-decree

4. See - https://www.reuters.com/legal/us-judge-rules-against-argentina-following-ypf-payout-trial-2023-09-08/

5. See - https://www.kansascityfed.org/Research/documents/6775/Cavallo_Jh96.PDF

6. See - https://batimes.com.ar/news/economy/federico-sturzenegger-architect-of-argentinas-reforms-says-he-isnt-even-halfway-done.phtml

7. See - https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=228898

8. See - https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/datasets/ARA and http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2016/060316.pdf

9. See - https://www.elibrary.imf.org/configurable/content/journals$002f002$002f2023$002f129$002farticle-A003-en.xml?t:ac=journals%24002f002%24002f2023%24002f129%24002farticle-A003-en.xml