Egypt’s currency macro rebalancing was the main Frontier Markets event of the month. The plan involved several bilateral and multilateral deals, and policy announcements that seemed disconnected at first but suggest a deeper strategic move with big implications for the region.

Monetary policy reforms

Last week, Egypt announced that the Egyptian Pound (EGP) would float, with the non-deliverable forward fixing rising to 49.64 from 30.90 on the prior day. A few hours before the devaluation, the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) announced a 600 basis points (bps) hike on its deposit, discount, and lending policy rates to 27.25%, 27.75%, and 28.25%, respectively. The CBE statement unpacked an orthodox stance to its foreign exchange (FX) policy, calling for a unification of the various exchange rates and a free-floating FX regime anchored by a nominal inflation target.1

An oasis of liquidity

Authorities should not be attracted by currency peg ‘mirages’ of false stability. Healthy intraday volatility, in accordance with capital flows, would discourage ‘flighty’ short-term inflows seeking a quick buck. Long-term investors that understand the fundamentals of the Egyptian economy will be tempted to take the long trip in the Sahara if the EGP market is healthy, functioning, and transparent. After all, a fully free-floating EGP may be inconvenient, but it should also mean the so-called ‘queue’ of foreign investors and importers will dissipate.

A huge deal

The most interesting element of this Egyptian saga was announced in the previous week. Only two years after establishing an office in Cairo, ADQ, one of Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth funds, announced a USD 35bn investment in a tourism project in Egypt in Ras El-Hekma, located 350km from Cairo or a two-hour drive from Alexandria. The project is an ambitious 170 million square metres city comprising mostly tourist amenities, but also a free trade and investment zone including residential and commercial real estate. Essentially another Dubai, in North Africa.

ADQ paid USD 24bn to acquire 65% of the Ras El-Hekma development, with an additional USD 11bn to be invested in real estate and other prime projects. As part of the deal, ADQ will convert USD 11bn of deposits that are already in the CBE to invest in “prime projects across Egypt to support its economic growth and development.” The overall project is likely to be much larger than the USD 35bn commitment.

“ADQ’s experience in providing fully integrated infrastructure solutions across a broad range of services, including energy, water, transportation, and real estate, promises to bring significant benefits to the new development and Egypt’s economy, and is expected to attract over USD 150 billion in investment.”2

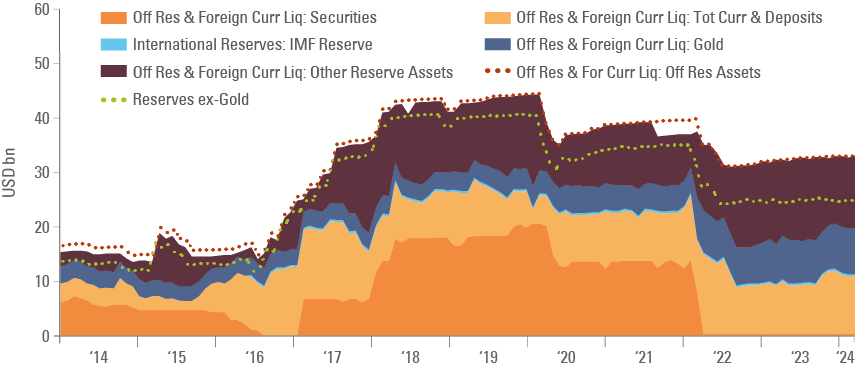

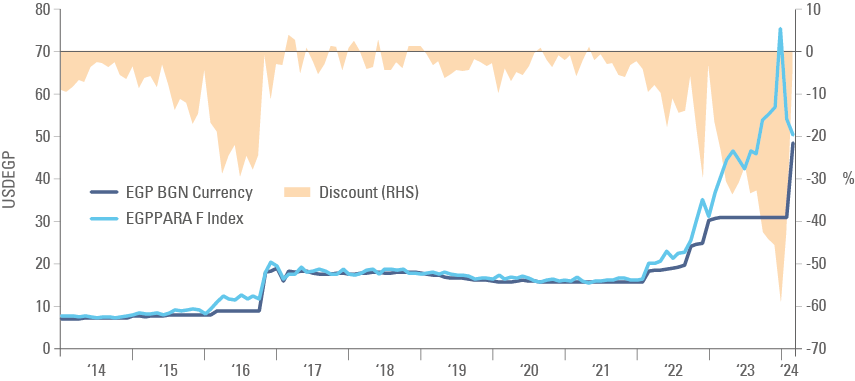

To put things in perspective, in February, Egypt had USD 25bn of FX reserves, excluding gold, of which USD 11bn were deposits from Abu Dhabi, as per Fig. 1. The USD 24bn payment for the right to acquire Ras El-Hekma can potentially double the country’s current levels of reserves ex-gold. Since March 2022, the liquid component of the FX reserves has been virtually depleted due to large outflows from foreign investors holding government bonds. Egypt was faced with USD 21bn outflows in 2022 and USD 4bn in 2023. This is also the same period in which de-facto capital controls were imposed, leading to a widening of the parallel FX rate illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig 1: CBE international reserves

Fig 2: EGP official and parallel rate

The increase in FX reserves will make the country’s external and overall debt more sustainable. At the time the deal was announced, Egypt had USD 37.4bn of Eurobonds outstanding. On the day before the FX devaluation, Egypt had EGP 2.5trn of outstanding short-term bonds (T-bills). This was equivalent to USD 81.4bn prior to the devaluation but shrank to USD 50.7bn post-devaluation. Against that, Egypt’s main sources of dollar revenues are its transportation (mostly Suez Canal), tourism, and remittances, which in 2023 amounted to USD 14bn, USD 13.6bn and USD 22.1bn, respectively.

More importantly, the parallel and official exchange rates converged at a level that renders Egypt very competitive. At EGP 50 per Dollar, the currency is marginally cheaper, in real effective exchange rate terms, than it was after the 2016 devaluation – the lowest level since 1993. Of course, the FX devaluation will also lead to a sharp decline in the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), in Dollar terms, in the short term, so the stock of debt to GDP will temporarily increase. Nevertheless, the deals massively increased Egypt’s ability to service its debt.

Here comes the cavalry!

The IMF seems to have coordinated the timing of the deal announcement with the ADQ investment. The fund has an important role to play, particularly in the coordination and monitoring of economic and monetary reforms.

The size of the IMF programme is also relevant. The Extended Fund Facility (EFF) programme increased to USD 8bn, from USD 3bn. The main conditionalities are floating FX and inflation target regimes and further fiscal consolidation, including lower public sector investments. Crucially, the ADQ deal allows Egypt to slow investment in infrastructure without sacrificing growth. Furthermore, the IMF agreed on the need to increase social spending to protect vulnerable groups, expanding the cash transfer programmes along with an additional EGP 180bn (USD 3.6bn) of social spending in the July 2024 to June 2025 fiscal year.

Alongside the IMF comes a cavalry of multilateral banks and the European Union (EU). This week, Finance Minister Mohamed Maait said the total package agreed with multilateral banks and the EU could exceed USD 20bn. This includes USD 3bn from the World Bank, USD 1.2bn from the Green Climate Fund, assistance from the African Development Bank, and EUR 7.4bn (USD 8bn) from the EU.

The EU amount comprises both aid and loans to shore up Egypt’s economy. The funding would be disbursed until the end of 2027, contingent on meeting targets within the IMF programme. European countries are naturally concerned that the conflicts in Gaza and Sudan may lead to social instability in Egypt, which could potentially increase immigration pressure on Europe. The agreement includes support for the energy sector and assistance to deal with Sudanese refugees.

Play it again, Sam

This one-two punch of monetary reforms followed by ‘white knight’ foreign capital and the IMF is not new. Egypt did that in 2016 when the CBE announced a devaluation and rates increased after securing a currency swap agreement of RMB 18bn (c. 2.6bn) with the People’s Bank of China and an IMF deal.

The playbook was tested before and counted on significant structural reforms. In fact, the results of several of these reforms were laudable. Egypt’s fiscal accounts moved to a primary surplus as revenues became more predictable – the gap between estimated and actual revenues declined.

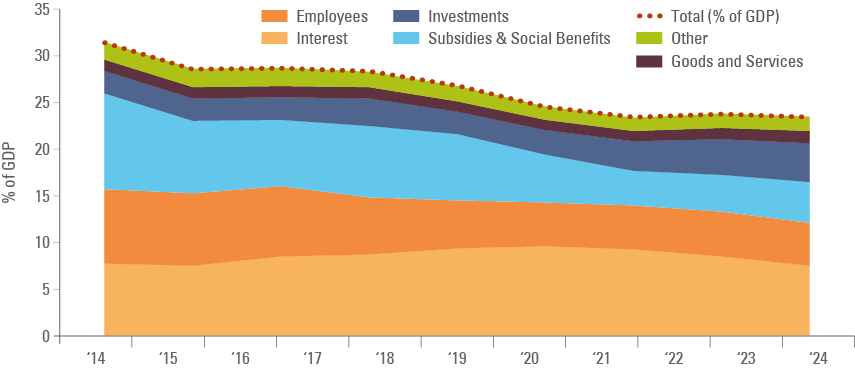

Even more impressive, Egypt achieved the primary surplus by aggressively cutting expenditures, which declined from 31.3% of GDP in 2014 to 20.3% in 2023. Employees expenditures halved from 8% of GDP to 3.9% over the period, as subsidies declined from 10.2% to 3.8%, as per Fig. 3:

Fig 3: Egypt’s expenditures

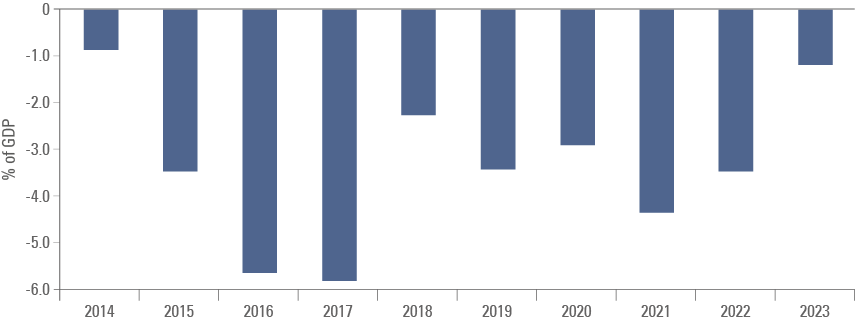

The external accounts also improved significantly, not only due to the initial impact on the reforms in the trade deficit, but also the ramp-up of gas production thanks to the Zohr Gas field, which allowed Egypt to become virtually self-sufficient in energy. The expansion of the Suez Canal and tourism revenues were also increasing. The latest devaluation, alongside a massive increase in Dollar flows, will bring stability, at least in the short term, to the external accounts. The current account was already in a much better position, as per Fig. 4:

Fig 4: Current account balance

A new balance of power

The Egyptian rebalance also illustrates the fast-shifting balance of power. The big regional players are setting up a new structure for a world where the United States (US) is no longer a bastion of security for the Middle East, in our view. Egypt is the MENA country with the largest Arab population, which brings tremendous potential, but also risks. The war in Gaza and the Civil war in Sudan made Egypt an even more important geopolitical concern. That’s why the UAE’s support is likely, in our view, to come with strings attached in the format of structural reform to support social stability.3

The fact that Egypt is being basically bailed out by the UAE is relevant. The strength of the Abraham Accords and the fact that UAE and Saudi Arabia did not severe ties with Israel, in the face of the ongoing war in Gaza is relevant. The fact that Saudi Arabia has re-established diplomatic relations with Iran is relevant. On top of it, China trading commodities in RMB and the partnership of Russia with OPEC set up a much more complex balance of power. The large regional players are proving their independence to pursue their own strategic interests.4

Tackling the challenges

There were three main problems which did not allow Egypt to find macroeconomic stability, despite its impressive progress in implementing the IMF reforms:

1) Interest Payment in Local Debt

Egypt has a large stock of local debt with a very elevated yield, which kept interest expenditures on average at 8.3% of GDP over the last decade. It had recently declined to 6.9% in 2023, but it is likely to increase again because of the post-reform monetary tightening, as per Fig. 5.

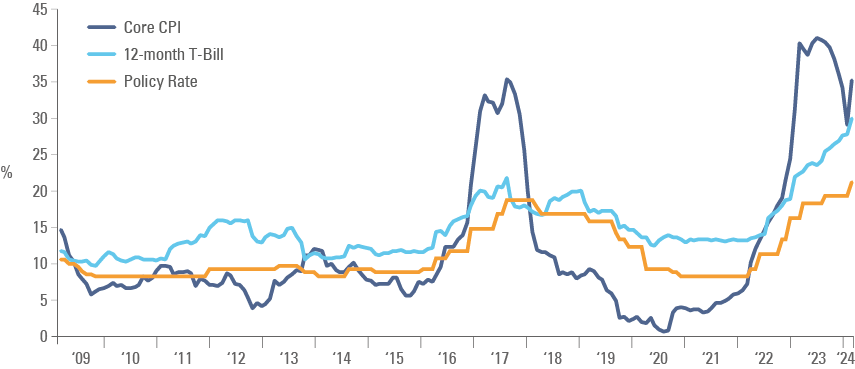

Fig 5: Egypt’s policy rate, 1yr Bill and Core CPI

Egypt needs structural reforms that will allow for more competition across industries, a crucial factor to bring inflation lower. A fully floating currency would also allow for a smoother adjustment of its external accounts during crisis, which should lower the magnitude of the inflationary spikes.

2) Government control of the economy

A well-known problem any Egyptian businessperson must deal with, is the heavy presence of the government and the military across sectors. Successful private sector companies often must deal with a competitor with closer relationships to the government – an unfair playing field. Monopolistic behaviour and corruption practices across the economy are key factors keeping inflation elevated.

The recent commitment to privatisation is encouraging. Egypt has announced a few regulatory reforms guaranteeing private sector companies an arms-length competing position across sectors. Egypt’s sovereign wealth fund was tasked with finding state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that could be sold.5

Progress has been slow, in part due to the FX uncertainty. The petrochemical sector offered foreign investors the opportunity to invest in Egyptian assets that earn foreign currency, which provides some protection. There are several other sectors, including consumer, which the government wants to privatise. This process is likely to accelerate with the measures taken to stabilise macro conditions.

The UAE investment also signals serious changes on that front. It is hard to believe that ADQ would commit close to 15% of its current capital to a large high-profile project in Egypt unless it believes in structural reforms that would lower inflation and bring a more stable operating environment.

3) External vulnerabilities

Egypt enjoyed a large improvement in the current account deficit post the 2016 devaluation, with the current account deficit improving from 5.7% of GDP in 2016 to only 2.3% in 2018. The fact that the currency was pegged after 2016 and that inflation remained relatively elevated against its trading partners meant that the currency became ‘expensive’ again by Q4 2019, just before the twin shocks of Covid-19 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The first shock lowered revenues from both the Suez Canal and tourism. The second shock led to a sharp increase in food prices – particularly on imported wheat from Ukraine, which Egyptians depend on. The authorities’ reluctance to timely devalue the EGP led to the depletion of reserves and the large gap between the official and parallel exchange rates.

Macro stability and competitive advantages

The UAE deal is really a multi-decade deal with three phases. Initially, it is a carry trade position where the UAE will get paid EGP interest on its deposit until cash is deployed in the project. The second phase is the development of the area, with opportunities for UAE and Egyptian contractors and individuals. The third phase is running the hotels and offices and selling residential units. The project is likely to only be successful if anchored in macroeconomic stability.

Diversifying the sources of external currency revenues is very important, but often much harder than deepening the revenues from a sector where the country has a competitive advantage. Building a tax-free tourist zone in the north of Egypt has the potential to multiply its foreign revenues. Moreover, if well implemented, the new infrastructure may also lead to the development of other industries like financial services, renewable energy, and eventually even manufacturing.

Tourism is an area where Egypt has a lot more potential. On the heels of the ADQ deal, several media outlets have reported Saudi Arabia is interested in investing in tourism projects in the Red Sea. The articles mentioned Ras Gamila, at the tip of the Sinai Peninsula, 4km away from Sharm El-Sheikh airport, and the 280km stretch from Hurghada to Marsa Alam. Coincidently, both areas are opposite to the mega Neom development in Saudi Arabia.

These investments are crucial not only for the external accounts, but also to keep GDP growth elevated and bring more employment opportunities to locals, lowering the risk of social unrest.

Summary and Conclusion

The UAE, IMF and EU deals and the monetary and fiscal reforms implemented, are connected and have the potential to transform Egypt’s economy. Some investors are sceptical that the announcements will differ from the 2016 reforms. This piece illustrates the massive progress made by Egypt on its fiscal and external accounts.

More importantly, it illustrates how the large investment from the UAE has the potential to transform the Egyptian economy, not only due to the direct impact on the economy via the construction and development of the new tourism hub: After all, the investment will only be successful if Egypt achieves macroeconomic stability. The deal is also another element of the shifting balance of power in the region, rendering the Middle East a potentially more stable region, in our view. Investors mistaking this strategic investment for just another ‘blip’ may risk missing a big opportunity.

1. See – CBE Statement

2. See – https://www.adq.ae/newsroom/adq-led-consortium-to-invest-usd-35-billion-in-egypt/#:~:text=ADQ%2C%20an%20Abu%20Dhabi%2Dbased,developments%20by%20a%20private%20consortium

3. See – MENA = Middle East and North Africa

4. See – OPEC = Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries

5. See – https://tsfe.com/pre-ipo.html