Inflation is likely to remain high in 2021. The primary source of price pressures is the rebound in commodity prices after their sharp collapse last year.

The risk that US inflation spirals out of control cannot be dismissed. Both US fiscal and monetary policy spigots are running fully open, supporting aggregate demand while supply disruptions abound. A prudent Fed would follow the example of many Emerging Markets (EM) central banks and adjust its policy stance. If the Fed opts instead to continue to downplay inflationary risks then the US dollar (USD) is likely to suffer significantly, in our view.

EM countries are in a much more resilient position than in the so-called 2013 ‘Taper Tantrum’ and should not be significantly impacted if the Fed decides to reduce asset purchases and/or signal interest rate increases.

US inflation: still not out of the woods

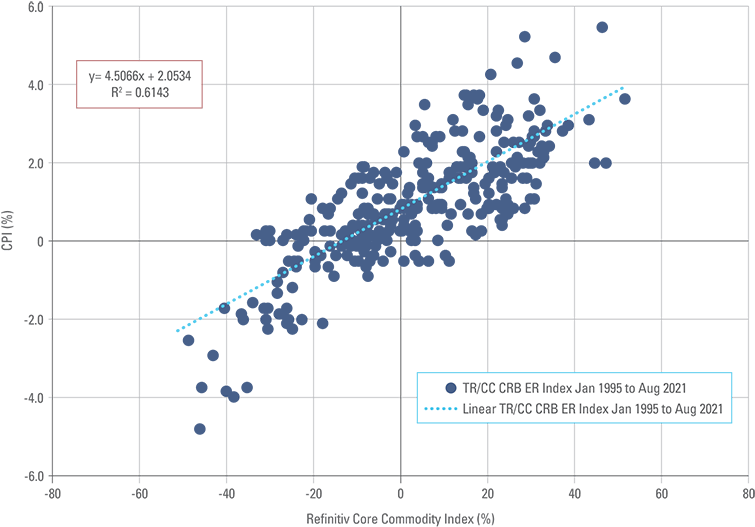

US consumer price index (CPI) inflation rose to the highest levels since 2008 at a yoy rate of 4.2% in April. The number exceeded consensus expectations and was higher than the most pessimistic analysts' estimate as surveyed by Bloomberg. However, the increase in commodity prices over the last 12 months already hinted strongly at high inflation. A simple regression of the Refinitiv Core Commodity Index (CRY) on the 3-months lagged US CPI inflation shows that inflation above 4% was extremely likely (Figure 1).

Fig 1: CRY Index vs. 3-months lagged US CPI monthly data regression from Jan-1995

The likely evolution of US CPI inflation for the rest of 2021

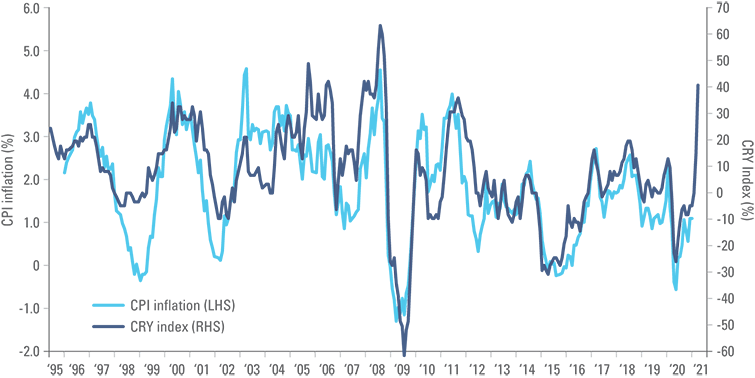

Figure 2 suggests that US consumer prices inflation will remain high through the rest of 2021. Commodity prices are likely to be most elevated in yoy terms in May 2021, which means that the CPI inflation print to be published on 10 June is likely to be even higher than in April.

Fig 2: CRY Index (yoy change) vs. 3-months lagged US CPI (yoy)

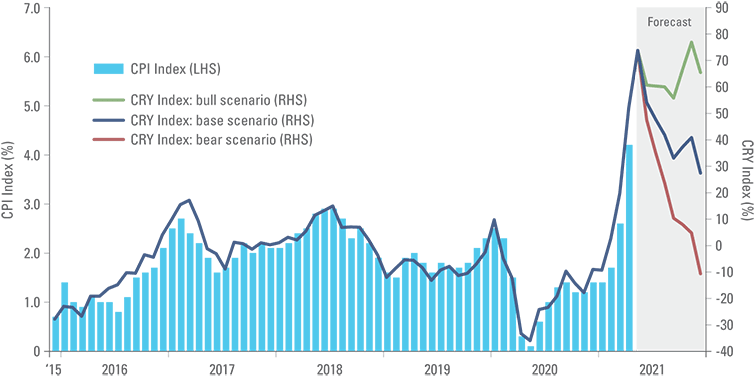

Figure 3 presents a scenario analysis with three possible outcomes. In the base case, commodity prices remain stable until the end of the year. The two other scenarios comprise bull and bear cases for commodity prices, where they rise and fall 30% over this period, respectively. The base case scenario is consistent with US CPI inflation remaining above 3% for the rest of the year. In the bull case for commodity prices, US CPI inflation may stay above 5% until the end of 2021, while in the bear case scenario inflation declines to around 2% by the end of 2021. Currently, the median forecast for US CPI inflation by economists as surveyed by Bloomberg is at 3.0% by the end of 2021 (compared to 2.0% at the beginning of the year).

Fig 3: Scenario analysis: CPI (yoy) vs CRY Index (yoy)

Core inflation

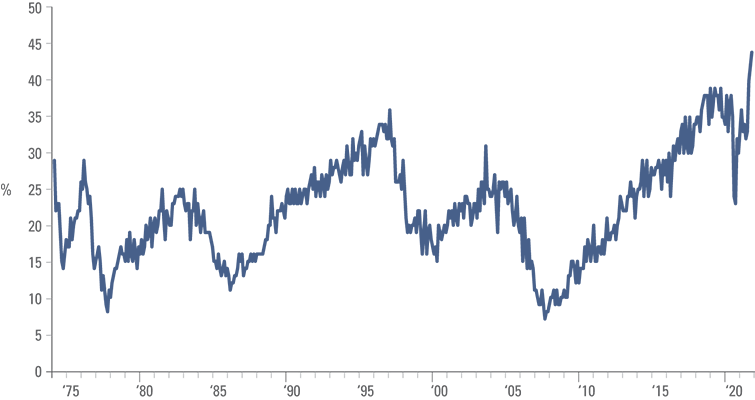

The Fed's preferred measure of inflation, core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) inflation, has a much weaker relationship with commodity prices, since core inflation indices exclude food and energy prices. However, there is also significant evidence of rising inflationary pressures due to shortages of non-commodity goods and services. In addition, the labour market is not rebalancing as expected. The National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) reported that 44% of small companies could not hire employees. This is the highest level in 50 years as per Figure 4, and it is highly unusual that companies struggle to hire workers less than a year following a recession.

Fig 4: NFIB small business job openings hard to fill (% of companies not filling their vacancies)

The broad-based supply chain and labour market disruptions sit uncomfortably alongside the buoyant outlook for aggregate demand over the coming quarters due to generous paychecks granted by the US government. It is not inconceivable that the combination of constrained supply and over-stimulated demand generates significant price pressures across the American economy.

Indeed, Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida acknowledged that inflation is likely to remain elevated in a recent speech1: "The way in which we bring supply and demand into balance in the labour market, especially in the service sector may take some time and may produce some upward pressure on prices as workers return to employment."

In other words, the core PCE inflation may well overshoot the 2% centre of the Fed's average inflation target. Core PCE inflation has not been above 2.5% since 2006 and above 3.0% since 1992.

The latest on EM inflation

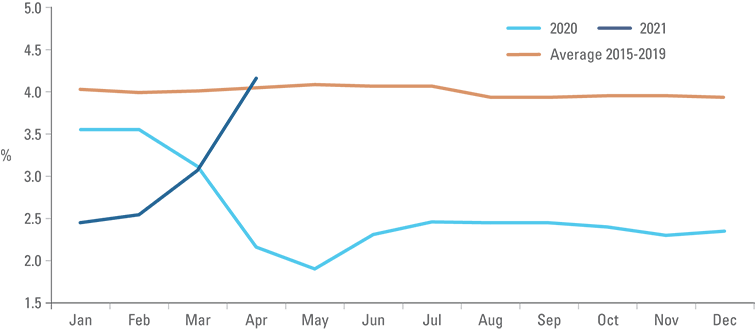

Inflation has been rising in EM countries as well. However, most of the rise is due to base effects rather than extraordinary stimulus measures. The rate of EM CPI inflation declined to exceptionally low levels in 2020 due to the Covid-19 shock (Figure 5).

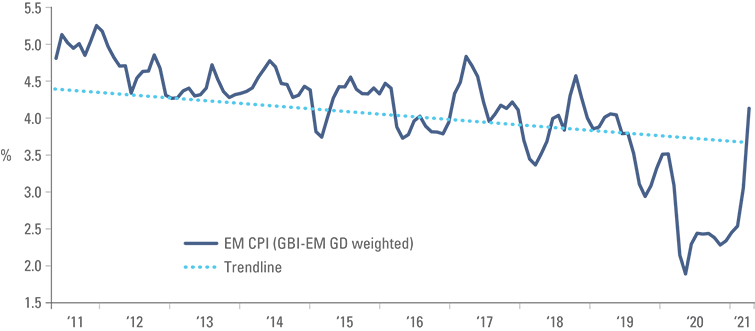

So far, EM inflation has merely returned to the average of the five years prior to 2020 and is likely to rise modestly above the declining trend line for inflation of the last ten years as shown in Figure 6.

In level terms, EM index weighted yoy inflation happened to be at the same level as US CPI inflation in April. This is the first time that EM inflation has equalled US inflation in at least 20 years.

Fig 5: GBI EM GD weighted inflation: selected dates

Fig 6: GBI EM GD weighted inflation: 10 years

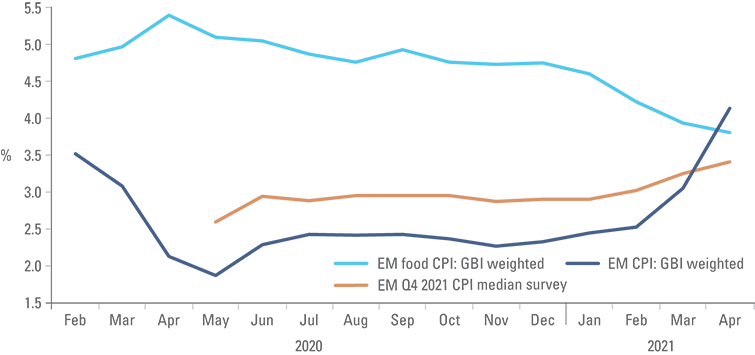

Encouragingly, stronger EM currencies over the last 12 months are already supporting food price declines in most EM countries represented by the JP Morgan GBI-EM GD, including Russia, Chile, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Philippines and China. The only country where food inflation is still increasing is South Africa. Lower food inflation and EM central banks credibility is helping to keep expectations anchored well below the level of actual CPI inflation as illustrated by Figure 7. Furthermore, there are signs that soft commodity prices are peaking as speculative long positions are at the highest levels since 2013 and prices have stabilised somewhat in May. This is important because food is a much larger share of the consumer basket in EM countries than in developed markets (DM). Food prices are also an important source of political pressure, so the decline in prices is good news both from a financial and social stability perspective.

Fig 7: GBI-EM GD weighted food inflation in EM

The Fed's predicament

Most EM countries decisively addressed their inflationary problems in the 1990s. DM inflation has not been a problem since the late 1970s and early 1980s. Ironically, the absence of price pressures for many decades may have obviated inflationary risks, which have been rising since last year(see Ashmore's 2021 Outlook publication2). The overriding determinant of how inflation evolves from here – particularly whether inflation turns out to be transitory or not – will boil down to how central banks react in the current environment of elevated inflation risks.

The US Federal Reserve has so far maintained a well-defined stance. In the Fed's view, inflation is transitory and the Fed should only react if inflationary pressures turn out to be present for an extended time period. This rear-view perspective is dangerous, however. Anchoring inflation expectations and preserving currency stability are the two key primary objectives of central banks.

By opting to be 'actively' dovish the Fed risks de-anchoring inflation expectations, which would result in companies passing higher input prices to their goods and services. If price increases are met with consumers that are less sensitive to prices than before (due to pent-up demand for services or specific goods), this inflationary impulse could become 'sticky'.

This price dynamic would lead investors to sell Treasuries which are likely to deliver negative inflation-adjusted returns due to current low levels of yield. The long end of the US treasury curve would be particularly exposed as it is less controlled by the Fed than the short end of the curve, thus making yields more susceptible to oscillation with changes in expectations for future inflation.

In the current context of US equities trading close to their all-time highs, inflation at the highest level since 2008, and the economy accelerating due to the end of lockdowns and significant fiscal stimulus, the Fed has few excuses for not changing their policy stance by signalling a reduction in asset purchases, in our view.

Fed members Richard Clarida, Robert Kaplan, and Charles Quarles have already mentioned the possibility of tapering at some point in the future. In fact, the removal of some policy accommodation may already be priced into the bond market given that yields at the long end of the US Treasury curve have been relatively well-behaved in response to the recent higher than expected inflation data.

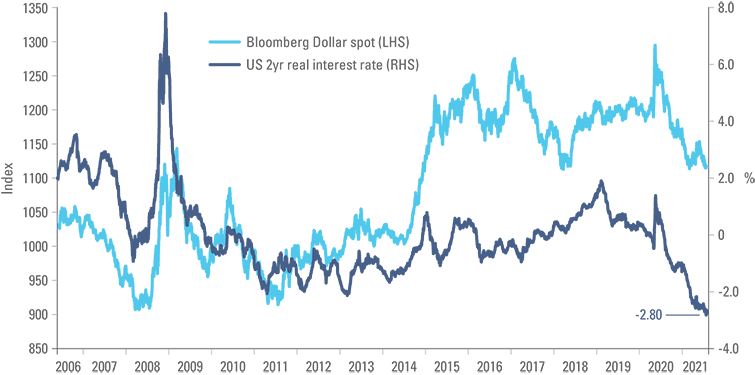

Yet, for now it seems more likely that the Fed will opt to maintain the official line that inflation is transitory. This means, in our view, that the Dollar could weaken even more than in the past 12 months (-9.2%, based on the broad Dollar index, DXY). Under rising inflation, real interest rates will decline further from already very low levels.

The current level of real interest rates in the US is already consistent with a much weaker Dollar as illustrated in Figure 8, which suggests the USD may weaken further even if real interest rates rise somewhat from here.

Fig 8: US 2 year real interest rates vs. Dollar Index (DXY)

What if the Fed decide to double-down?

If the Fed decides to go down the route of convincing its audience that inflation is transitory, a few months of elevated inflation may challenge the narrative. Furthermore, the Fed would have no choice, but to keep its asset purchasing programme if the Biden administration approves large infrastructure spending, or increases social programmes, without raising the equivalent taxes, which would lead to a more permanent elevated deficit. In this scenario, the Fed could be forced to keep expanding its balance sheet to prevent the yield curve from steepening significantly. The Fed would have little choice but to engage in yield curve control (YCC), initially covert YCC.

The Fed can, for example:

- Adjust its quantitative easing (QE) programme to buy fewer mortgage-backed securities and more Treasuries;

- Execute another 'Operation Twist', meaning selling short term bonds and purchasing long duration securities. One advantage of this policy would be that it alleviates the current scarcity of short term securities in the money market.3

- Engage in some kind of financial repression, for example by forcing local pension funds and insurance companies to add more exposure to US Treasuries in order to match their long term liabilities.

- All of the above.

If covert YCC fails, the Fed can get more explicit, for example by announcing fixed targets for yields on, 3-year or 10-year bonds. Such strategies have been adopted by the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Bank of Japan. Specific yield targets would initially allow the Fed to meet its objectives with fewer bond purchases, at least while market participants believe in the credibility of the policy.

We believe the bar for explicit yield targeting is high, not least, because by removing the escape valve of freely moving bond prices YCC is likely to cause investors to sell the Dollar aggressively.

EM central banks

In contrast with the Fed, most EM central banks facing inflationary pressures have already reacted. The Central Bank of Russia has hiked its policy rates twice from 4.25% to 5.00%, the Brazilian Central Bank increased the Selic policy rate from 2.00% to 3.50%, and the Central Bank of Turkey hiked interest rates from 8.00% to 19.00%.

Moreover, both Russia and Brazil have signalled further policy hikes. The hawkish messages are important as the currencies of these countries have been under pressure since the beginning of the coronavirus crisis, in spite of a strong boost in terms of trade, but stabilised after the rate hikes.

Weaker currencies produce upward pressure on the price of tradable goods which in turn pushes up producer prices index (PPI) inflation and possibly consumer prices. By taking measures to anchor inflation expectations early on, these central banks are avoiding pass-through of higher tradable good prices to the economy. The hawkish messaging can even actively reduce inflation by reducing the input costs of tradable goods, if the hikes allow for a nominal appreciation of their currencies.4

Not coincidently, both RUB and BRL have strengthened versus the Dollar since the central banks started to increase policy rates. TRY also strengthened until the dismissal of the central bank governor in March.

The central banks of Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic have recently signalled potential policy rate hikes to nip any inflationary pressures in the bud. In these countries, inflationary pressures are also likely to moderate due to the recent strengthening of the EUR, which tends to lift HUF, PLN, and CZK.

No need for another Taper Tantrum

A potential normalisation of monetary policy by the Fed has raised concerns about a repeat of the Taper Tantrum event of 2013. Back then the expectation of tighter US monetary policy amidst bullish growth sentiment and deflationary pressures from weaker commodity prices led to a sharply higher Dollar and major outflows from EM. The comparison with 2013 is ill-founded, however, as explained in a recent weekly publication.5 In particular, there are five important differences from 2013, which make EM economies far more resilient today:

- Real rates in the US are likely to remain low, even after an eventual U-turn from the Fed. In 2013, the 2yr break-even inflation (nominal minus real interest rates) collapsed from 2.4% to 1.0% as the hawkish Fed guidance coincided with a decline in inflation. Elevated inflation and a more cautious communication by the Fed are likely to keep real interest rates low this time.

- EM countries are running a current account surplus of more than 1% of GDP today, whereas they ran deficits of around 2% of GDP in 2013.

- EM currencies are close to their historical lowest point in both real and nominal terms, whereas valuations were relatively rich in 2013.

- Commodity prices are rising today, supporting creditworthiness, and the economies of EM commodity exporters, whereas commodities were declining in 2013.

- Foreign investor exposure to EM local markets is much lower than 2013 levels as local institutional investors tend to dominate the price action now.

Conclusion

Inflation is likely to remain elevated for the rest of the year, potentially at even higher levels than seen today, if commodity prices rise further. High headline inflation poses a clear risk to core inflation in the context of:

- Aggressive fiscal and monetary policies translating into abundant liquidity.

- Supply disruptions in industries ranging from semiconductors to shipping pushing up costs in many sectors of the economy.

- Commodity prices have more than doubled from their lows and some commodities could rise even further due to structural factors.

- The US labour force seems to demand higher wages following generous paychecks.

- The Fed maintains an extremely loose policy stance, risking an increase in inflation expectations.

The prudent policy now would be for the Fed to 'bite the bullet' and change its stance, in our view. Tighter monetary policy is unlikely to lead to a sharp increase in interest rates over the short term and the Dollar depreciation trend which started in April last year is likely to remain in place, in our view. This is not a bad environment for EM at all. They are far more resilient than in 2013, so there is no need to fear a repeat of the 2013 Taper Tantrum.

1. See https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-05-17/fed-s-clarida-says-not-yet-time-to-start-taper-talk

2. See "The 2021 Outlook: Seven themes for a post-vaccine world", The Emerging View, 17 December 2020.

3. See https://www.marketwatch.com/story/why-demand-for-feds-reverse-repo-facility-is-surging-again-11621904689

4. Most EM central banks are now highly credible. In most EM countries, pass-through inflation is a myth. See https://www.ft.com/content/a52e621e-3407-11e7-99bd-13beb0903fa3

5. See "EM unlikely to be at risk of another 'Taper Tantrum' episode', Weekly investor research, 22 February 2021.