Since the Covid shock, high global inflation, aggressive US fiscal expansion and a strong dollar have created a challenging environment for Emerging Market (EM) countries.

Unsurprisingly, in the year following the outbreak of Covid, nearly all EM sovereign credit rating actions were negative. However, since then, EM debt has outperformed, despite a difficult backdrop as, under the hood, fundamentals have been improving. May 2024 was the twentieth successive month in which EM has surpassed Developed Markets (DM) in both manufacturing and services Purchasing Manager Indices (PMIs). This comparative strength in economic activity can also be seen in the hard data. GDP in EM economies surprised to the upside in 2023, growing 4.3% versus just 1.6% in DM. The IMF expects similar numbers this year.

Coupled with higher growth has been better inflation dynamics. Most EM economies have brought inflation down more quickly than their DM counterparts. These trends were the foundation for calling the EM asset class ‘resilient’ in our 2024 outlook, and they continue to play out as the year progresses.

Finally, several smaller Frontier Market (FM) countries that lost market access or defaulted post-Covid have since implemented structural reforms and either restructured or are in the process of restructuring their debts. As a result, their credit ratings have been on a virtuous upgrade cycle.

Positive momentum in credit ratings

The improvement in EM growth and inflation fundamentals is not purely a cyclical story. It has been supported by a wave of structural economic reforms, including in Brazil, Indonesia, India, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Saudi Arabia. The combination of better data and positive reforms has driven a wave of upgrades in EM sovereign credit ratings in the last two years. These upgrades have come despite global macro headwinds, including 10-year US Treasury yields moving from 0.5% to 5.0%, and Chinese economic growth slowing faster than expected.

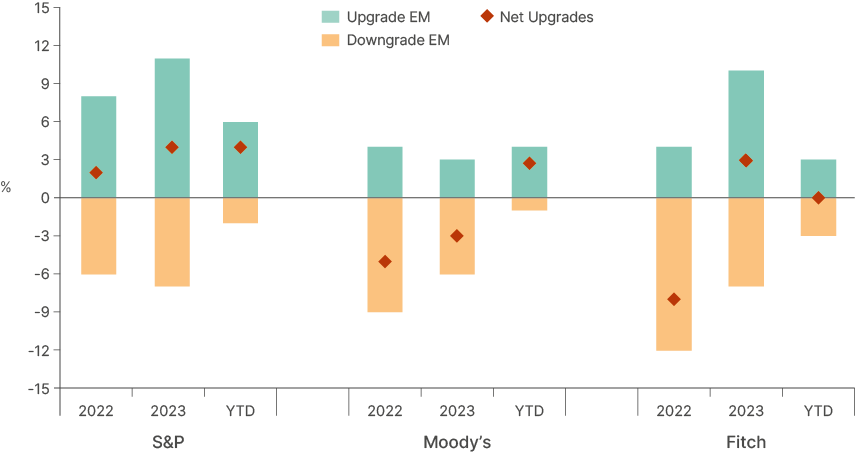

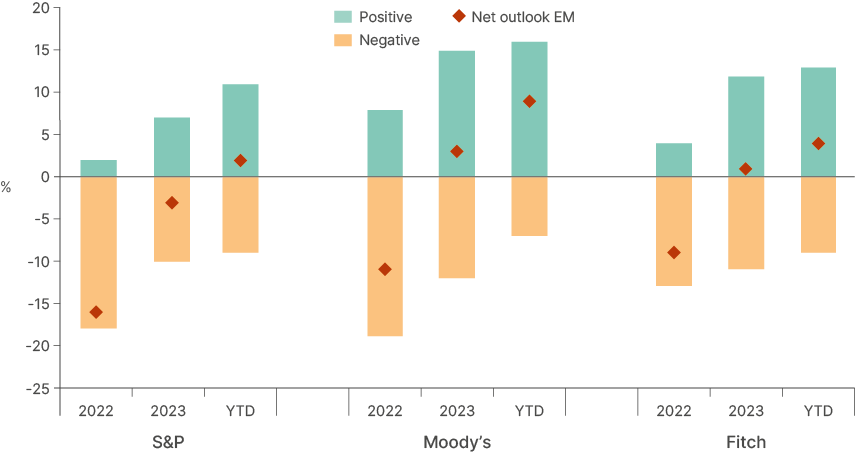

Standard & Poor’s has been leading the re-rating process, with more upgrades than downgrades in 2022, 2023, and year-to-date, as per Fig 1. Moody’s has been more conservative, downgrading more countries than it upgraded in the previous two years, but is catching up in 2024. Fitch had the largest number of downgrades in 2022, but flipped to upgrades in 2023 as well. This improving trend is likely to have more legs, in our view. The forward-looking outlooks for EMs reflect this, turning positive on a net basis across the three rating agencies this year (Fig 2).

Fig 1: Number of EM Upgrades vs. Downgrades 2022, 2023 and YTD, by Rating Agency

Fig 2: Outlook by Rating Agency

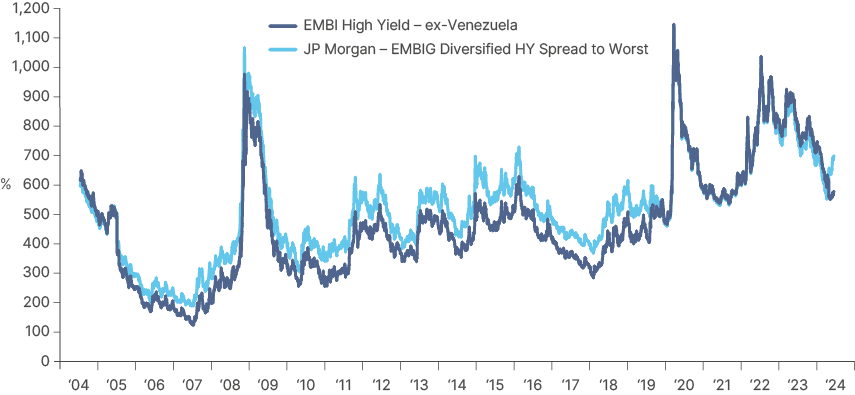

Good sovereign credit ratings and positive outlooks are not just nice to have, they have a meaningful effect on a country’s cost of debt over the medium term. Fig 3 shows the significant 500 basis points (bps) drop in credit spreads on the JP Morgan EMBI High Yield Index (ex-Venezuela) since July 2022. While credit spreads remain at very elevated levels by historical standards, several countries have regained access to markets during the period, coinciding with net ratings upgrades amongst index members..

Fig 3: EMBI High Yield and EMBI HY ex-Venezuela Spreads

Despite credit ratings giving credence to the macroeconomic outperformance observable in EM today, this strength has not yet been fully reflected in capital allocations to EM assets, in our view. This is particularly notable in the comparison between flows to EM and US assets, which have absorbed one-third of the global cross-border capital flows since Covid.1 This hoovering up of international capital has been driven by pro-cyclical fiscal spending and high interest rates supporting the Dollar. However, as US debt fundamentals become increasingly overstretched, and the US Federal Reserve (Fed) approaches its first cut, both drivers may be about to stall or even unwind. In contrast, the wave of EM upgrades is being driven by improving debt metrics, and shrewd economic reforms that will help lay the foundation for sustainable growth.

Themes driving the turnaround

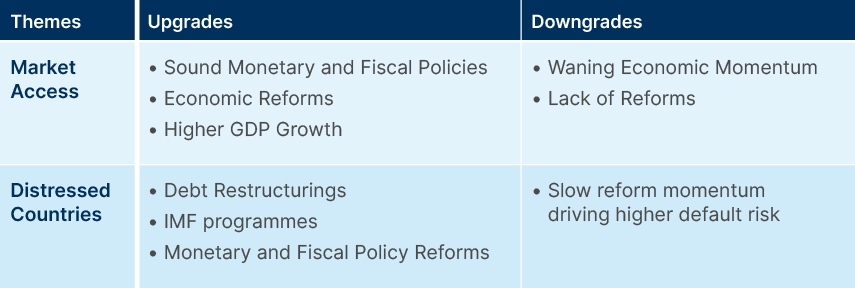

Four key themes are present in countries subject to rating actions, leading to lower funding costs for countries with market access and renewed market access to distressed countries.

1. Better fundamentals

For most countries with access to debt markets, ratings upgrades have been driven by prudent fiscal and monetary policy bringing down inflation early, leading to lower rates, better growth and improved external accounts and debt profiles. For upgraded Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) sovereigns, higher oil prices have supported revenues, while efforts to diversify their economies have started to pay off, allowing for fiscal consolidation and a better debt sustainability outlook. These improvements are shown in selected debt sustainability measures in Fig 5.

2. Economic reforms

Several countries have been implementing meaningful economic reforms. Those include Brazil, India, Indonesia, Oman, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia. Reforms accelerated across EM after the difficulties of the Covid and post-Covid period, including in Argentina, Pakistan, and Türkiye.

3. IMF programmes

Many low-rated frontier countries are benefitting from International Monetary Fund (IMF) programmes, improving debt sustainability and investor confidence. IMF programmes are typically linked to economic reforms with the objective of regaining access to capital markets. More recently, the IMF has requested debt restructuring as a condition for disbursements in low income-countries with poor debt sustainability dynamics.

4. Debt restructuring completions

Numerous countries without market access (poor credit metrics leading to distressed bond price levels) have been completing debt restructurings which, coupled with structural reforms, are enabling a more sustainable debt profile. This mix of higher economic growth tailwinds and idiosyncratic recovery stories in the high yield space creates a good environment for active EM investors, with pockets of diversified opportunity across different regions.

Fig 4: Themes driving upgrades and downgrades

Forward-Looking Rating Trends and Outlooks

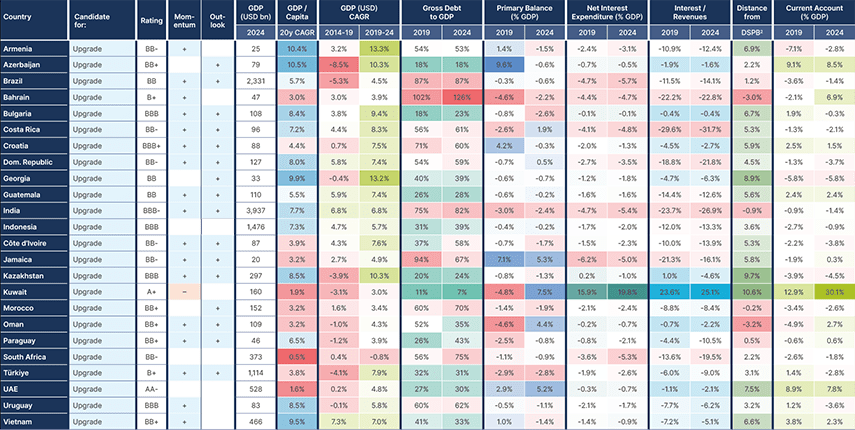

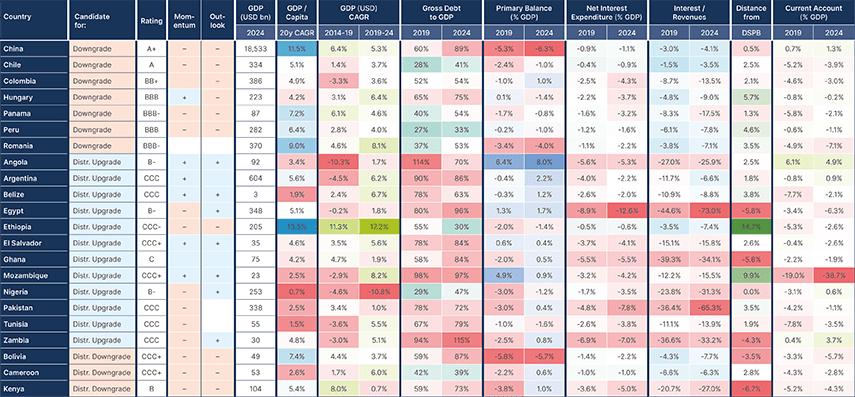

Across the EM universe, there are 28 countries with either positive rating momentum (have been upgraded within the last two-years) or a positive outlook by at least one of the three rating agencies. There are just nine countries with a negative outlook or negative momentum by at least one rating agency.

Fig 5 shows each of these countries along with selected macroeconomic data measuring debt sustainability. There are seven additional countries (Indonesia, Kuwait, South Africa, UAE, Ghana, Pakistan, and Tunisia) which are more likely to be upgraded than downgraded next, in our view, given their progress in key data points and political developments. On the other hand, Romania, which doesn’t have a negative outlook, could be in danger of an impending downgrade, given its macro indicators.

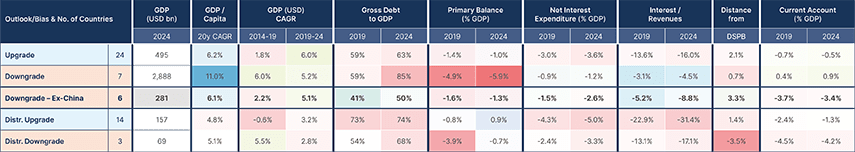

Fig 6 shows a weighted average (by GDP) of datapoints for countries which have seen positive action vs those which have seen negative action.

Key findings:

- GDP growth improved significantly more in countries that have been upgraded and/or have positive outlooks, than in countries that are downgrade candidates.

- The ratios of net interest expenditure to GDP and debt to GDP have increased to a much lesser magnitude in countries that are candidates for upgrades.

- The ‘upgrade candidates’ have better external account dynamics. Importantly, these countries have improved their primary balance, helping to compensate for higher interest costs.

Fig 5: Selected Credit Metrics for Countries with Positive vs. Negative Outlook

Fig 5 (continued): Selected Credit Metrics for Countries with Positive vs. Negative Outlook

Fig 6: Number of Countries with Positive vs. Negative Outlook & Selected Credit Metrics

The aggregate data doesn’t do justice to the dramatic fundamental improvement of the many individual countries. Brazilian GDP growth, for example, improved from -5.3% from 2014-19 to +4.5% from 2019-24, as highlighted in Fig 5, thanks to structural reforms implemented by presidents Michel Temer and Jair Bolsonaro. Other countries with large improvements in their GDP growth profile, a key factor to stabilise the debt dynamics, were Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Türkiye, Angola, Argentina, Mozambique, Tunisia, and Zambia. On the other hand, GDP growth deteriorated sharply in Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana, Pakistan, Armenia, Panama, Colombia, and China. These growth deteriorations will raise the likelihood of rating downgrades if these countries do not implement economic or monetary reforms in response.

Improving fundamentals in Central America

Credit ratings and outlooks have improved in multiple Central American countries, with sound fundamentals across the region backed by positive policy reforms. Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, and Guatemala were each upgraded once in 2023, and Costa Rica again in 2024. This double-upgrade was based on a very strong recovery in GDP (5.4% in 2023), along with an ongoing commitment to a strict fiscal anchor that caps growth in government expenditure while debt/GDP is above 60%. This framework helped bring the ratio down to 61% in 2023, from 68% two years prior.

According to the Dominican Republic’s Minister of Finance, the country is targeting an investment grade rating following Fitch’s outlook change from BB stable to BB positive in November 2023. A consistent record of robust economic growth, as well as significant institutional advancements, have improved confidence in the country’s positive trajectory. Guatemala was upgraded to BB by Fitch and S&P in early 2023 for similar reasons; along with tax reforms leading to collections rising from 10.7% of GDP in 2019 to 12.1% in 2022.

The Gulf Cooperation Council

Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Oman have all also seen positive rating action since the pandemic. These oil exporters have fixed fuel and electricity prices as well an abundance of migrant workers, two economic factors that kept them insulated from a significant portion of the inflationary pressures felt so keenly by the rest of the world. Hydrocarbon dependence is a drag on the region’s credit ratings due to acute exposure to energy price cycles. However, the GCC has benefitted from higher commodity prices post-Covid, and therefore avoided the need for the deficit-inducing fiscal stimulus that has contributed to ‘sticky’ inflation in the US and Europe.

Qatar’s upgrade to AA in March 2024 was driven by a sharp reduction in gross debt/GDP from 72% in 2020 to just 39% in 2023 (net debt is negative), along with sustained fiscal surpluses and a rapidly expanding GDP per capita as their LNG exports rise, and their migrant workforce becomes more sophisticated. Saudi Arabia’s upgrade to A+ in 2023 reflects formidable fiscal and external balance sheets, In Oman’s case, an upgrade to BB+ was backed by a rapid decline in government debt from 68% in 2020 to 36% in 2023. The Omani authorities also plan to lower the share of USD debt as the local market develops and will partially refinance external debt maturities in rial.

Structural reforms increasing GDP growth potential

While a clear positive trend in debt sustainability fundamentals is often needed to improve credit ratings, outlook changes by the rating agencies can be driven by reforms that lay the foundation for future fundamental improvement. Across the Emerging Market universe, a variety of exciting reforms are taking place with the potential to increase the growth potential and creditworthiness of some major economies.

India, for example, a star performer in equity markets over the last two years, was upgraded by S&P to a positive outlook in April. The government’s elevated debt and interest burden prevented a credit rating upgrade, according to the agency. However, economic reforms and larger infrastructure investments are brightening the outlook for long-term, sustainable growth. Poor infrastructure, in cities but also across transport networks and ports, is often cited as one of the principal barriers to the expansion of India’s economy, particularly its manufacturing sector. The government has been addressing this issue and has ambitious plans to improve this further, with USD 1.4tn in infrastructure investment budgeted from 2020 to 2025.

Major policy reforms in Türkiye have led to both an upgrade in credit rating to B+ from Fitch, and a positive outlook affirmed in March. This is principally due to the pivot in macroeconomic policy in June 2023. Prior to this, Türkiye’s President Tayyip Erdoğan had strongly opposed rate hikes, even as inflation soared to over 80% and the Lira plunged to all-time lows. However, after his re-election, Erdogan ended his crusade against high rates, and the central bank hiked aggressively from 8% to 50% by March 2024. Fitch attributed the upgrade to “increased confidence in the durability of policies implemented since the pivot in 2023”, and the positive outlook to its expectation that inflation should continue to decline. While the path won’t be a straight line, Türkiye is a strong candidate for multiple upgrades, with a decent chance of regaining investment grade by the end of the decade, in our view.

Constructive reform momentum has also led to positive outlooks for Nigeria, Ivory Coast, and Morocco year-to-date. In Nigeria, reforms over the last year include adjustments to distorting monetary and foreign exchange (FX) policies, as well as improved coordination between the central bank and Ministry of Finance, which has resulted in the return of significant inflows to the FX market. Morocco’s upgrade to BB+ positive by S&P reflects the country’s commitment to socioeconomic reform, as its economy becomes increasingly competitive and dynamic. Ivory Coast broke sub-Saharan Africa’s nearly two-year lockout from international capital markets this January by selling USD 2.6bn in Eurobonds. Fast GDP growth, (IMF estimates 6.5% in 2024) driven by rising commodity exports are leading to improvements in external and fiscal imbalances that are expected to continue, hence the move from S&P and Moody’s to turn their outlooks positive.

Debt-restructurings getting Frontier back on track

Debt restructuring efforts backed by IMF support have historically preceded credit-rating upgrades and a return to market access for distressed nations. Argentina and Ecuador are recent examples, with Argentina restructuring USD 65bn in external debt in 2020, leading to a credit rating upgrade from selective default (SD) to B-, and Ecuador restructuring USD 17.4bn in bonds in the same year, resulting in the same. This month, Zambia completed debt restructuring negotiations with the assistance of a USD 1.4bn IMF credit facility, signalling a potential path towards an upgrade from its CCC rating. Particularly within EM, IMF assistance is often critical to help manage debt burdens, extend repayment periods, and lower debt service costs – all actions that strengthen fiscal resilience, restore macroeconomic stability, and boost investor confidence.

Therefore, ongoing IMF-supported debt restructuring negotiations in countries such as Ethiopia, Ghana, and Sri Lanka, highlight a promising trend. These nations are navigating their own debt challenges with the aim of stabilising their economies and restoring creditworthiness. As these countries progress with their restructuring efforts, we can anticipate more future credit rating upgrades and fewer distressed frontier sovereigns.

Downgrade Risks

While negative rating actions have been scarcer in emerging markets over the past 18 months, some countries have seen their forward-looking outlooks turn negative. Factors driving negative outlooks seem to be mostly contained within individual economies. China’s outlook was downgraded to negative by Fitch in April, as the country continues to struggle with a beleaguered property sector driving poor consumer confidence and rising government debt, which is forecast to reach 89% of GDP in 2024, from 60% in 2019. Fitch forecasts GDP in China to moderate to 4.5% in 2024 from 5.0% last year, citing property sector weakness and subdued household consumption.

Nevertheless, the stronger-than-expected decline in Chinese GDP growth is having only a mild impact across the broad EM universe, as policy development within countries has been the primary driver between good and poor performers. For example, Colombia’s negative outlook revisions from S&P in the last six months reflect weaker growth (1.3% estimate 2024) and low private-sector investment, while Chile’s new negative outlook is a consequence of political volatility in the last three years which has led to a stagnation in reforms that would improve its economic and fiscal prospects.

Panama was recently downgraded by Fitch due to concerns over the impact of ongoing controversy around the closure of a large copper mine on potential GDP growth, fiscal accounts, and investor confidence. Weaker revenues and higher deficits have also led to a significant rise in debt/GDP since 2019. South Africa, with low GDP and high unemployment, would be another downgrade candidate, but the Unity Government formation is an encouraging development which may deliver badly-needed structural reforms. Should these materialise, the country could well be a candidate for upgrades, in our view.

What About Developed Market Ratings?

Versus EM, we see fewer positive stories playing out today in Developed Markets. Artificial intelligence (AI) mania is driving another leg of the extended bull run in the US stock market. However, for the last ten years the US government has been propping up the economy with large pro-cyclical fiscal deficits, which is driving the debt burden ever higher. Existential talk among market participants around the fate of the Dollar is intensifying as a result. This year, America’s debt service cost is forecast to overtake both its defence and Medicare budgets, with an estimated 3.1% of GDP to be spent on interest payments, up from 1.6% in 2020. In 2023, Fitch downgraded the US debt rating from AAA, reflecting the expected continuation of fiscal deterioration over the coming years.

On the other side of the Atlantic, high debt/GDP ratios and sputtering growth have left many European economies increasingly fragile, including Germany, France, and the UK. Earlier in June, S&P downgraded France’s credit rating to AA-, citing expectations that higher-than-expected deficits would continue to raise debt ratios in the Eurozone’s second-biggest economy (Fitch had downgraded the sovereign a year prior). With the French election bringing the looming uncertainty of a far-right government, Moody’s may follow suit and downgrade its Aaa (equivalent to AAA) rating.

Israel is another sovereign at risk of further downgrades, due to higher defence spending resulting from the war with Hamas. Although some index providers have Israel as an Emerging Market, the country is deemed a Developed Market by MSCI and is not part of the JP Morgan Emerging Market Index family.

1. See – https://www.fa-mag.com/news/how-the-u-s--mopped-up-a-third-of-global-capital-flows-since-covid-78491.html

2. See – DSPB stands for Debt Stabilising Primary Balance. It’s the difference between nominal GDP growth and net interest expenditure as % GDP plus the primary balance as % GDP. For nominal GDP growth, we’ve considered the lower between LC and USD nominal GDP growth for distressed countries and LC GDP growth for countries that can finance all its liabilities in LC.

Conclusion

The recent wave of positive action by ratings agencies in EM corroborates a clear trend of improving fundamentals and solid policymaking. We expect this pattern to continue, considering there are significantly more countries with positive outlooks than negative ones. Furthermore, several debt restructurings are in the process of being concluded, which should bring further upgrades. This positive trend in EM credit ratings contrasts with DM where fundamentals are deteriorating. Yet, most investors continued to pour capital into the US, a country where the fundamentals and valuations are increasingly stretched. This creates a dislocation in the markets and an opportunity, in our view. As the trajectories of developed and emerging economies continue to diverge, investment flows are likely to follow, driving better risk-adjusted returns in EM. In fact, returns have already turned, with EM corporates and sovereigns outperforming DM over the last five years and EM high yield outperforming DM over the last two.