The Russo-Ukrainian war is one of, and perhaps the most consequential conflicts since the end of World War 2. We examine the events on the ground, the announced sanctions and a first take on its potential impacts, both intended and unintended.

Emerging markets

Russo-Ukrainian war

Last Wednesday Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The attack started with air bombardment of “military facilities” before a three-front invasion via Crimea, Donbass and Belarus. Ukraine initially had limited ability to deal with the Russian airstrikes on a largely flat land – a key geographical weakness – and decided to retreat to cities where its military may hold an advantage in militia-style warfare. The Russian army has encircled Kharkiv and Kyiv and managed to control some territory in southern Ukraine next to Crimea. Some expected this to be a quick war, but the news from the ground suggests otherwise after the Ukrainians managed to hold key strategic cities after five days of fighting.

Drones imported from Turkey are inflicting severe pain on Russian forces. The Ukrainian army has received support from tens of thousands of reservists and civilians taking up weapons and fiercely resisting Russia’s advance.

Encouragingly, Germany broke its long neutral stance on military conflicts and started supplying weapons to Ukraine. Germany said it would send 1,000 anti-tank weapons and 500 Stinger anti-aircraft defence systems to Ukraine. Chancellor Olaf Scholz gave an emotional speech in the Bundestag on Sunday saying that Germany will accelerate the construction of two port facilities for liquid natural gas imports and raise military spending to more than 2% of its GDP for the foreseeable future, which is consistent with its NATO commitment.

Earlier in the weekend, Turkey signalled it could block the Russian navy’s access to the Black Sea after acknowledging the situation turned into a war, citing the possibility of applying the provision of the 1936 Montreux Convention which gives Turkey control over the two straits that connect the Mediterranean to the Black Sea via the Sea of Marmara.

Ukrainian President Volodymir Zelensky posted a video in Russian condemning the attacks and asking the Russian population to do whatever they can to motivate their leaders to stop the aggression. Zelensky remained in the country, posting daily videos from Kyiv where he pledged to fight Russia and defend his nation. Millions gathered across the world to protest against Russia’s invasion and thousands were arrested in protests in Russian cities. On Sunday, Ukraine agreed to send a delegation to Belarus to negotiate a potential cease-fire with Russia. The United Nations said that 368,000 refugees have left the country since the beginning of the conflict until Sunday.

Sanctions

In response to the Russian attack, the West announced the most severe round of economic sanctions ever dealt to a significant commercial partner, which includes:

- Stopping US financial institutions from offering correspondent banking relationships to all major Russian commercial, industrial and policy banks;

- Severing selected banks from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT);

- Freezing the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) foreign exchange (FX) reserves;

- Banning European and US investors from buying new debt issued by Russia, its banks and corporations. Albeit no sanctions imposed, so far, on holding positions in existing securities;

- Sanctions on individuals, including President Vladimir Putin and his inner circle, including many oligarchs and foreign secretary Sergei Lavrov; and

- Banning Russian aircraft from using European and British airspace.

Impact of sanctions

The sanctions are extremely disruptive as they make it very difficult for financial and commercial transactions to settle in the USD system. The RUB depreciated around 30%, from RUB 82 per USD on Friday to above 105 in early trading today. A significant amount of financial and commercial transactions may fail due to the inability of Russians banks and corporations to transact in USD via the correspondent banking system and SWIFT systems.

Russian individuals fearing inflation rushed to withdraw money from the banking system as well as spend RUB on luxury and durable goods to avoid a significant loss of purchasing power. These actions tend to destabilise the financial system and increase inflation at the same time.

The impact in the Russian financial system is magnified by sanctions freezing assets from the CBR. The central bank will not be able to sell its USD or EUR, held in the US and EU banking systems, making it harder to defend the RUB. The CBR is also likely increase liquidity provisions in the system to avoid a systemic crisis as depositors increase withdrawals. Earlier today the CBR more than doubled its policy rate, hiking it by 1,050 basis points to 20%, saying that external conditions drastically changed and the rate hike was necessary to make deposits attractive. Injecting liquidity when the RUB is in a vicious spiral and the central bank is increasing interest rates seems like a contradiction, but will be necessary to avoid a potential banking crisis.

Nevertheless, the CBR has prepared for a significant crisis for a number of years, diversifying its reserves from USD securities. Today, more than 20% of the reserves are held in gold and the remainder are spread across other markets with less than 10% of FX reserves in USD.1 Gold may play an important role in sustaining Russia’s essential external transactions – for example, gold may be swapped against (or sold for) currencies from countries not participating in the sanction regime.

Unintended consequences

There are also several unintended consequences from sanctions. Some will only be clear after several days or weeks, depending on the duration of the war and for how long the sanctions remain.

The first is the risk of a massive liquidity shock in the global financial system. Last week several banks stopped accepting Russian assets as collateral, leading to disorderly unwinding of existing positions across capital markets. The inability of Russian banks to transact with the world, due to the severance of correspondent banking relationships now raises counterparty risks that did not exist two weeks ago.

The Bank for International Settlements reported Russian banks had USD 1.38trn of existing claims to local investors, of which USD 142bn was in foreign currencies in Q3 2021. In addition, Russia had USD 201bn of cross border claims (USD 172bn in foreign currencies) and USD 134bn of cross border liabilities (USD 63bn in foreign currencies).2 If Russian banks cannot recover their claims or pay their liabilities to the rest of the world the global financial system may experience shockwaves of liquidity events (since unpaid transactions beget more failures), potentially leading to a liquidity crisis compared with the liquidity shock in March 2020 or even the default of Lehman Brothers in 2008.

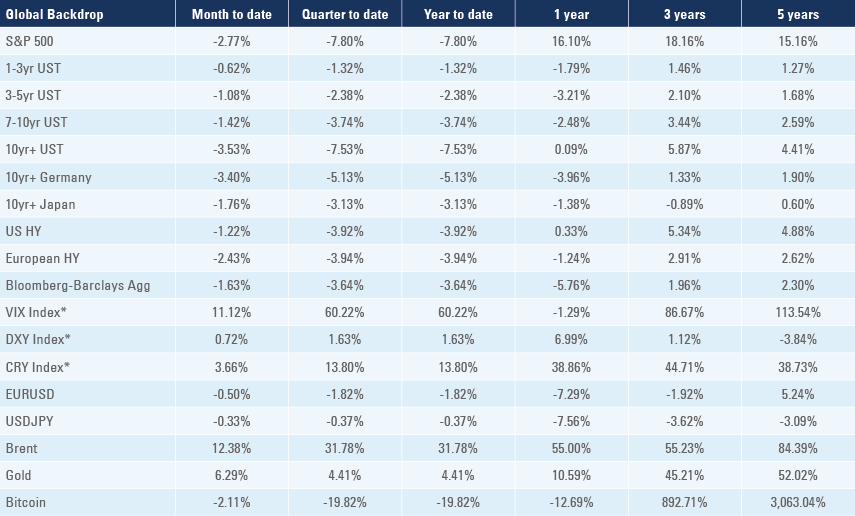

Such liquidity shock will have a significant impact on global activity when the world is healing from the pandemic crisis amidst elevated inflation, which will deteriorate further due to the conflict. The US Federal Reserve (Fed) and other global central banks may have to offer liquidity via swap lines to international counterparties, injecting liquidity in the system one month before the planned first policy rate increase by the Fed in March and a few months earlier than the intended start of the unwind of its balance sheet.

Another unintended consequence will be the willingness for countries to diversify their exposure from the western financial system. The “weaponisation” of the USD and EUR financial systems inflicting a severe blow against a large country with significant commercial ties to the West may bring more countries to adopt Asian currencies, including the RMB, as part of their FX reserve diversification, weakening the ability of governments to implement similar measures in the future.

The nuclear threat

When the UK banned Aeroflot from its aerospace, Russia responded in kind, banning British Airways and any other UK flights from utilising the Russian aerospace, a major inconvenience for intercontinental flights given the sheer size of the Russian territory.

However, after the US and Europe announced the major financial sanctions above alongside banning all Russian aircraft from European airspace, Russia did not retaliate. Instead, Putin put Russian nuclear forces on high alert.

This is a ominous moment akin to the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 when the world stayed on permanent high alert for the risk of the use of nuclear weapons deployed in a military conflict. This is a truly existential threat to human kind, an issue that is very hard to prepare for or even price in financial assets.

Furthermore, Russia breaking the 1994 agreement between US, Russia and Ukraine, in which Ukraine agreed to give up its nuclear weapons in exchange for a promise against aggression, was a watershed moment. From today, any nation that feels its political regime or society are under threat will have a reason to believe that it would only be safe if it had nuclear weapons, significantly increasing the risk of rogue regimes acquiring them.

Inflation

Another unintended consequence of the financial sanctions is supply shocks. If Gazprom cannot receive payments, then it may have no alternative but to stop supplying natural gas to Europe. To be clear, all sanctions so far were carefully implemented to ring-fence the energy system. In fact, Russia ordered Gazprom and other large corporates to sell their foreign currency held on their balance sheets to the market (they still can transact in EUR) in order to support the RUB. Nevertheless, the willingness of Germany and other EU countries to diversify away from Russia will lead to more demand for liquefied natural gas (LNG), putting pressure on an already tight energy market.

Furthermore, Russia and Ukraine have a significant market share of agricultural products. Combined, these two countries exports more than 50% of sunflower seeds, close to a quarter of wheat, barley and linseeds, as well as close to 15% of corn and fertilisers. This is likely to put pressure on global food prices, as large importers of these food items, such as Egypt and Turkey, will seek alternative suppliers if they cannot import from Russia due to the sanctions.

Russia and Ukraine also export a significant amount of components to the semiconductor industry with more than one-third of global palladium exports and close to 90% of US semiconductor-grade neon. The two countries are also large producers of industrial metals such as aluminium, steel and iron ore. Should the conflict persist, the war effort of producing more machinery may lead to increased demand at time when global supply chains remain disrupted.

Perhaps most importantly in the short term, a significant disruption to the global financial system, demanding broad-based liquidity injections by central banks, would take place at a time when liquidity was excessive and part of the broad inflationary problem. Aggressive liquidity injecting leading to a deterioration the current inflationary spiral is a small, but non-negligible risk.

The impact on Emerging Markets

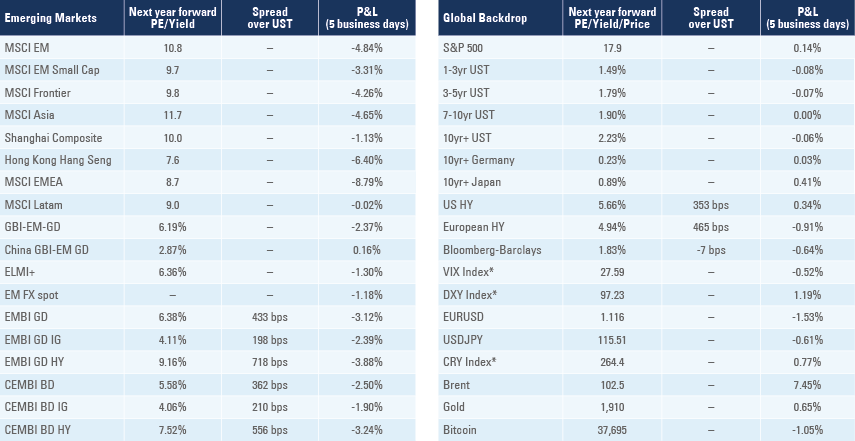

The price of Russian and Ukrainian assets suffered a significant blow from the conflict. The aggressive Russian actions raises the risk of this market becoming “uninvestable”, due to sanctions or governance/moral reasons, for foreign investors from western countries, notwithstanding Russia’s stockpile of reserves.

For Ukraine, the risks of regime change and a significant disruption to the country’s infrastructure and economy will affect the willingness and ability to pay in ways that will only be clear when the conflict is over.

Asset prices from both countries will reflect the severe uncertainty, experiencing high volatility depending on the events on the ground. Asset prices may rise sharply for example, should the discussions in Belarus lead to a cease-fire or a credible de-escalation path.

The conflict will lead to spill overs to emerging markets. For example, the shares of companies exporting products to Russia (e.g. Brazilian protein companies) sold-off last week as higher wheat and corn prices increases costs, while the sanctions disrupt sales.

However, Russia and Ukraine are relatively small markets for most EM countries, making the trade linkage impacts mild. The most directly exposed countries are in Eastern Europe and broader Eurasia as Ukraine and Russia imported c. USD 9.0bn of goods from Poland and USD 7.5bn from Turkey in 2020.

Importers of energy will suffer the impact of higher energy prices, and the ones with high foreign currency debt and low FX reserves, such as Sri Lanka and Turkey, are the most vulnerable. However, the main risk for EM assets emanates from the unintended consequences of the sanctions to the global financial system.

On the other hand, higher commodity prices will support commodity-exporting countries, primarily in the Middle East, Latin America and Africa. The commodity-exporting regions were already benefiting from higher commodity prices and the geopolitical-induced commodity prices will provide significant tailwinds for the region, except for the scenario where the current conflict escalates further and leads to a global economic recession.

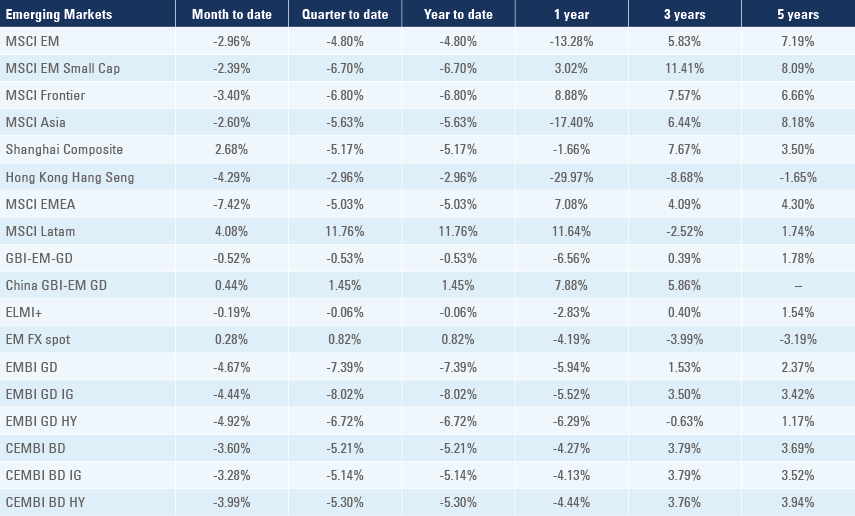

If the worst is avoided, the current event is likely to provide an opportunity for EM investors with severe dislocation across asset prices. Importantly, EM local currency markets have been relatively resilient with EM FX selling off only 1.2% last week, in line with the advance of the USD index. The resilience of EM currencies is due to high levels of FX reserves, high interest rates and an increase in terms of trade against the backdrop of weak currencies.

Snippets

- Brazil: CPI inflation rose 1.0% in the first 15 days of February, 10bps above consensus and 40bps above the January number, taking the yoy rate 0.6% higher to 10.8%.

- Czech Republic: The yoy rate of PPI inflation surged to 19.4% in January from 13.2% yoy in December, significantly above consensus, led by energy and electricity prices.

- Hungary: The National Bank of Hungary hiked its policy rate by 50bps to 3.4%, in line with consensus.

- Malaysia: The yoy rate of CPI inflation dropped 0.9% to 2.3% in January.

- Mexico: The yoy rate of real GDP growth rose 0.1% to 1.1% in Q4 2021, while CPI inflation rose 0.2% to 7.2% yoy in the first 15 days of February. The yoy rate of retail sales declined by 0.5% to 4.9% in December (consensus 6.0%) while the trade balance moved to a USD 6.3bn deficit in January from a USD 0.6bn surplus in December, significantly below consensus.

- Poland: The yoy rate of retail sales rose to 20.0% in January from 16.9% yoy in December.

- Russia: The yoy rate of industrial production rose by 2.5% to 8.6% in January, ahead of consensus.

- South Korea: The Bank of Korea kept its policy rate unchanged at 1.25%, in line with consensus.

- Taiwan: The yoy rate of real GDP growth was unchanged at 4.9% in Q4 2021.

- Thailand: The yoy rate of real GDP growth rose 1.9% in Q4 2021 from -0.2% in the previous quarter.

Developed markets

US: The Markit Manufacturing PMI rose 0.5 to 56.0 in February, disappointing consensus by 1.5 points. The University of Michigan sentiment was unchanged at 61.7. Durable goods orders rose 1.6% in January (1.0% estimate) after increasing 1.2% in December (revised from -0.7%). Personal income was flat and personal spending rose 2.1% in Q4 2021.

EU: The Eurozone Manufacturing PMI was unchanged at 58.7 in February, slightly above consensus.

1. See https://twitter.com/elinaribakova/status/1496718116730159105

2. See https://www.bis.org/statistics/bankstats.htm?m=6_31_69