Investor interest in Qatar is typically cyclical in nature and has focused on the outlook for global liquified natural gas (LNG) and, more recently, the hosting of the 2022 FIFA World Cup. In many ways, with justification. The country’s dominant growth driver for two decades has been LNG, now responsible for 20% of global export supply, and the World Cup saw an approximate USD 300bn investment programme spanning a decade.

However, is such a mindset short-sighted?

Qatar’s National Vision 2030 is leading to structural reforms that can profoundly enhance its institutions, the ease of doing business and the operating environment for its corporates. There already exists an attractive ‘all cap’ Qatari investable universe comprising a range of stock opportunities that often yield high dividends. Many of these companies benefit from production cost advantages, and favourable terms and monopolistic positions in industries that the Qatari government has prioritised for growth. This is taking place in tandem with significant capital market development triggering the potential for a positive ‘liquidity shock’ and a sharp re-rating of equity multiples.

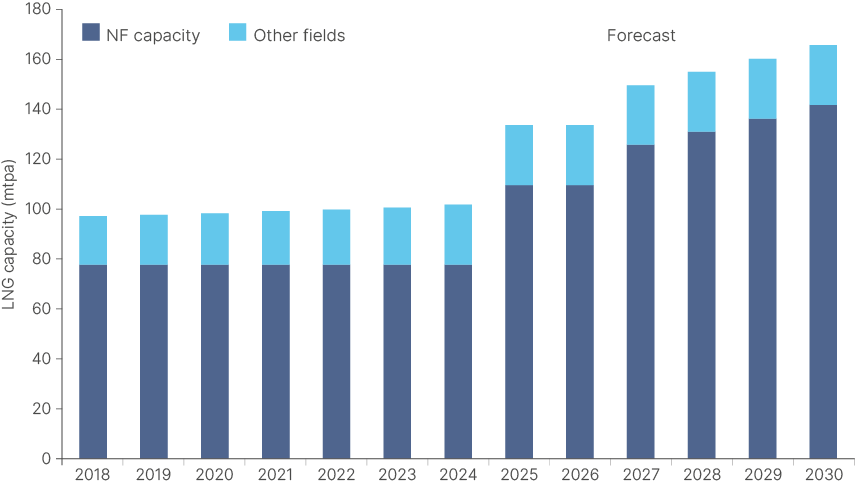

Such an attractive trajectory is also well underpinned. Qatar is already the largest global LNG producer, yet it is on the verge of expanding its capacity by over 60%, which could transform its economic fortunes. LNG production typically benefits from long dated, stable and recurring contracts. The gas is also seen as the ‘go-to’ decarbonisation transition fuel. This means demand growth for the gas is much more ‘structural’ in nature than oil. Consequently, the quality of the backing of Qatar’s economy, as well as the financing of its diversification programme, is second to none.

This paper assesses the investment opportunity in Qatar.

1. The economic roadmap

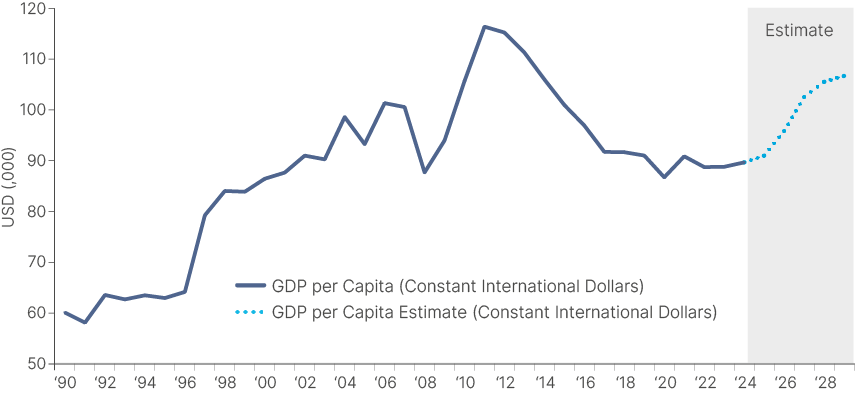

Towards the end of the 1990s, Qatar saw a step-change in the magnitude and sustainability of its economic growth based on a competitive LNG value chain with global reach. Qatar succeeded in scaling up, integrating downstream and building a reputation as a reliable and flexible partner and supplier. The period saw a significant increase in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita with Qataris becoming one of the wealthiest societies in the world. GDP growth settled at around 4-6% in the 2010s, before being tested during the 2017 diplomatic dispute and the pandemic. Domestic economic resilience was demonstrable, surprising many in the market, and the economy soon rebounded.

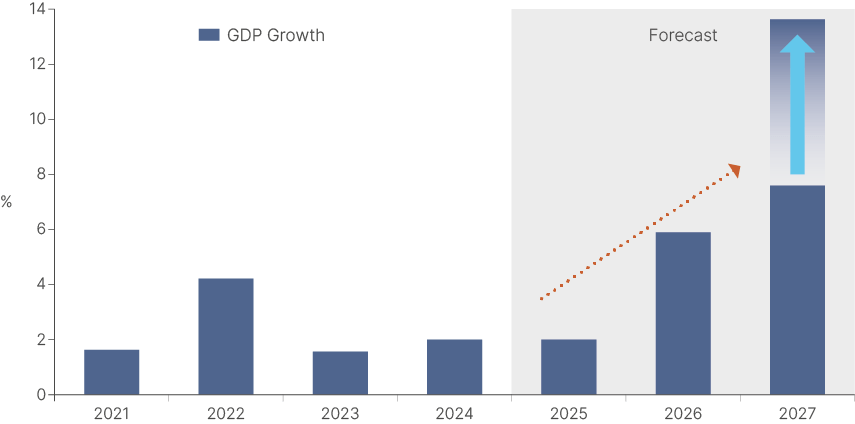

The build-up to, and hosting of, the World Cup saw a huge public infrastructure investment programme incorporating ports, roads, rail, airports, as well as stadiums. This delivered economic growth of over 4% in 2022. Some sectors of the economy have since needed to undergo a period of ‘digestion’ for a project of this scale. Bank non-performing loans increased, while lower economic activity and property oversupply weighed on real estate prices and rental yields. This has all weighed on economic growth. However, looking near term, Qatar appears to be on an improving path and growth expectations are being revised up. As we look forward to 2025 and beyond, the prospect for Qatar’s LNG production to multiply (see North Field Expansion in Section 3) means Qatar’s real GDP growth should accelerate, on a conservative basis, to 7-8% in the near term, with some economists forecasting a much more significant leap higher.

Fig 1: Qatar GDP growth

Fig 2: Qatar GDP per Capita

2. Qatar’s vision

Meanwhile, Qatar’s National Vision 2030, launched in 2008, is focused on diversifying away from a state-led and hydrocarbon-dependent growth model. A private sector-led, ‘knowledge-based’, and greener economy is seen as much more attractive and sustainable.

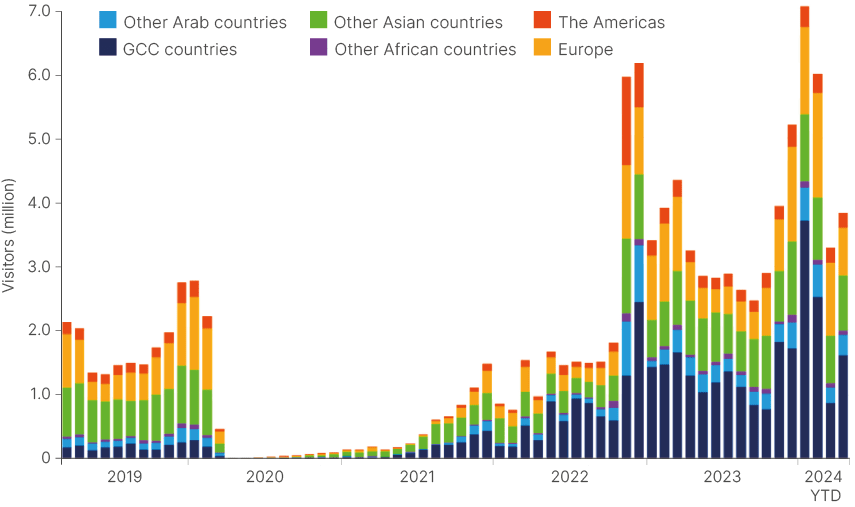

Progress has been made, including meaningful investments in infrastructure, education and healthcare, as well as measures enacted to attract foreign direct investment. Hosting the World Cup was a key mechanism to accelerate such diversification and tourism is seen as a major catalyst for socio-economic growth, by attracting investments, creating jobs and positioning the country as a global destination.

Qatar aims to increase yearly visitors to more than six million, from the four million who arrived in 2023. Hamad International Airport’s (DOH) 63% increase in passengers since its construction in 2014 – to managing 45 million passengers in 2023 – is evidence of success. This should be tempered by the airport’s role often as a transfer gateway, rather than end destination. Tourism numbers have remained high post the World Cup, and it will be important the tourist mix does not become skewed to regional tourists rather than potentially higher discretionary spending Westerners.

Fig 3: Qatar visitors

3. Are growth drivers changing?

Absolutely, but right now that is less important...

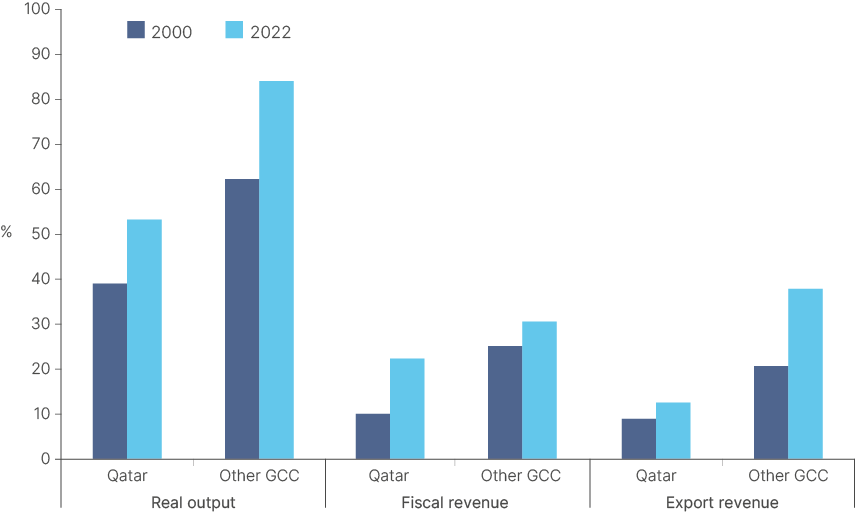

There has been evidence of economic diversification, with the non hydrocarbon share of GDP steadily rising to over 60%, yet hydrocarbon revenue still dominates, contributing to around 80% of the 2024 government budget.

However, this risks oversimplification and the reality is that Qatar’s future economic growth drivers are two sides of the same coin. The anticipated expansion of LNG is so significant that it cannot help but overshadow ambitions to diversify the economy in the immediate term. The scale of resultant GDP growth and revenue generation uplift can act as tremendous supports for financing the nation’s Vision.

LNG benefits from structural demand drivers underpinned by its role as a decarbonisation transition fuel providing recurring and stable long-dated revenues. This also stands in contrast to other Gulf states that have embarked on similar diversification journeys, yet whose financing relies on much more volatile, and less sustainable, oil revenues.

Fig 4: Non-hydrocarbon’s economic importance

4. How significant is North Field Expansion?

Potentially groundbreaking...

The North Field is set to expand over 60% in the next three years, representing an approximate 50% increase in Qatar’s gas exports and a 35% increase in total hydrocarbon exports.

Initially, the project undertaken by QatarEnergy is set to see four additional ‘mega trains’ expand capacity to 110 million metric tons per year (mtpa) by 2025, with a further two trains reaching a total of 126mtpa by 2027. Announcements since suggest more upside than downside risk to current estimates following further discoveries.

It is noteworthy that the LNG contracts negotiated as part of the expansion are over much longer periods than historically. For example, QatarEnergy signed a 27-year deal with Sinopec for the supply of four million tonnes, as well as a 15-year deal with Bangladesh for one million tonnes. The longevity of these deals supports Qatar’s fiscal position given it will create a long-term, low-volatility source of revenue.

LNG is also likely to become the global transition fuel to meet decarbonisation targets, lending increased visibility to demand growth. Natural gas emits 50% less CO2 than coal, its overall environmental footprint is also much reduced (no dust). Gas is versatile (being used for heating, electricity generation, production of fertilisers and other industrial products) and transportable. It is also available on demand, which can fill renewable energy supply gaps. The energy is not without its challenges though, with costly and specialist infrastructure necessary.

To put North Field Expansion in perspective, the Economist Intelligence Unit estimates real GDP growth for calendar year (CY) 2026 could increase to approximately 6% and then 14% in 2027. Should potential production increases be mapped onto the current full-year (FY) 2024 budget, all else equal, this would lead to an increase in oil and gas revenue of over QAR 82bn (USD 22bn) to an overall QAR 242bn (USD 66bn) by 2030. As such, the fiscal impact of these developments will have a material impact on the rest of the economy, assuming it is effectively drawn upon. Disruption to shipping routes requires monitoring, although Houthi rebels are not expected to target Qatari vessels.

Fig 5: North Field expansion

5. How meaningful is socio-economic reform?

So far so good, but there is more to be done...

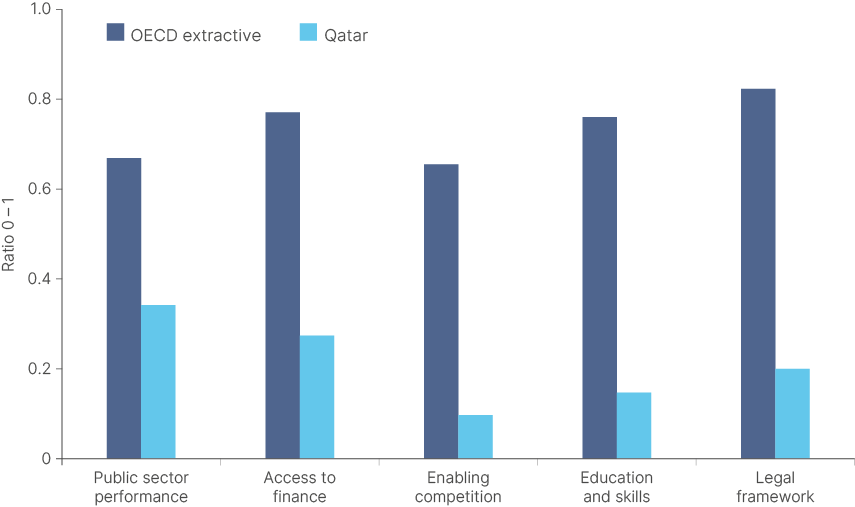

Qatar has already delivered significant reform to its labour market. For example, it was the first GCC country to abolish the Kafala system, which had historically tied workers to their employers, and hence created difficulty changing jobs. Probation periods for employees have been reduced and measures implemented to protect workers and improve their working environment. Residency programmes and work visa assistance have been put in place to attract more high-skilled workers, and there are policies to encourage greater female labour participation (although Qatar is second only to the United Arab Emirates in the Middle East with 53% women participation).1

Total public expenditure on education per student is significantly above that in other GCC countries and an ‘Education City’ has attracted a range of renowned foreign universities. Healthcare services and related infrastructure have also been improved.

Incentives have been put in place to attract foreign investment, for example, by allowing up to 100% foreign ownership of businesses in most sectors. Regulation has also promoted public-private partnerships, although more could be done to reduce the strategic advantages of state-backed firms. Bankruptcy regimes have strengthened the financial architecture to facilitate access to capital and support mechanisms are in place for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). However, the dominance of state-backed or government enterprises, often operating under favourable licences, risks ‘crowding-out’ private enterprises, in particular SMEs.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) highlights several areas of development for a country where more than 90% of Qatari nationals are employed by the public sector.

Fig 6: Structural Performance

6. How investable is the Qatari stock opportunity?

Significant and it is set only to be enhanced...

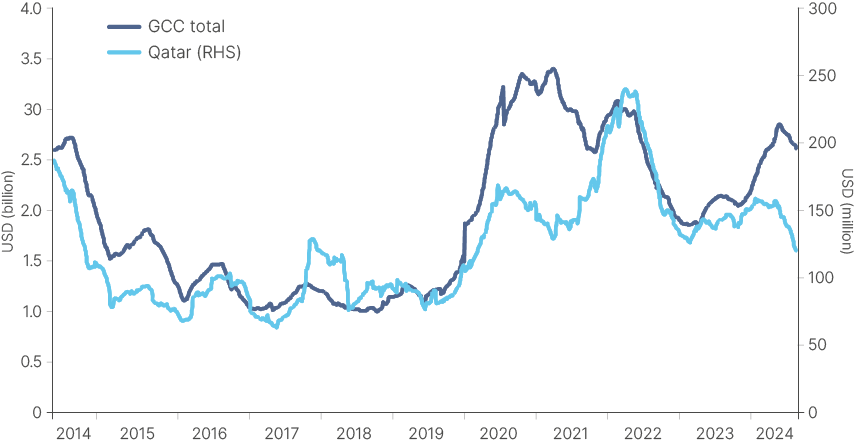

Currently, the stock exchange has a total market capitalisation of USD 163bn comprising 52 companies, a little over half of which with average daily trading liquidity above USD 1m. The domestic stock exchange average daily traded value is around USD 150m.

Qatar already offers investors a liquid and attractive range of company investments across large, mid and small market capitalisations. Examples include fertiliser and transport companies that leverage the abundance of natural resources, enjoying production cost advantages and future growth from North Field Expansion; and high quality banks, some with de facto government support and ‘safe haven’ characteristics, while others deliver strong returns from growth in Islamic finance. There are healthcare insurance and hospital companies waiting to benefit from mandatory health insurance, and leading IT services and telecom companies, often with monopolistic positions and strong pricing power.

Fig 7: Qatar ADTV USDm

7. What is the future for capital market development?

Bright and potentially transformational...

The Qatari authorities have rightfully highlighted capital market development as a key strategic initiative. It plays an integral role in the National Vision. The CEO of the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) summarises the potential best: “Qatar is uniquely positioned”.

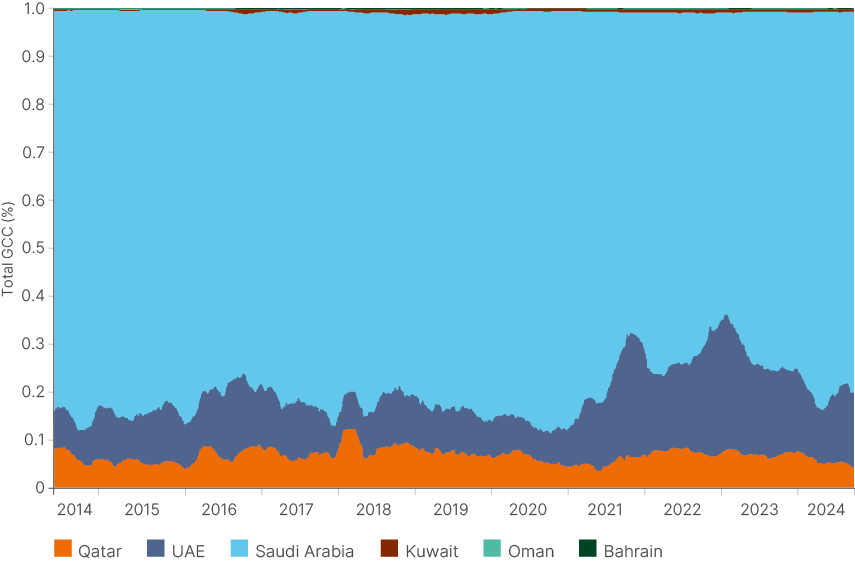

The prospect for greater market breadth, depth and liberalisation can transform Qatar as an investment destination for global investors. Several steps have been identified, and some measures enacted, yet progress needs to continue, especially given high intra-regional competition for capital.

Fig 8: Average Daily Traded Value US Dollar – Regional Market Share

Qatar is taking steps to increase the market free float, to improve price discovery and to improve access for foreign investors. For example, a domestic market-making programme has been established and several companies plan to reduce or remove foreign ownership limits. Developing the local asset management industry will also help to diversify the asset base (which is currently 85% dominated by local individuals) and the authorities have already started working with global asset manager partners (including Ashmore) to accelerate market depth and liquidity.

Reform implementation will also need to be at the company level, and here there is low hanging fruit. To improve investability, company management should ensure global standards are embraced and minority shareholders protected for example around accessibility to senior management and the generation of periodic reporting (in English), including for both financial and non-financial data.

The stock exchange is working to attract more listings, and to introduce more exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and derivatives to enhance market complexity. The potential for greater stock market liberalisation is arguably where Qatar is indeed ‘unique’. Qatar was among the first Gulf countries to list the downstream subsidiaries of national assets, such as those associated with the national energy and petroleum companies. This model has since been copied by several other Gulf states. However, there is meaningful scope to encourage the issuance of companies benefiting from policy diversification away from hydrocarbons. Whether the authorities take the decision to transform the investment landscape by directly listing primary gas operator QatarEnergy remains to be seen. The precedent has already been set elsewhere following Saudi Aramco’s (Saudi Arabia) and ADNOC’s (Abu Dhabi) listings in 2019 and 2023, respectively.

Conclusion

Qatar shares several of the characteristics of ‘smaller’ emerging markets that are often overlooked by global investors and underrepresented in third-party indices. It also has several idiosyncratic advantages over its peers, including an ambitious diversification vision financed by a ‘high quality’ funding source which is set to expand rapidly.

The greater the capital market development, the greater the flywheel of investability and global investor interest. This has strongly positive implications for equity multiples and investment flows. The relevance of third-party indices and passive tracker flows can also trigger a positive ‘liquidity shock’. In 2014, when Qatar was classified in the MSCI EM, the market appreciated around 80% in short order.

Overall, it would seem myopic to consider Qatar through only a cyclical lens when its structural advantages are only just beginning to shine through.

1. Source: Gulf Research Centre 2023.