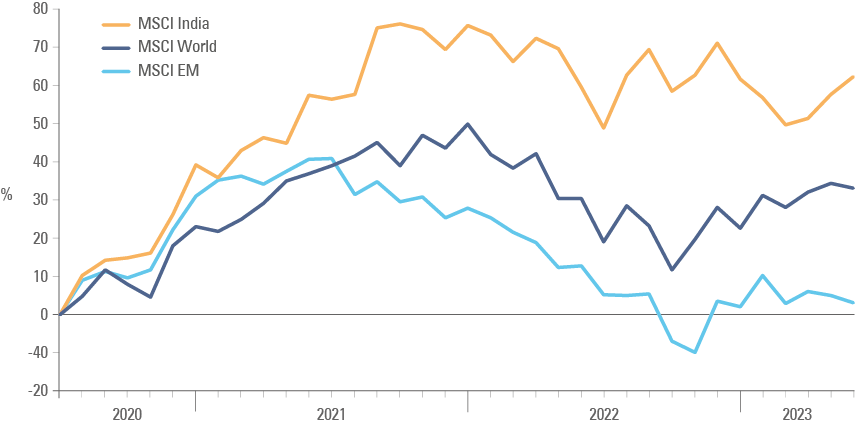

India has a compelling investment case. Over the last ten years, the MSCI India index has delivered over 135% returns in USD. Over the last three to five years, the same index has delivered 69% and 56% returns respectively, outperforming the MSCI Emerging Markets (EM) over all periods and outperforming Developed Markets (DM) countries over the last 3-years.1

Encouragingly, the outperformance is explained by structural drivers. The structural reforms implemented by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration, alongside India’s favourable demographic profile and the intention to diversify global supply chains away from China, is leading to higher investment in manufacturing, which translates into superior gross domestic product (GDP) growth potential.

Investment in manufacturing has historically been associated with larger multiplier effects on the economy via productivity gains than in the service sector. The more complex the products and processes, the greater the multiplier effects. Large technology companies recently announced India will be a key hub for manufacturing.

Furthermore, India’s demographic profile looks set to improve further by 2030. The country’s young and productive labour force anchors India’s large potential GDP growth, and stands in sharp contrast with the strained labour supplies due to ageing populations notable in several DMs.

Moreover, as India’s economy expands, it will likely become an increasingly important player on the geopolitical space. Despite its past differences and clashes, Modi has effectively allowed the country to get closer to the United States (US), taking a neutral stance to the Ukrainian war (albeit criticising Russia) and avoiding conflict with China.

Structural drivers to GDP growth: Economic reforms and demographics

What makes the Indian investment story so compelling is the fact that most factors underpinning its strong economic performance are structural in nature. The Indian government has implemented several game-changing reforms over the last ten years, which have transformed India’s economy.

- On the monetary policy front, in 2016 the government amended the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act to establish a Monetary Policy Committee with the objective of maintaining price stability. The RBI adopted an inflation targeting regime framework, helping it to anchor inflation within its 4.0% target +/-2% tolerance band.2

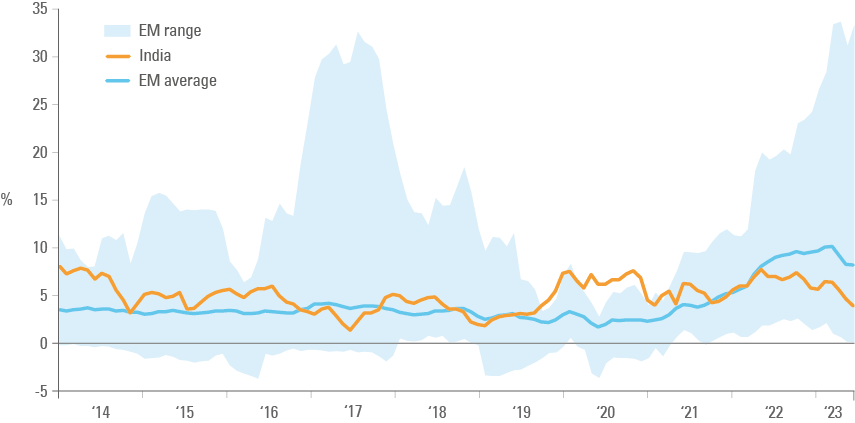

The reform resulted in a much less volatile profile for inflation in India with the difference between the Indian consumer price index (CPI) to the mean inflation across large EM countries declining from 3.1% from 2014 to 2016 to 1.1% from 2017 onwards. Figure 1 shows inflation in India has peaked at much lower levels than several other EM countries over the last 12 months.

Monetary policy stability, reflected by high real interest rates, incentivised India’s population to hold a larger share of their savings in financial instruments such as bank deposits, bonds and equities.

Fig 1: CPI inflation (yoy): India vs. large EM countries (ex-Argentina, Türkiye)

- On the fiscal front, the government’s commitment to lowering the fiscal deficit on a yearly basis led to a better allocation of government resources and lower risk of a debt crisis, buoying investors’ confidence in the economy. The government’s public spending has also become more efficient, with less expenditure in subsidies and increased investments in important infrastructure helping to foster sustainable growth. Government capital expenditure (capex) increased to the highest levels since 2007 at 2.7% of GDP from an average of 1.7% of GDP in the five years before the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Key to the efficiency gains has been the digitalisation of India’s database, achieved via enrolling 99% of its population in the 'Aadhaar card' data system. This is a biometric identification card programme which allows immediate know-your-customer identification for online bank accounts and instant digital payments. The technology was embraced by India’s vibrant financial technology sector. Also, social security spending was streamlined through the implementation of direct bank transfer schemes to the poor, which reduced the costs of subsidies significantly. The government reported 74 billion digital transactions (equivalent to USD 1.6trn) were processed in 2022, making it one of the most successful digital payment programs, alongside Brazil’s Pix digital payments system.

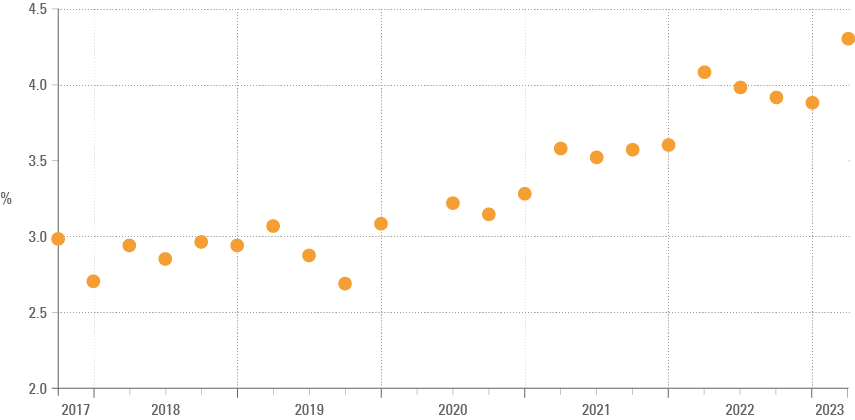

- More efficient budgeting has been aided by a key tax reform, the Goods and Services Tax (GST) Act which had a significant impact in moving the informal sector into the formal tax paying sector and led to a significant increase in tax revenues, as per Figure 2. The bankruptcy code, lower corporate taxes and labour reforms have also enhanced the ease of doing business in India. All these reforms have made India fiscally stronger than ever before, leading to a surge in investor confidence.

- India's digital ecosystem is expected to have a significant impact on potential GDP growth by boosting productivity and creating new opportunities for businesses.

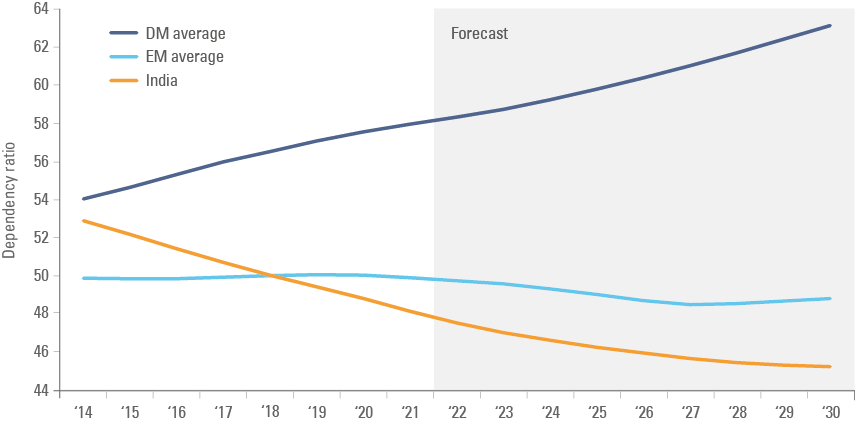

Fig 2: Goods and Services Tax as % of GDP

- Another key structural factor at play is demographics. By 2040, India is expected to account for nearly one of every five individuals in the world’s working age population. A youthful, productive workforce will be the powerhouse of India’s economy for decades to come. Illustrated in Figure 3, India's age dependency ratio (working age population divided by population below 15 and above 65-years-old) has already declined below the EM average and will continue to improve until 2030, in sharp contrast with EM stability and the sharp deterioration in DM. Furthermore, most of India’s population still lives in the countryside with the urban population at 36% of the total today. By 2045, if not before, India's urban population is likely to take the majority over its rural population. Urbanisation is associated with higher productivity, providing a sustainable base for future growth.

Fig 3: Age dependency ratio: India vs. EM, and DM (population weighted)

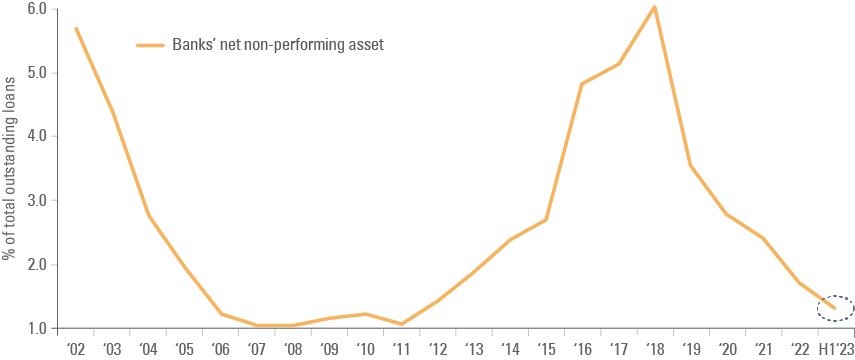

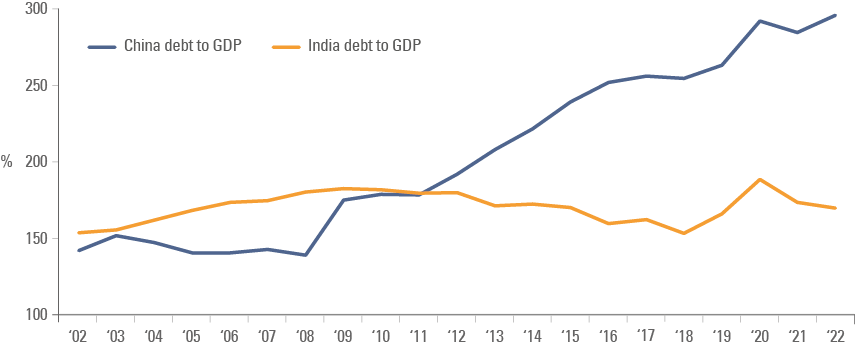

- Structural reforms supporting formalisation of the Indian economy and the digitalisation of the banking sector have contributed to significant digital inclusion and allowed for a stark improvement in bank credit growth, as shown on Figure 4. Credit expansion supported the economic recovery from the Covid shock in what we believe is a more sustainable and organic manner than the ‘helicopter money’ policies undertaken in the West. Furthermore, non-performing loans improved to the lowest levels in 20 years, as per Figure 5. The fact that credit growth did not exceed nominal GDP meaningfully suggests the current expansion is sustainable, in our view, as India’s total debt-to-GDP (government, corporate and household) has remained stable over the last 10 years, much in contrast with the developed world and China, where total-debt-to GDP increased significantly (shown in Figure 6).

Another factor suggesting credit growth is sustainable is corporate leverage. Indian companies have the best credit metrics on record, with the net debt to EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation) ratio at only 0.6x in March 2023, down from 1.8x in March 2013.

Fig 4: Bank credit growth (% yoy)

Fig 5: Non-performing loans

Fig 6: Total debt to GDP: India vs. DM, EM, and China

Cyclical performance

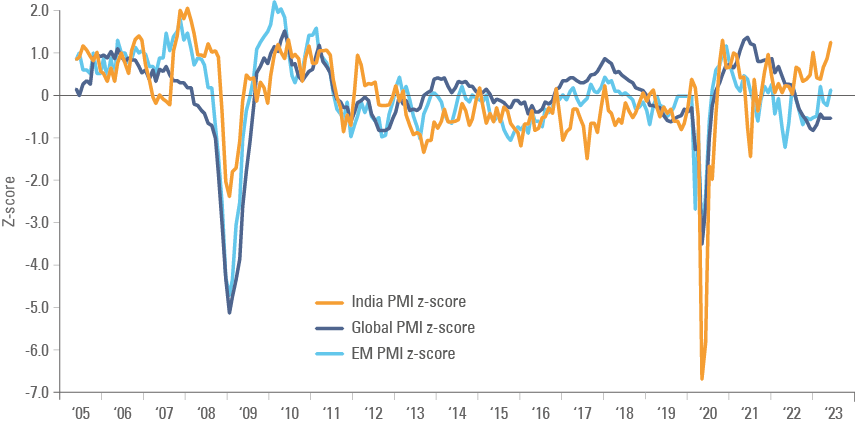

While global manufacturing has been enduring a cyclical slowdown since mid-2021, India’s economy remains robust, as illustrated by the Z-score (number of standard deviations above or below its mean) of the manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) survey on Figure 7. India’s manufacturing PMI is close to 1.5 standard deviations above its mean, whereas the EM PMI is slightly above its mean and Global PMI is 1 standard deviation below its mean.

Fig. 7: Global manufacturing PMI vs. India: Z-score

The outperformance is anchored by strong underlying demand by the local economy, as well as India’s unique position to take manufacturing business from China. Although policies designed to attract manufacturing did not lead to an improvement on India’s trade balance, as assembling manufacturing products have low value-add retention, they seem to have contributed to employment and investment.

India’s annualised exports rose to USD 450bn by March 2023 (c. 13.3% of GDP), compared to an average of USD 354bn over the last five years (c. 12.1% of GDP), while imports surged to USD 714bn in March 2023 (c. 21.1% of GDP) against the last five-year average of USD 530bn (c. 18.1% of GDP). Overall, India’s economic openness improved as total trade (imports + exports) increased to 34.4% of GDP from 30.3% on average over the last five years.

Despite the poor environment for global manufacturing, India’s business confidence index jumped to 149.7 in March 2023 compared with the last five-year average of 109.6. India’s unemployment rate has remained stable at around 8.0%, but the labour force participation rate increased to 48.5% in March 2023, compared with 47.2% on average over the last five years. Furthermore, lower commodity prices have also been beneficial for India, given its net commodity importing position.

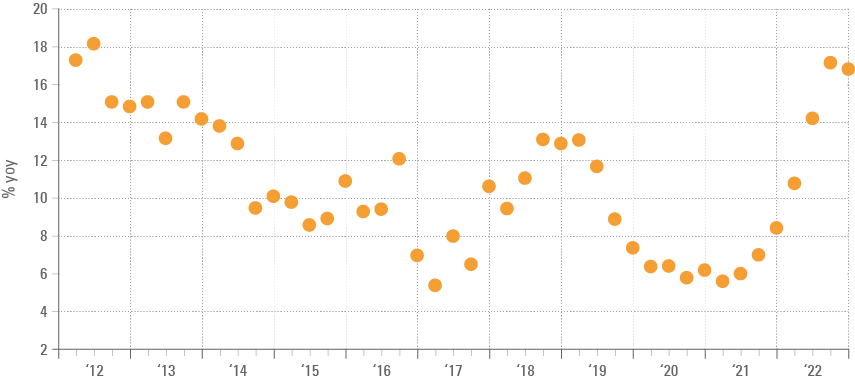

The rural sector will be another element supporting the economy, in our view. Wage growth in rural areas suffered a significant blow during the pandemic, but has more recently recovered to the highest levels since 2017, as per Figure 8. The crop volume has been strong over the last couple years, keeping food inflation subdued. More recently, terms of trade for the agricultural economy seems to be bottoming as well. There are several investment opportunities related to the rural sector which seem to be undervalued, in our view.

Fig 8: Rural wage growth

The case for a single-country allocation

Indian GDP performance has translated into strong equity market returns. The Indian stock market has risen 69% over the last three years, a massive outperformance against MSCI EM and twice the returns of the MSCI World (DM) as illustrated on Fig. 9:

Fig 9: MSCI India vs. MSCI EM and MSCI World Total Returns

Despite strong foreign investor interest, most asset allocators see India within an EM-wide focus. However, in our view, there is indeed space for single-country mandates within portfolios. The performance of Indian stocks has afforded it a growing share of the MSCI EM, but India’s potential GDP growth could warrant a structural overweight in EM portfolios, justifying a single country allocation.

India currently trades at a premium to the rest of EM. Although valuations are likely to remain elevated – a feature of a growth market – a few factors may lead to lower asset prices and allow for good entry points. For example, the reopening of China’s economy may lead to valuations of Chinese stocks increasing and may force managers to cut their underweight to China vs. an overweight to India. The general election coming in the next 12 months may have lasting consequences. Any threat to the Indian People's Party winning re-election would create market volatility, albeit it’s hard to see the incumbent party losing the elections.

Ashmore India’s Intrinsic Value Framework focuses on what we feel are good quality stocks that are undervalued relating to their quality and potential. Bouts of EM equity market volatility presents opportunities to add exposure to excellent companies at undervalued levels. Conversely, the strategy aims to reduce exposure or exit positions in periods of excessive exuberance – when valuations are unlikely to be justified by future cash flows. Furthermore, in a market as diverse as India, additional alpha can be generated by investing in the mid-cap and small-cap space which provides more opportunities than larger cap stocks.

Energy transition

India is a sustainability story to watch. The Indian government has been actively looking to expand its renewable energy capacity. A target is now in place to have 500 gigawatts (GW) of installed renewable energy by 2030, which includes the installation of 280GW of solar power and 140GW of wind power. The renewables industry has been aggressively ramping up capacity as a result, growing at an annual rate of 17.5% between 2014 and 2019, and increasing the share of renewables in India's total energy mix from 5.0% in March 2006 to 23.9% in September 2020.

India has exciting prospects in the electric vehicle (EV) and green hydrogen space, which is also expected to contribute positively to its energy transition. The recent discovery of a 5.9 million metric tonne lithium reserve in Salal (Kashmir region), means India now owns the fifth-largest reservoir of the metal, lowering its dependency on lithium imports from China. The lithium reserves could also be a catalyst to accelerate EV manufacturing in India: Tesla and Hyundai already announced meaningful investments. Furthermore, the green hydrogen incentive programme – which aims to produce 5 million tonnes of green hydrogen by 2030 while cutting carbon emissions tenfold – is also promising. The Indian government estimates that its energy transition is projected to create 3.2 million jobs by 2050. This stands out as a clear signal that India’s steps towards a sustainable future is also potentially a winning strategy in terms of economic growth.

Geopolitics

The next G-20 summit will be held in New Delhi this September. The location couldn’t be more appropriate as India has taken centre stage in geopolitical matters. The way Modi has been courted by the West is quite extraordinary. In March, when Modi visited Australia, its Prime Minister Anthony Albanese climbed on a stage in a full Olympic Park in Sydney and joked that his guest was more popular than the previous stage occupant: Bruce Springsteen. A few weeks earlier, Albanese was received by Modi at the inauguration of the ‘Narendra Modi Cricket Stadium’ in Ahmedabad, which has a 132k capacity.

Last week, Modi was received by US President Joe Biden, who hosted a state dinner in Washington, only the fifth such occasion since the Trump presidency. Beyond the grandeur of the occasion, the state visit brought several high key announcements on security and economic relations, including numerous investment announcements on strategic sectors such as defence, technology (including super quantum computers), and renewable energy, among others. Importantly, the US agreed to sell F-35 fighter jets to India, trying to lower the amount of weapons India purchases from Russia (India has been Russia’s largest client on weapon purchases) and bring India to amore meaningful role in the Quad security group (comprising the US, India, Japan and Australia).

At the same time, India has maintained its relationship with China, Russia and other EM countries in the BRIC and G-20 forums, defending its own strategic, but first and foremost, commercial interests. It is hard to believe Modi’s charm and ability to keep a positive and neutral relationship across the largest stakeholders in the global balance of power will last, should India’s ambitions for its own economy over the next few decades materialise. But until then, India is in a unique position of being the most populous country in the world, with favourable demographics and a potential economic launchpad, but also remaining a relatively poor country on a per capita basis, which allows it to maintain a strategically ambiguous neutral position on the global stage.

The key, in our view, will be India’s ability to remain a neutral player in future kinetic conflicts. This will require walking the tightrope of pursuing its own economic interests, helping to maintain a balance of power in Asia, counterbalancing the immense influence of China while lowering the risk of an escalation in the border dispute in the Himalayas.

Summary and Conclusion

We therefore believe that India is currently in a 'sweet spot' – benefitting from structural reforms, positive demographics, and geopolitical dynamics that make it an attractive investment location. India is a key beneficiary of friendly-shoring and China+1 policies, encouraging large multinational corporations to set up a manufacturing base. Capex manufacturing is typically more powerful in generating structural GDP growth outperformance, and India is just in the early stages of becoming a global manufacturing hub. The country’s fundamentals and significant equity outperformance potential supports an independent allocation to Indian assets.

Moreover, with environmental, social & governance (ESG) factors rightly growing in importance, with sustainable practices correlated with long-term returns, India’s sustainability efforts will no doubt reap long-term benefits. This, combined with the solid investment thesis highlighted above, paints a strong picture for Indian investment.

The author thanks the contributions from Arpit Kapoor, Olivia Shaul and Iylana James.

1. Returns to 28 June 2023, including dividends

2. See: https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=148405