Since the Rockefeller Foundation coined the term ‘impact investing’ back in 2007, investors have wrestled with how best to deploy impact capital where it is needed most: emerging markets (EM). An opportunity set has evolved which now offers bond investors a way to do this at a greater scale.

Over the past four years, the supply of green, social and sustainable bonds (collectively ‘impact bonds’), has grown from USD 75bn to over USD 500bn outstanding in EM. Money raised through these bonds, issued by both corporate and sovereign entities, is used exclusively for environmental and/or social projects.

Beyond impact bonds, there is also now over USD 100 billion in public debt outstanding from issuers whose business model directly contributes to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as many issuers with the intention to move their business model towards aligning with the SDGs, if they are provided with the necessary capital.

Recognising this expanding opportunity set, Ashmore has integrated a dedicated and experienced Impact Debt team into its Investment Committee. The team’s strategies will have the ability to mobilise significant institutional and retail capital towards the SDGs.

What is impact investing?

Investments that aim to create a positive social or environmental impact while also generating a financial return.

Three principles, developed by thought leaders such as the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), have become integral to the impact investing philosophy.

- Intention: The investor’s social or environmental goals are clearly expressed.

- Contribution: Clear idea as to how the investor’s actions will help achieve these goals.

- Measurability: Impact measurement framework in place to assess the level of expected impact and monitor progress against the goal.

These pillars form the basis for impact analysis, both in instrument selection and monitoring the performance of investments within a portfolio.

What sets impact investing apart from broader ESG investing?1

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing, despite significant growth over the past decade, remains an area of confusion for many investors, with a lack of standardisation in approach by asset managers, and a plethora of terms used to explain those approaches. The common thread among them all is the consideration of environmental, social and governance factors in some form. Most follow one of two broad approaches:

- ESG integration: Strategies that consider ESG information if such information is relevant to the strategy’s risk-return objectives. They have processes that consider ESG information with the aim of improving risk-adjusted returns.

- ESG characteristics: Strategies that have committed to take, or refrain from, specific actions related to certain ESG issues. They have policies that control exposure and contribution to specific ESG issues.

The former focusses on integrating ESG factors to improve risk-adjusted returns; the latter focusses on building portfolios with certain ESG characteristics. Both are valid, helping to deliver on the risk-return objective or helping to align portfolios with client values or beliefs. But neither has delivered any meaningful real-world change, leaving ESG investing vulnerable to criticism.

Impact investing, in contrast, has a clear dual objective: financial returns and positive, measurable non-financial outcomes. Impact strategies have an explicit statement of intent, and an action plan, to help bring about a target future state in ESG conditions, and a process to measure progress. They go beyond risk mitigation and portfolio engineering to allocate capital to investments that deliver positive real-world, measurable environmental and/or social impact.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals and defined KPIs for each provide a widely recognised framework for assessing impact, guiding investments towards solutions for a broad suite of global challenges, including poverty alleviation, affordable healthcare, and environmental protection. This common standard allows managers to report transparently on both financial returns and KPIs on impact.

Framework for creating social and environmental impact: SDGs

The adoption of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 provided a global blueprint for sustainable development, incorporating economic, social and environmental factors.

These 17 goals, underneath which are 169 measurable targets and 232 indicators, were adopted by all UN member states. Since their publication, the SDGs have become synonymous with the intentionality behind impact investing, given their global, holistic, measurable nature. Impact investments made today often aim to align with at least one of the 17 goals, and measure success against it.

As per the UN, the SDGs:

“Recognize that ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth – all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests.”

Fig 1: The 17 UN SDGs

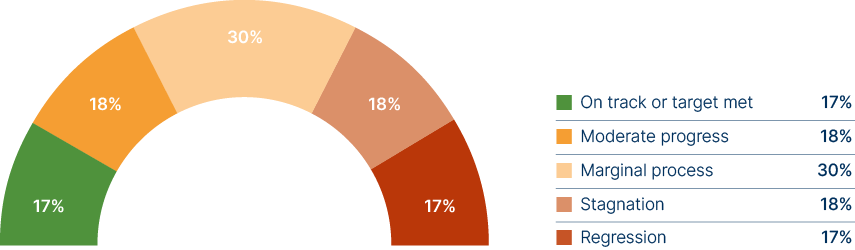

While concerted efforts have been made since 2015 to progress towards the SDGs, achievement of the goals remains elusive. Based on its most recent research, UNCTAD estimates that across all 169 targets that sit beneath the SDGs, only 17% are on track or have been met:

Fig 2: Progress towards the SDGs

With only 5 years left until the original 2030 target date for achieving the SDGs, over 80% of targets are behind schedule, and all 17 goals are behind schedule.

Why impact in EM is so essential

To address global social and environmental challenges, efforts must be focused most closely on emerging markets. According to the UN’s 2022 Multidimensional Poverty Index, which covers about one-third of the development goals, there are 1.2 billion people in 111 developing countries living in multidimensional poverty.2 This subset of countries represents 92% of the developing world’s population, where 19% of people are deemed to be multidimensionally poor. EM populations also tend to be most exposed to societal injustice, given often weaker and more volatile governance.

When it comes to the effects of climate change, such as global warming and extreme weather events, EM is again, much more vulnerable than the developed world. This is due to geography, but also to poorer infrastructure and a heavier reliance on domestic natural resources.

While carbon emissions are beginning to decrease in the developed world, they continue to increase rapidly in the global south. Over the last decade, developing countries contributed 95% of the global emissions increase, and 75% of total emissions in 2023. Given that many high-growth countries across EM are still in early stages of industrialisation, this trend will continue unless clean energy technologies are deployed to support countries’ transition to industrialised but low-carbon economies.

The principal barrier to companies achieving sustainable outcomes across EM remains limited project finance. But despite the clear case for more capital flows to EM, allocators have reduced exposure to EM since the SDGs were adopted. The latest annual financial gap to achieving the SDGs was estimated at over USD 4trn for EM, up from USD 2.5trn in 2015 (UNCTAD, 2023).

UNCTAD published a breakdown of the USD 4trn annual financing needs in 2024.

- Clean Energy: USD 2.2trn needed for renewables, energy efficiency, and transition technologies.

- Water & Sanitation: USD 500bn required for water sources, sanitation facilities, and wastewater management, linked to climate action and basic needs.

- Infrastructure (excluding Energy): USD 400bn gap, focused on transportation and telecommunications.

- Food & Agriculture: USD 300bn to eliminate extreme poverty and hunger, covering agricultural systems, food processing, and rural infrastructure.

- Biodiversity: USD 300bn for conservation, sustainable fishing, pollution control, forestry, and climate action.

- Health & Education: USD 100-600bn gap, mainly operational costs for hospitals and schools, with less emphasis on capital investments compared to other sectors.

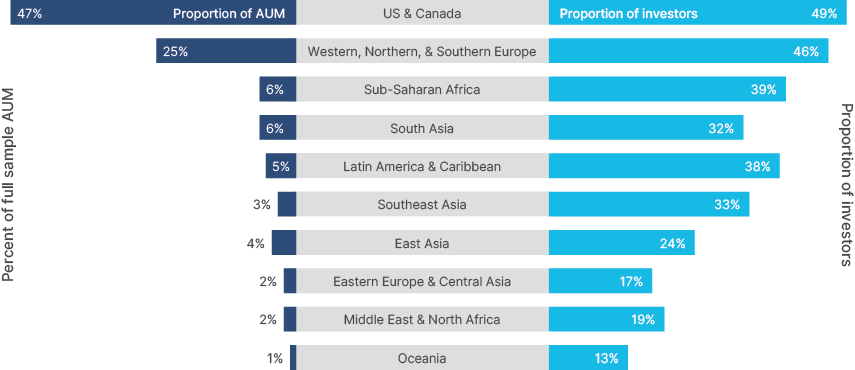

‘Achieving’ the SDGs by 2030 is a very ambitious proposition and so requires an equally ambitious commitment of capital. Anchoring aims high is important when attempting to address long-term development goals, the achievement of which would be transformational. Yet perceived risks, limited impact opportunities, and lack of scalable solutions continue to limit capital flows to EM. Within the impact investment market, only 25% of assets are allocated to EM (GIIN), a dramatic misallocation when considering where impact is most needed.

Fig 3: Asset allocations by geography of investments

Why public markets?

Financing the SDGs can only be achieved with a blend of sovereign and private sector capital. Since 2015, developed market governments’ fiscal space to fund foreign sustainability efforts has been more limited than hoped, due largely to Covid-related spending requirements, and then further pressure due to elevated inflation since.

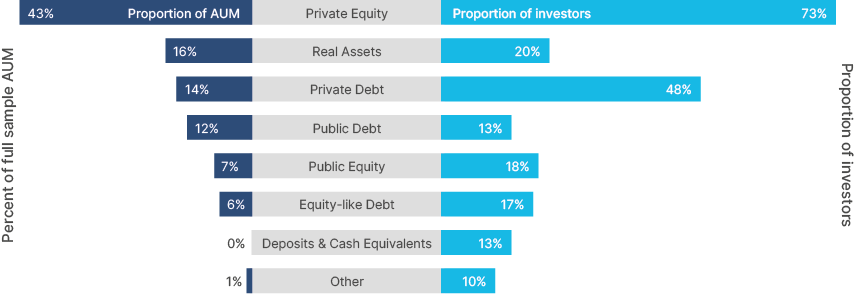

Within the private space, there have been some areas of growth. The GIIN estimates that 3,907 organisations currently manage USD 1.6trn in impact assets worldwide. This has grown 21% annually since 2019. However, the bulk of this market today is still made up of privately invested assets. In 2024, private equity remained by far the most prominent expression of impact investing, with public debt and equity combined making up just 25% of invested capital.

Fig 4: Impact asset allocation by asset class

Make no mistake, private equity and private debt investments are key to achieving the SDGs, with the ability to exert direct influence over investees, set SDG aligned KPIs, and provide capital into undersupplied areas. At times, private investors will even accept below market rate returns or receive concessionary capital from development finance providers to derisk the investments.

However, there is a need for capital to be deployed at far greater scale, in larger projects and businesses, than private markets could facilitate. The sheer magnitude of funding required to create the necessary environmental and social outcomes in the developing world, demands significant commitment of impact-oriented capital through public markets.

While public market impact strategies really remain in their nascency, they are growing quickly. Investments in public debt and public equity have grown at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 32% and 19%, respectively, over the past five years.

We outline below the key benefits of impact investing through public markets:

- Scale: public markets are multiple times the size of private markets, able to mobilise significantly more capital.3

- Transparency: issuers’ non-financial reporting is readily available, allowing investors to track and measure impact KPIs.

- Liquidity: public markets are liquid, enabling investors to dynamically allocate capital to optimize impact and financial performance.

- Return: public markets offer market rate returns, without the need for concessionary capital to derisk downside and dilute upside.

- Standardisation: public market participants can identify, advocate for, and coalesce around best practice and industry standards.

- Access: public markets are accessible by all investors, facilitating the growing appetite for impact from both institutions and retail.

- Addressable SDGs: public markets can support different impact targets to private markets, often in larger issuers and projects.

Focus on public impact debt within EM

The scale-up in public market impact investment can take place across both debt and equity instruments. However, the opportunity to achieve measurable impact alongside stable returns is particularly compelling in the debt market, given the accelerating issuance of impact bonds.

The supply of EM impact bonds, whose proceeds are used exclusively for environmental/ social projects, has grown from USD 75bn to over USD 500bn outstanding, and shows no signs of slowing down. This universe of EM impact bonds is primarily corporate (60%), but also includes sovereign (25%) and supranational issuance (15%).4 To advance the SDGs, each of these issuer types are important as they contribute towards different SDG targets, broadening the impact potential. For example, corporate issuers spending big on climate mitigation capex, sovereigns addressing public services, and supranationals advancing financial inclusion.

Impact bonds are driving impressive real-world outcomes. Take emissions avoided, a key metric for many environmental projects, and relevant for several SDG targets. Recent research has highlighted EM accounts for 99% of the top-performing green bonds globally (those avoiding over 1,000 tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions per USD million invested) as a result of funding renewables in previously fossil fuel-dominated power grids.5

Looking beyond impacts bonds, there is now over USD 100bn outstanding from issuers whose business model contributes directly to the SDGs. These range from renewable energy producers to telecoms tower operators providing digital connectivity for the first time in sub-Saharan Africa. There is also a growing stock of issuers with the intention to move their business model towards contributing to the SDGs, if provided with the necessary capital.

Combined, these three opportunities contribute to all 17 of the SDGs, via bonds from over 400 issuers in more than 40 developing countries. Higher quality disclosure, both from companies and from data providers improving their ability to measure impact outcomes, and the secular growth of companies targeting the SDGs, will continue to expand this investible universe.

Importantly, this opportunity set does not amount to concessional finance. Rather, it is part of the broader hard currency debt universe in EM, which has consistently delivered long-term outperformance versus developed market debt, with higher Sharpe ratios. For instance, EM corporate debt rolling five-year returns since December 2009 has outperformed US Investment Grade (IG) and EU IG at least 80% of the time, with volatility in line with EU IG and well below US IG.

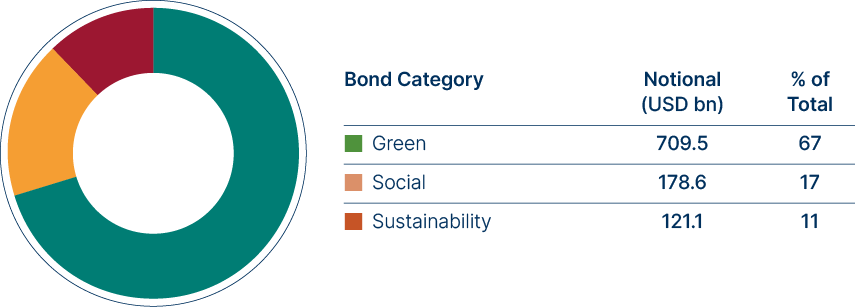

Fig 5: Green labelled bonds represent 2/3rds of the global impact debt universe

Ashmore’s impact investing process

Recognising the potential of this rapidly growing universe, Ashmore built out a new, dedicated Impact Debt team late last year, aiming to mobilise material investor capital towards the SDGs over the coming years. Ashmore will launch its EM Impact Debt fund in 2025, with the objective to generate positive, measurable environmental and/or social impact, aligned with the UN SDGs, alongside an attractive total return.

The strategy will focus on hard currency corporate bonds, with the flexibility to allocate to sovereigns and supranationals.

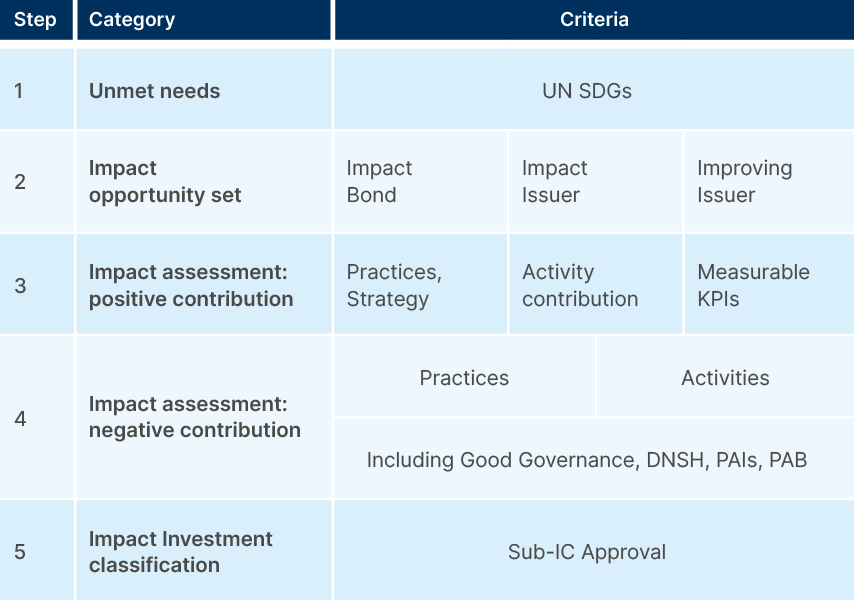

All potential investments must meet a high hurdle, as governed by Ashmore’s Impact Investment Framework, passing two tests to be classified as an Impact Investment:

1. Positive contribution test

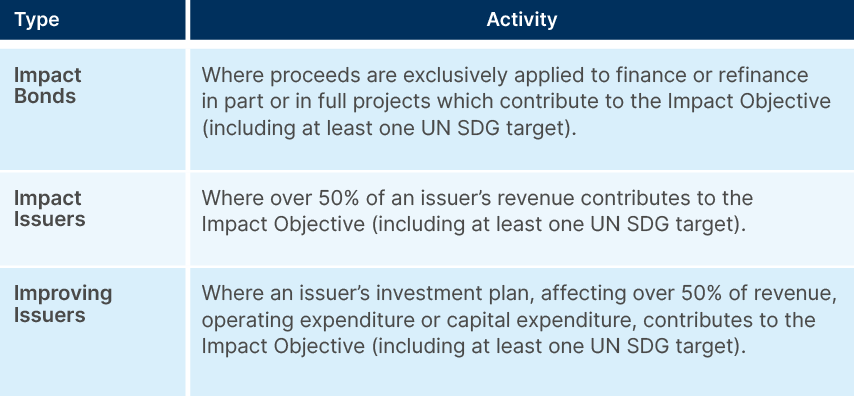

The positive contribution test assesses first whether an issuer’s practices – including strategy – broadly align with the principles of the SDGs, and second whether the specific activities being financed contribute to one or more of the 169 targets beneath the 17 SDGs. Ashmore will consider three types of structures, at the project, revenue, or investment plan level.

Fig 6: Positive contribution test

Each activity assessed as contributing to the impact objective will have one or more output or outcome KPI assigned to monitor and measure the environmental and/or social contribution of the investment over time to at least one UN SDG target.

2. Negative contribution test

No issuer is perfect. However, Ashmore does not believe in ‘netting’ positive and negative contributions, which often occur across different timeframes, affect different stakeholders, and may not be possible to measure or quantify. Investments are excluded from consideration where Ashmore determines an issuer’s activities or practices cause significant harm to the UN SDGs, using the following criteria:

- Issuers in breach of the EU Paris-Aligned Benchmark exclusion criteria.

- Issuers involved in activities or controversies causing significant harm to the UN SDGs, including considering Principle Adverse Impacts and controversy screening against the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (the ‘UNGPs’).

- Issuers that do not score a combined score of at least 4 according to Ashmore’s ESG scoring process on two out of three of the ‘E’, ‘S’ or ‘G’ combined scores.

- Issuers that Ashmore determines do not follow good governance practices, namely those that do not meet a combined score of at least 4 for governance in accordance with Ashmore’s ESG scoring process.

Impact Bonds whose proceeds help to resolve the above exclusions, and where the issuer has a clearly defined plan to address the exclusion, remain eligible for investment. This does not apply for issuers determined to be in violation of the OECD Guidelines, the UNGPs or the UN Global Compact principles.

In passing the positive and negative contribution tests, all Impact Investments contribute to an environmental and/or social objective, do not cause significant harm to any environmental or social objective, and follow good governance practices and therefore are deemed SFDR Sustainable Investments as they meet the requirements and definition outlined in SFDR Article 2, point 17.

Impact investments will only be purchased and held where they also pass fundamental and valuation assessments and thus offer both positive impact and financial return.

Ashmore’s impact investment process may be summarised as follows:

Investor contribution

The impacts associated with Ashmore’s investments are generated by issuers’ activities. Investments made or increased via primary markets directly provide issuers with the capital required to undertake those activities. Investments made or increased via secondary markets increase the portfolio’s share of the activity financed, may affect an issuer’s cost of capital and demonstrate support for the issuer’s strategy, but do not directly change the overall impact that activity generates.

There continues to be debate on investor additionality within public markets. The impact debt strategy will initially focus on the outputs and outcomes associated with the activities financed by the portfolio, without claiming they only occurred due to Ashmore’s investment. Hence, the fund managers talk in terms of financing specific activities which contribute to the SDGs. This may change as market standards regarding additionality emerge.

Impact engagement

Investor engagement is an important part of the investment process across many Ashmore funds but is particularly central to the impact investment process. Ashmore’s engagement report outlines Ashmore’s strategy of direct engagement, collaborative and collective engagement, escalation strategies, and the exercising of voting rights and responsibilities across strategies.

Within impact strategies, Ashmore aims for targeted engagements, focused on real-world outcomes around four themes:

- Enhancing positive contribution to the SDGs

- Reducing negative contribution to the SDGs

- Improving disclosure around contributions to the SDGs

- Increasing allocations to impact investments in EM

For topics 1-3, issuer engagement will often come pre-investment, to ensure it passes Ashmore’s positive and negative contribution tests, for instance helping an issuer to design a robust and transparent green bond framework, or to develop its sustainability reporting. Engagements with current holdings will be made in areas where there is an opportunity to improve impact outcomes meaningfully. Engagement may also be used as part of the escalation process.

Lastly, Ashmore seeks to encourage the wider adoption of impact investing in EM, by participating in industry events, research and publications, particularly targeting impact investors not yet allocating to EM, and EM investors not yet allocating to impact.

Impact measurement and reporting

A key tenet of Ashmore’s impact strategies is transparency. Ashmore aims to provide clients with the impact reporting they need to assess the actual, tangible impact, positive or negative, generated by individual holdings and the overall strategy.

As such, Ashmore’s impact strategies intend to measure and report the impact associated with impact investments annually, at both security level and portfolio level, based on data from the most recently available full, prior fiscal year. Ashmore aims to report data as far along the impact pathway (the sequence of events that connects inputs to short-term and long-term outcomes) as reasonably possible. In other words, not just activities, but also outputs, and outcomes too where available. Ashmore believes impact can only be truly achieved and measured over the long-term. Consequently, the typical holding period for each impact investment will be at least three years.

Conclusion

Financing the SDGs in the developing world is essential for ensuring long-term global economic stability. At the heart of this effort lies impact investing, which seeks to deliver positive social and environmental outcomes, alongside financial returns.

The impact investment market is still dominated by private market strategies. However, the expansion of public market strategies, particularly public debt, has the potential to significantly scale the investment universe by mobilising institutional and retail capital. Greater demand for impact debt will likely accelerate greater supply, creating a virtuous cycle of increased investment, deeper market development, greater company commitment and disclosure on SDG related metrics and ultimately, greater impact.

With three decades of experience in emerging markets and an office network across Asia, the Middle East, and South America, Ashmore is well-positioned to raise the profile of the public impact debt opportunity in EM and capitalise on its potential.

1. With thanks to the CFA for their work on this topic.

2. “The Multidimensional Poverty Measure (MPM) seeks to understand poverty beyond monetary deprivations (which remain the focal point of the World Bank’s monitoring of global poverty) by including access to education and basic infrastructure along with the monetary headcount ratio at the $2.15 international poverty line” – The World Bank.

3. Source: SIFMA, McKinsey

4. Source: Bloomberg, 2024.

5. Source: ClimateAligned, 2024.