In addition to bridging deep social divisions in American society, President Joe Biden faces two important policy challenges. One is to eradicate coronavirus. The other is to turn the economy – and voter sentiment – decisively in his favour in time for the mid-term election in November 2022. Otherwise the Democrats could lose their slim majority in the Senate and render the Biden Administration a lame duck less than two years after taking office.

To overcome this dual challenge, the Biden Administration is likely to expand the role of the state significantly over the coming years, particularly in the fiscal space. This marks a departure from the private sector-led growth strategy, aided by very easy monetary policies, that has prevailed since the 2008/2009 Global Financial Crisis (‘GFC’).

Three factors necessitate the shift from private to public sector-led growth:

- First, the private economy is now struggling due to real exchange rate overvaluation, low productivity growth, an excessively strong Dollar, heavy debts, and growing social problems. It will therefore not be able to provide the same lift as ten years ago.

- Second, monetary policy no longer has much to offer in terms of helping to lift growth rates.

- Third, the Biden Administration has neither sufficient time nor sufficient political capital to pursue a longer-term strategy of supply-side reform-led growth.

The rise in government spending over the next few years is likely to be the biggest since Roosevelt’s New Deal and will have profound implications for the investment environment. Debt levels will rise and productivity growth will decline. Constraints on the Fed’s ability to normalise monetary policy will intensify and the risk of financial repression will increase, particularly if inflation returns. The US real effective exchange rate will become even more overvalued due to declining productivity, yet risks to the Dollar increase at the same time. The Biden Administration may also introduce changes in taxation and anti-trust policies, which could weigh on equity markets in particular.

This report outlines these dynamics in greater detail and spells out their implications for EM and other investors.

‘L’ is for loser

There are two types of US presidents: losers and winners. Winner presidents get two terms. Loser presidents are sacked by voters after just one term. All presidents therefore want to be two-termers. It is clear that Biden will face major challenges in avoiding becoming a loser president like Trump.

For one, the assault on 6 January 2021 on the Capitol Building in Washington DC shows that Biden inherits a divided country. Almost all Democrats condemn the attack as an attack on democracy, while some Republicans justify the insurgency as a defence of democracy. Some 74 million Americans voted for former President Donald Trump, which shows that either his views are not those of a crazy fringe or there is very broad-based disillusionment with the traditional policies from the Democratic Party.

In addition, Biden faces two even more pressing challenges, which, if he fails to address them, could put him firmly on track for ‘loser’ status. One is to end the ongoing Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic. The other is to return America to strong economic growth by the mid-term election in November 2022. Failure to meet these two objectives would likely cost Democrats their single-seat majority in the Senate and render Biden a lame duck less than two years after taking office.

The risk of failure is non-trivial. Perhaps the single most enduring fact in US politics is that domestic policy change saps the political capital of presidents with frightening speed. Trump was rejected after just one term despite delivering a tax cut. Presidents George W Bush and Barack Obama both became lame ducks after passing just one major domestic reform each (a tax cut and a health care reform, respectively). Prior to that, Bill Clinton passed NAFTA and then promptly lost the Senate, while George W H Bush managed to pass a tax hike, which then cost him the presidency after just one term in office.

The good old days

Biden’s predecessors were blessed with exceptionally benign conditions that enabled the private sector, aided by cheap funding due to Fed policies, to take a clear lead in the US economic recovery from the GFC. The bail out of American banks in September 2008 and Fed action to lift out bad mortgages allowed US banks to quickly re-engage in lending, which in turn enabled the private sector to play a pivotal role in the economic recovery.

Easy monetary policy was an important hand-maiden throughout the recovery. Quantitative Easing (‘QE’) pushed down real term yields in what amounts to the greatest subsidy for asset prices in world history. Much of the money created through QE ended up being recycled in financial markets, where it pushed up the prices of stocks, leveraged loans, and high yield bonds. A massive boom unfolded that ensured that investors made far more money on Wall Street than on Main Street. Foreign investors bought Dollars to partake in the American gold rush. The US government responded to low rates by borrowing more, but fiscal policy always played second fiddle to the private sector/easy money teamwork in terms of driving growth forward in this period.

More challenging times ahead

Unlike his recent predecessors Obama and Trump, Biden inherits an economy, whose growth engines are running dangerously low on fuel. The private sector is slowly being strangled by low productivity growth, excessive valuations and unfavourable market technicals, an overvalued Dollar, debt overhangs, and growing social problems.1

Monetary policy, once such a powerful catalyst for growth, no longer has the same stimulatory impact as it once did. To make matters worse, the US economy is in dire need of deep economic reforms to bring down debt levels and the fiscal deficit, address pension and social security deficits, increase productivity, etc.

These tougher circumstances mean that Biden cannot rely on a strong exogenous private sector recovery to guarantee his political legacy. He has neither sufficient time nor sufficient political capital to pursue the deeper policy reforms that would address the real underlying causes of US stagnation. At best, he can hope to pass one big reform on this side of the mid-term election. His best option – and the most likely outcome, in our view – is that Biden unleashes an almighty fiscal splurge in the hope that government can pick up where the private sector left off.

‘Acting Big’

The Biden Administration has already announced a USD 2.0trn stimulus (about 9.5% of GDP). Based on Biden’s election programme this initial stimulus may be followed by a larger and yet to be costed ‘Build Back Better’ plan spanning support for manufacturing, infrastructure, clean energy, social care, child support, education, and measures to address racial issues.2 In addition, it seems reasonable to expect bouts of economic weakness that inevitably occur along the way to trigger additional ad hoc fiscal interventions. In total, the increase in government spending under Biden may well turn out to be among the largest since Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Such a massive ramp-up of government spending will have important economic implications of which the following five would be the most important, in our view:

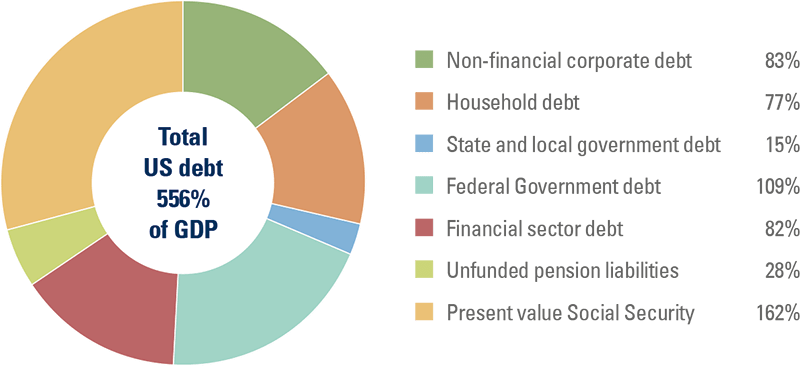

a) More debt: US debt in the hands of the public is already around 100% of GDP, but set to rise to 148% of GDP by 2029, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).3 The non-partisan US Congressional Budget office predicts US government debt in the hands of the public to reach 195% of GDP by 2050.4 These projections do not take any account of Biden’s stimulus plans, nor do they include other debts in the US economy, such as household and corporate debt as well as unfunded pension and social security obligations. When these liabilities are added the total outstanding US debt stock is close to 560% of GDP (Figure 1).

Fig 1: Total US debt by type as of Q3 2020

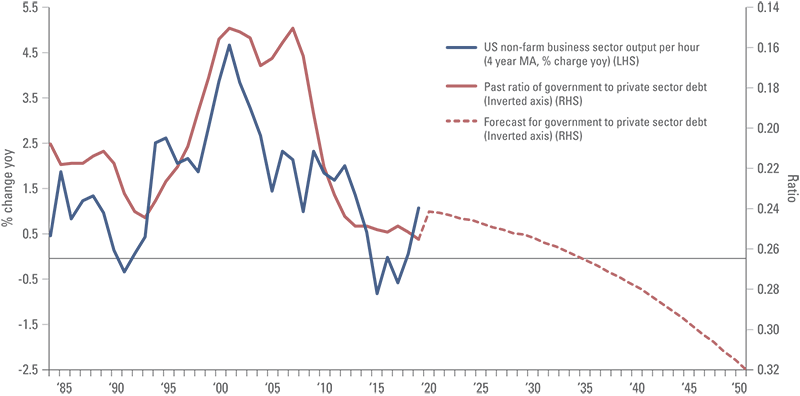

b) Lower productivity growth: Greater debt-funded government spending is likely to push down productivity growth as illustrated in Figure 2. The inverse relationship exists, because US government spending happens to be far less productive than US private sector spending. Hence, whenever the US government increases its share of total spending the average productivity of the economy declines. Traditionally, government spending adversely impacts private investment by crowding out private investment by driving up interest rates, but this mechanism has been disabled by Fed bond purchases. On the other hand, Fed purchases may well undermine private sector propensities to spend and invest by raising concerns about how

the enormous stock of government debt will eventually be repaid. The usual methods, aside from default, are through higher future taxes, more inflation, and/or currency debasement. Whatever the method, concerns only grow as the debt stock increases.

Fig 2: US productivity growth and the ratio of government to private sector debt

c) Constraints on Fed tightening: The enormous US debt burden will also weigh increasingly on the Fed’s ability to tighten monetary policy. In conditions of extremely large debt loads, rate hikes can threaten the health of the private economy and cost the Treasury a lot of money. Suppose, for arguments sake that the economy returned to 3% nominal growth and 2% inflation. A neutral Fed funds rate of 5% would then be quite reasonable, but this would imply an interest burden for the US Treasury of 5% of GDP at the current debt load plus an additional interest cost for the Fed (on USD 7trn of excess balances) of USD 350bn per year, or more than 1% of GDP (also payable by Treasury). Additionally, the Fed is constrained by the enormous financial asset bubbles it has itself created by its highly asymmetric market interventions to prevent stock prices from falling, but not preventing them from rising. Tightening monetary policy in the context of such large asset bubbles not only puts markets at risk, but also the economy.

d) Financial repression: If the Fed is unable or at least severely constrained in terms of hiking rates then inflation can potentially become a very serious problem. Suppose inflation returns. Yields will then rise sharply and immediately threaten the economy on account of the large stock of debt. Financial repression is the only way to keep term rates low (using yield curve control, a euphemism for financial repression). Faced with a tough choice between fighting inflation or protecting the economy and markets, we expect the Fed to protect the economy and markets and in the process lose inflation fighting credibility with negative consequences for the currency. The alternative approach of raising rates would risk a market crash, a fiscal crisis, and a deep economic recession, and could even cost the Fed its institutional independence.

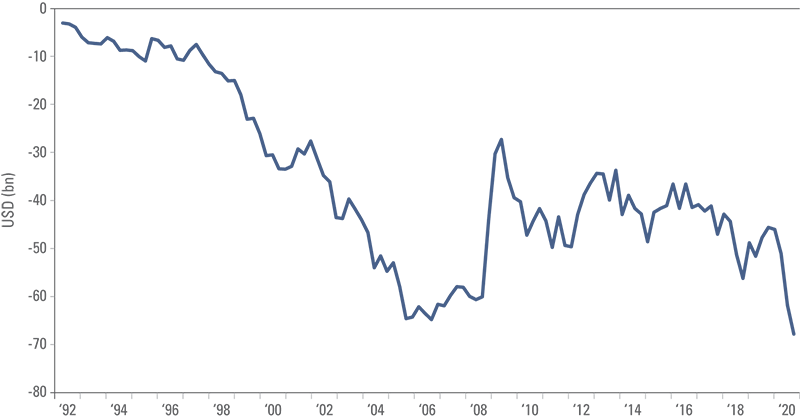

e) Further real effective exchange rate overvaluation: By most estimates, including our own, the US real effective exchange rate is already about 20% overvalued as reflected, for example, in the largest US trade deficit in decades (Figure 3). A big stimulus of aggregate demand via higher government spending may help the US emerge from the coronavirus recession, but it is not the correct recipe for the structural problems facing the economy.5 Additional demand stimulus at this time further appreciates the real effective exchange rate by undermining productivity and driving up certain costs for American businesses, thereby undermining their competitiveness. Incidentally, the risk of further trade restrictions – which tend to accompany real effective exchange rate overvaluation – is also increasing. Protectionism has the same deleterious effect on businesses via the real exchange rate. Uncompetitive industries intensify their lobbying efforts precisely when they no longer have the means to generate income in conventional ways.

Fig 3: US trade balance (USD bn)

Dollar decline

Where does the shift towards greater reliance on government spending leave the Dollar? If debt levels continue to rise and trend growth rates continue to decline; if fundamental reforms are off the table and if the US economy becomes progressively less competitive; if inflation risks are gradually rising then a lower Dollar seems to be the only remaining way to restore macroeconomic equilibrium in the United States.

Investors will determine the pace of decline of the Dollar as they constantly gauge the risk-reward of keeping money in the US versus investing it elsewhere in the world. Over the next five years, we expect yield differentials alone to produce total returns in EM fixed income that are between 4 and 9 times higher than returns in US bond markets (in Dollar terms). We anticipate that EM currencies will appreciate at least 20% versus the Dollar. The outperformance of EM equities is likely to be even better than EM fixed income as inflows provide financing to capital-starved EM economies that in turn allow domestic demand to cover and boost earnings. By contrast, US equity markets are likely to face mounting challenges as the Biden Administration introduces changes in taxation and anti-trust legislation that could weigh on the most profitable segments of the US economy, including tech.

Yet, despite the prospect of superior returns elsewhere we expect the pace of decline of the Dollar to be relatively gentle for three reasons. First, investors still view US markets as a safe haven from which they are reluctant to depart, especially in a global context beset with real and imaginary angst. Second, the decline of the Dollar will not happen in a straight line, because swings in market sentiment are likely to continue to impact currencies in the short term. Third, EM central banks will intervene to shore up the Dollar if it rises too quickly. Recent Dollar weakness has already triggered FX interventions in some EM countries, including Poland, Chile, and Israel.

The official Dollar policy of the Biden Administration is that the Dollar will remain market determined.6 This does not preclude its decline, of course. One of the great advantages of being the United States is that by merely signalling a desire to see the Dollar lower the US can effectively haircut its own debt in vaults in other central banks, effectively reducing the size of its outstanding debt in foreign currency terms. This happened in the 1970s, when the Dollar lost half of its value and it is likely to happen again.

Currency wars

‘Currency wars’ will likely break out in earnest when this happens, but foreign central banks will not be able to stem the Green Tide. The Dollar will fall because someone is actively selling USD-denominated assets and buying foreign currency denominated assets. FX interventions can, at best, buy time. If EM central banks buy Dollars they add to their FX reserves, which encourages further inflows, but it also increases the money supply, and hence ups inflationary pressures and bubble risks. On the other hand, if EM central banks issue debt securities in order to sterilise inflows they may end up pushing up local rates, which also encourages inflows, while raising the domestic cost of capital and hurting their economies.

It is imperative that EM central banks prepare for this policy dilemma, because it will play out soon enough. The ideal policy for EM central banks is to facilitate an orderly appreciation of their currencies, because capital inflows are a gift in most finance starved EM countries. Inflows can be turned into ‘a positive’ for the economy as long as they go towards investment. To ensure this happens, EM governments should prioritise reforms and put in place proper frameworks for long term infrastructure investment. This helps to drive down costs for local businesses, so they are able to cope with stronger currencies.

Conclusion

The Biden Administration is likely to expand the role of the state significantly over the next eighteen months, particularly via fiscal policy in order to improve the odds of political success in the 2022 midterm election. This effort promises to transform the US from a private sector-led economy to a public sector-led economy, which in turn will have profound implications for investors in the United States and the rest of the world alike.

Specifically, US securities – including corporate bonds, leveraged loans, and equities – that derive their principal value from activity in the private sector will likely struggle as government spending is ramped higher. This may turn out to have important implications for the Dollar, because foreign investors have ploughed more than USD 13trn, or 60% of GDP, into such US assets since the GFC. While these were successful investments during the recovery from the GFC, the money is now increasingly likely to be in the wrong place as greater returns will be available elsewhere. It will therefore leave.

1. Some 43 million Americans are on food stamps based on data from April 2020, the latest available data. See: https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap

2. See: https://joebiden.com/build-back-better/

3. See latest Article IV report here: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2020/08/07/United-States-2020-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-Statement-by-the-49650

4. See latest long-term projections here: https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#1

5. The slower growth rate of the US economy since 2008/2009 is often mistakenly attributed to inadequate demand. In reality, the US has had far too much demand. The enormous US debt stock is a reflection of years of excess demand stimulus. What the US economy needs right now is to become more competitive. This requires a stronger supply side, which can only be achieved through lower costs, a cheaper currency, and higher productivity growth. Sadly, there is very little to suggest that the Biden Administration has the patience and vision to undertake the deep and painful reforms required for a true American economic revival.

6. See: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-17/yellen-to-affirm-commitment-to-market-determined-dollar-wsj