A trip to Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok highlights nuances in local investor perspectives

A trip to Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur is always enjoyable. Both are lively, vibrant cities and both countries have been enjoying a stronger than expected economic performance, even if local investors sometimes feel less impressed. In this Market Commentary, we highlight the nuances making local investors in Malaysia pessimistic despite the recent strong economic performance, while Thai investors appear less worried about politics than we expected, for now at least.

Malaysia

It is always exciting to visit Kuala Lumpur. Its majestic and endless palm tree forests contrast with the modern skyscrapers and shopping malls that bring an immediate ‘EM-feeling’. The top-down macroeconomic data shows Malaysia has benefitted from a strong economic rebound that is starting to fade with some notable signs that its economy was overheating last year.

- Real gross domestic product (GDP) growth peaked at 14.1% yoy in Q3 2022, before declining to 5.6% in Q1 2023. This compares with average GDP growth of 3.2% over the last five years.

- Retail sales are 40% above pre-pandemic levels, but industrial production is still only at pre-pandemic levels. Local consumption outpacing production is often a sign of overheating.

- The fiscal deficit narrowed to 5.1% of GDP in Q1 2023 (it touched 3.8% of GDP in Q3 2022), down from 7.0% of GDP in Q3 2020.

- Its external accounts are strong: both exports and imports are at elevated levels, as the trade surplus remains elevated due to the strong performance of exports.

Malaysia's economic boom was anchored by large counter-cyclical measures implemented during the pandemic. The government spent 2.4% of GDP in 2021 and 1.7% of GDP in 2022 in pandemic-related stimulus (mostly tax cuts for individuals and small companies). In addition, subsidies increased from 1.5% of GDP in 2021 to 3.8% of GDP in 2022. The government has now moved to consolidate these deficits and has committed to lowering the fiscal deficit to 3.2% in 2025, from 6.3% in 2021 and 5.0% in 2023, respectively. This fiscal consolidation will take place primarily by lowering subsidies, which are projected to decline to 3.0% of GDP in 2023 and to keep declining over the next few years. The government also has plans to increase taxes via goods and services tax and a carbon tax, but this is a medium-term target and will not take place in 2023.1

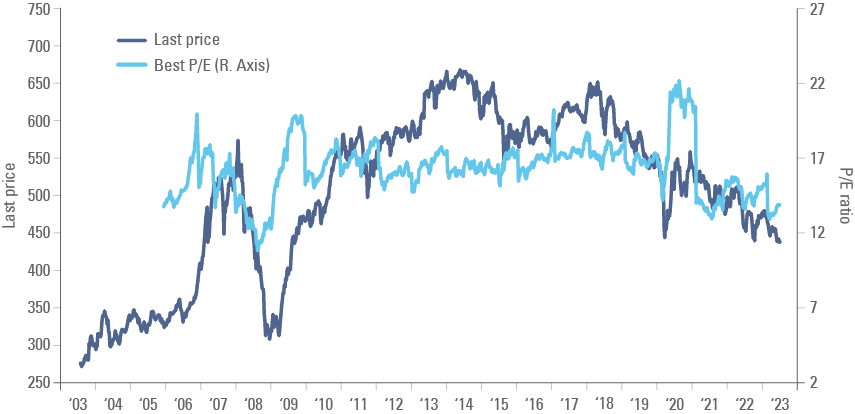

It is highly encouraging to see Malaysia’s government proactively taking tough decisions in good times. Several frontier and EM countries like Egypt, Nigeria, and Türkiye, for example, only did so when close to the brink. However, the removal of fuel subsidies and higher taxes are one element that local investors mentioned in forming their downbeat view for asset prices. Locals fear removing fuel subsidies will lead to higher costs which, alongside higher taxation, will squeeze companies’ margins. Indeed, this already seems to be priced into Malaysian stocks, which sold to the lowest level since the 2020 and 2008 shocks as per Figure 1:

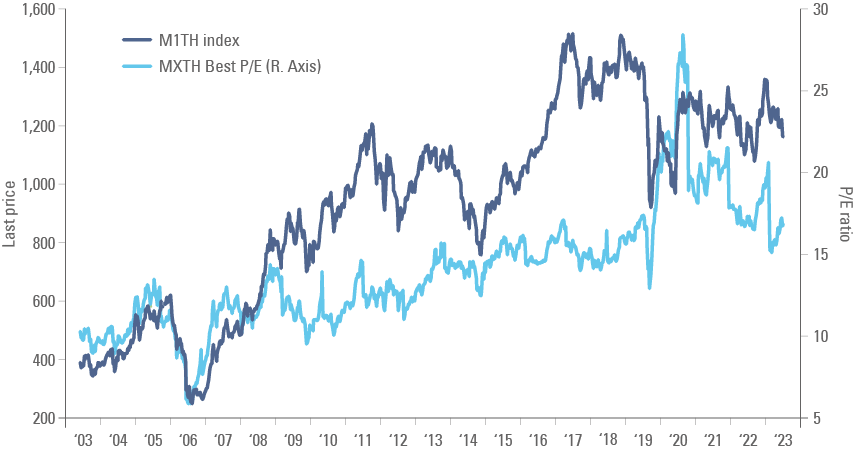

Fig. 1: MSCI Malaysia last price and price to earnings (P/E) ratio

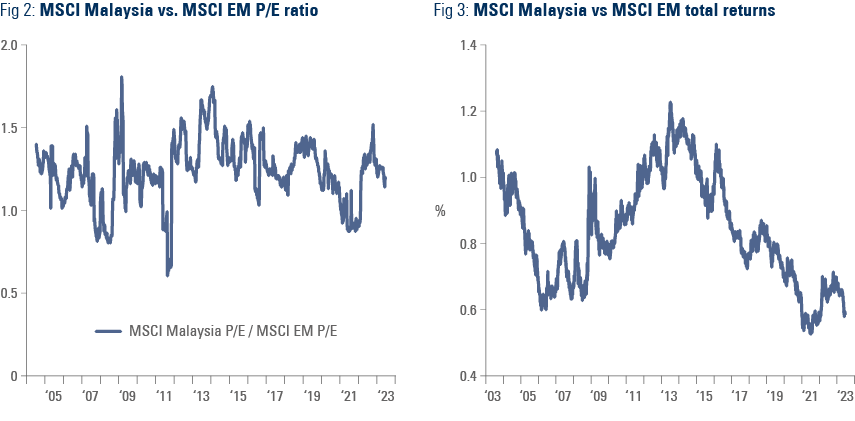

The Malaysian re-rating also seems related with the broader EM asset class. Figure 2 shows the relative P/E ratio between Malaysia and EM been trendless and sits close to its 20-year average. However, the total returns of Malaysian stocks have been underperforming EM since 2013 (as per Figure 3), which has coincided with the de-rating of commodity stocks, initially led by prices, then by environmental, social and governance (ESG) concerns and the USD rally.

Consumer price index (CPI) inflation has not risen much over the last two years (thanks to the subsidies) and has recently declined within the 2% to 3% target range of Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM). Whilst subsidy removal is likely to lead to higher fuel prices, if investors are right that companies are not able to pass the higher costs through to consumers, the BNM should keep policy rates unchanged and look-through the first effect of higher costs from subsidy removal. Indeed, after hitting double-digit levels in 2021 and 2022, producer price index inflation declined to -4.6% in May 2023.

The subsidies removal may prove painful over the short term for companies and consumers, but it will, in our opinion, have a significant and positive impact over the long run. Lower fiscal deficits will reduce debt issuance in the local market, leaving more funding available to the private sector. Furthermore, we believe cutting subsidies will have a meaningful impact on lowering Malaysia’s debt levels, allowing it more room to implement counter-cyclical policies during exogenous shocks.

Malaysia is already not quite as indebted as its Asian peers, such as Japan, where total debt (government + corporate + household debt) stands above 400% of GDP, or China, with total debt-to-GDP at around 300%. Malaysia’s debt-to-GDP stands at around 190%, which is only 40% above the median EM country, but 90% below the median DM country. Malaysia’s debt is also well distributed, with around 60% debt-to-GDP across each sector. Since 2017, Malaysia’s total debt has only increased by 7% of GDP, as corporates have de-levered aggressively. Most importantly, because of low interest rates, Malaysia’s debt service accounts for only 14% of GDP, below the average EM of 15% and Developed Market (DM) average of 18%.

Malaysia’s debt-to-GDP ratio is set to improve, in our view, as temporary higher inflation drives nominal GDP growth higher while lowering fiscal deficits. If BNM does indeed look-through the short-term inflationary spike, low interest rates will contribute to lower the debt service costs. That stands in sharp contrast with DM countries where debt-to-GDP is much more elevated and central banks are still trying to correct their own policy mistakes in 2021 and 2022, leading to higher debt service. In June, the Bank of England was forced to hike its policy rate by 50 basis points to 5.0% and is struggling to regain its credibility after several above-consensus inflation prints.

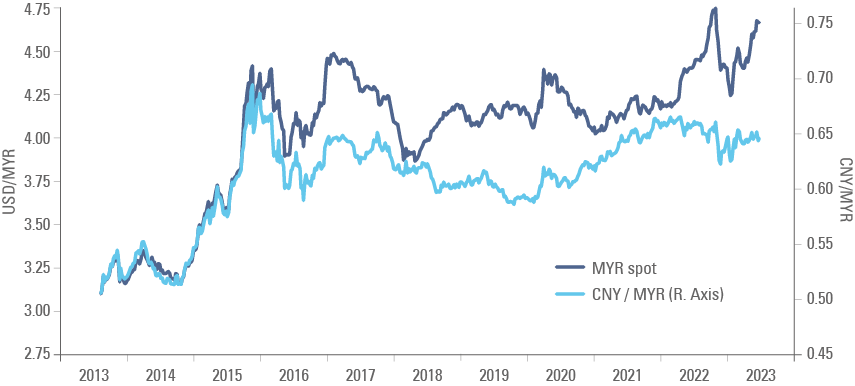

Back to Malaysia, local investors acknowledge enthusiastically that the economy is doing very well but some are “humorously disgruntled” about the poor performance of Malaysian assets. The Malaysian Ringgit (MYR) hit its lowest historical levels against the US dollar (USD) and local equities are underperforming, albeit the connection between the equity and MYR underperformed is tenuous, in our view. The MYR weakness since the end of 2021 is related to the poor renminbi (RMB) performance as highlighted in Figure 4, standing in contrast with the 2016 and 2018 sell-offs when the MYR weakened both against the RMB and the USD. Back then, the Ringgit was mired by political risks including the 1MDB scandal that led to the fall of former Prime Minister Najib Razak. Nevertheless, the BNM it could intervene in the foreign exchange market, probably a wise measure as the psychologically important USDMYR 4.50 level was breached, leading to a negative feedback loop if unchecked.

Fig. 4: Malaysian Ringgit vs. US Dollar and Chinese Renminbi

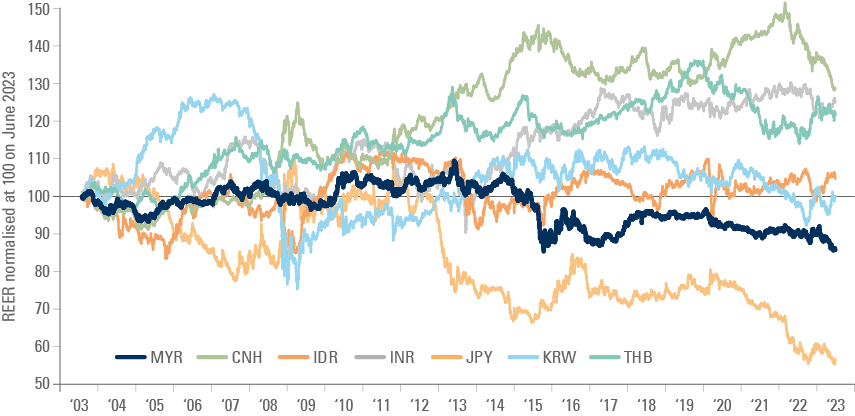

At the same time, a weak RMB has further improved Malaysia’s competitiveness. The MYR real effective exchange rate (REER) has declined the most across large EM Asian countries over the last 20-years, as shown by Figure 5. A more competitive currency for tourism and manufacturing is likely to be positive for growth over the medium term.2

Figure 5: Malaysian Ringgit REER vs. main Asian currencies

In summary we believe there is a medium-term opportunity within Malaysian assets as the periods of extreme bearishness from local investors often suggests. The poor micro-environment that locals complain about is inherently bullish for the macro, in our view. Over time, this should benefit Malaysian assets. There is also a case to be made that the potential re-rating of commodity prices (or the large cash flows from existing assets) should boost returns further.

Thailand

The mood in Bangkok felt very different than in Kuala Lumpur. Any investor looking from afar would expect locals to be extremely worried about the recent political developments. While some are slightly worried of political volatility, most investors we met appear not to be that interested in political struggles (considered a taboo topic) as the economic policies from whoever forms a government will be similar.

The coalition formed by the Move Forward Party led by Harvard-educated Pita Limjaroenrat controls 312 lawmakers in the 500-seat Lower House but has almost no representation in the unelected 250-member Senate, where lawmakers were appointed by the Royal Thai Military. To form a government, Pita needs a simple majority when combining both houses (376 seats). However, getting an additional 64-65 votes is a tall order for a young politician vowing to pass reforms intended to weaken the influence of the most important elite institutions: the monarchy and the military.

Pita received 324 votes in his favor, 182 votes against and 199 abstentions in the first vote in parliament on 13 July, 51 votes short of his target. Parliament President Wan Muhamad Noor Matha has scheduled the second and third rounds of voting for July 19.

A local investor offered a nuanced personal view: Pita would be allowed to form a government but will be ‘set up’ for failure a few quarters down the line. The investigation over his ownership of shares of a media company during the campaign is Pita's main soft spot. Last week, the Electoral Court referred the case to the Constitutional Court, increasing the political pressure on Pita. The main risk, in the short term, is the break-up of the coalition between the Move Forward Party with the Pheu Thai Party, with the latter joining the military. After voting for change, a return to the status quo would probably lead to mass protests and paralysis, an all-too familiar scenario that has played out several times over the last decades, including in 2020 when another reformist party had most seats, but failed to form a coalition, resulting in the unpopular military government re-gaining power.

Should Pita become Prime Minister and then be forced to step down in the future, Thai assets would rally but then decline precipitously, as there would most likely be protests on the streets. A third scenario – where the coalition holds, but another politician is elected as Prime Minister, with Pita holding a lesser but still important position in the government – could be the best-case scenario for markets in the medium term, lowering the risks of street protests. Moreover, a conciliatory tone could also allow for better governability and for some reforms to be approved. Things are likely to evolve quickly as at the time of writing the Speaker of the Lower House has called for the first vote for Prime Minister to take place. A myriad of other scenarios could take place as the situation remains fluid.

Whatever happens, pressure for reforms that increases the quality of Thai’s democracy will keep on building, in our view. Thailand’s King Maha Vajiralongkorn struck a conciliatory tone in a recent speech, saying Congress must hear the voice of the people. At the same time, the military had historically kept incentives for the private sector to invest in Thailand, explaining why its economy held up so well over the last few years, despite the political instability.

It is also worth remembering that whoever comes to power will implement policies to boost short-term growth. All parties promised large increases in minimum wages and cash handouts, despite the fiscal deficit standing around 3.5% of GDP in Q1 2023.

Politics aside, Thai macro fundamentals have been nothing short of stellar. The Thai Baht (THB) is the fourth strongest currency in the world over the last 20 years, only behind the Swiss Franc, Singapore dollar, and Czech Koruna, despite numerous political clashes and military takeovers over the same period. The stronger THB has not made life more expensive, as low wage inflation and a large surplus of food still render services and food prices very cheap. A Thai massage at good local parlour for THB 690 (around GBP 15) is only slightly more expensive than a lunch box in central London and let us not compare Thai restaurant and hotel prices to the rest of the world.

The economy is recovering as expected. Tourists from US, Europe (including Russia) and Asia are back. Most Chinese tourists spotted in Bangkok were sophisticated Shanghai middle class, rather than the mass tourists stopping for pictures and crowding hotels, restaurants, and temples. Hotels are busy, albeit not yet full, and despite the lack of English fluency, dealing with the locals is a true joy.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is 40% above the average of the last ten years before the pandemic, as locals cite Japanese industries investing in Thailand. Real estate is also likely to benefit from affluent Chinese individuals as the hostility of western democracies towards Chinese capital, not to mention attractive real estate prices, pleasant weather, nice beaches, and school developments catering for the foreign middle class makes. All conspiring for the THB is likely to maintains its status as one of the strongest currencies in the world, as the domestic economy and the country’s external accounts recover.

Core CPI inflation declined from 3.2% in December 2022 to 1.3% in June 2023. Nevertheless, in contrast with BNM, the Bank of Thailand (BOT) is much more worried about future inflation. The Thai government is likely to increase the minimum wage and cash handouts as the labour market is close to full employment and tourism is still recovering, which is likely to have a knock-on impact on wages. The BOT relative hawkishness, positive real interest rates and the ongoing rebound in tourism and FDI makes the THB an interesting asset to own, in our view, albeit the size and direction of the position should reflect the current political uncertainty.

Thai stocks look less undervalued, trading at 16.7x earnings against the MSCI EM at 12.2x.3 Nevertheless, the MSCI Thailand trades one standard deviation below the upward slope trendline over the last 20 years. Earnings per share have recovered 43% from the pandemic levels but are still at half the 2013 peak level. Should Thai companies regain their mojo due to higher tourism, real estate, consumption, and manufacturing, stocks can go up significantly without an increase in the P/E multiple.

Fig. 6: MSCI Thailand returns and Best P/E Ratio

Another way of accessing a country’s stock market valuation is looking at banks. EM banks currently trade at around 0.83x book value, or 0.6 standard deviations below the median since Apr 2006 (z-score), close to US banks at 0.97x (-0.6 z-score) but above Japan and Europe at 0.63x (0 z-score) and 0.65x (-0.1 z-score), respectively. In comparison, Kasikornbank trades at 0.6x book value or -1.6 standard deviations below the median over the same period, very close to the z-score lows of -1.9. Banks are typically good at capturing the cyclical picture of the economy as a bad political and economic environment leads to weaker growth and higher non-performing loans. Provided Thai politics stand out of the way, the macro picture suggests there is upside in the banking sector.

Fig. 7: Kasikornbank PCL price to book ratio

Geopolitics

The one thing in common between Thailand and Malaysia? Both countries are friendly to Western capital and want the US to be part of Southeast Asia’s balance of power. But both are also pragmatic in recognising there is no way to decouple their economies and countries from the Chinese ‘Big Brother’ next door. Heads nod in agreement across most meetings when making the case that investors should care about geopolitical risks, which are at the most elevated level since the Cuban Missile Crisis. But how can investors protect against geopolitical risks?

The first and most important rule of thumb is to invest in neutral countries. Malaysia and Thailand fit the bill. Both are likely to benefit from diversification of manufacturing away from China, receiving FDI from the West, but while still trading and hosting tourists from China (and Russia, in Thailand's case).

It was also refreshing to hear from an investor that focuses only on the real-world economy to say that they invest mostly in EM. Their assertion was that investing in both EM and DM carries the same risk, but there is much more upside in EM. We most certainly agree. The US debt ceiling showdown and large twin deficits in the largest economy in the world are evidence, in our view, that ‘risk-free’ is a concept that should be abolished from finance. The problem is that academics couldn’t figure out how to formulate an asset allocation pricing model without a risk-free proxy.

Summary and conclusion

Thailand and Malaysia, the second and sixth-largest countries in Southeast Asia, are experiencing very different economic and social realities. Thailand’s economic growth is likely to accelerate from here (should politics not get in the way), led by tourism, fiscal expansion, and investments.

Malaysia's economy is cooling down as its government unwinds the large pandemic-induced countercyclical fiscal measures.

Local investors are worried about politics in Thailand but remain confident economic growth will accelerate in most scenarios, whereas Malaysian investors are worried about that removing subsidies will eat into company profits.

The Bank of Thailand is likely to keep a hawkish stance and may even hike its policy rate further to control wages, while Malaysia's central bank is likely to look through inflationary pressures from higher fuel prices.

Valuations on equity market seem undervalued in Malaysia, and attractive in Thailand, considering its growth potential.

Structurally, both countries will benefit from neutral status amid current geopolitical conflicts, making them an important FDI destination for those investors seeking diversification away from China.

1. See: https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/CR/2023/English/1MYSEA2023001.ashx

2. See: REER is the nominal exchange rate of Malaysia against its main trading partners, after adjusted for inflation.

3. See: P/E 12-months blended forward ratio.