This document is divided in subsections related to each individual topic.

Introduction

1. Fundamentals: EM GDP growth outperforming DM

2. Where could consensus be wrong?

3. A year of two halves: monetary policy driving a recession

4. Where to hide in the short term? EM investment grade corporates

5. EM sovereign debt

6. EM debt return scenarios

7. EM local bonds: favourable technicals

8. EM equities: a year of positive inflection

9. Several EM countries are well positioned to navigate a challenging 2023

10. Fiscal policy

11. Global debt and real estate

12. Geopolitics

13. 2023 political calendar

Appendix - The Fed’s policy mistake and reasons for a 2023 recession

Introduction

Emerging Market (EM) assets were subject to three strong headwinds in 2022, namely, China’s zero Covid-19 and real estate crisis, aggressive interest rate tightening from the US Federal Reserve (Fed), and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Two out of those three factors are likely to turn from headwinds to tailwinds in 2023, while the Ukrainian war remains uncertain.

In our view, while China will almost certainly reopen its economy in 2023, the main questions are the timing and impact on the rest of the world. On the other hand, the US economy is very likely to endure a recession in 2023, forcing the Fed to pause its hikes at some time in Q1 2023 and potentially pivot to cuts in H2 2023. While the long-term picture remains challenging due to geopolitical risks and supply constraints, we believe a more constructive scenario for EM economies will allow EM assets to outperform developed market (DM) assets over the next years.

The combination of tight monetary policy leading to a recession in DM and a challenging reopening in China during the winter may keep the riskier part of the asset classes under pressure in H1 2023, a period when investment grade assets are likely to outperform. However, a true Fed pivot and the reopening of China’s economy should lead to better performance in EM equities, high yield, and local currency bonds in the second half of the year. Therefore, while investment grade bonds are likely to outperform on a volatility-adjusted basis, particularly in the first half of 2023, adding exposure to high yield towards Q2 2023 is likely to deliver stronger absolute returns over the medium-to-long term.

Section 1

Fundamentals: EM GDP growth outperforming DM

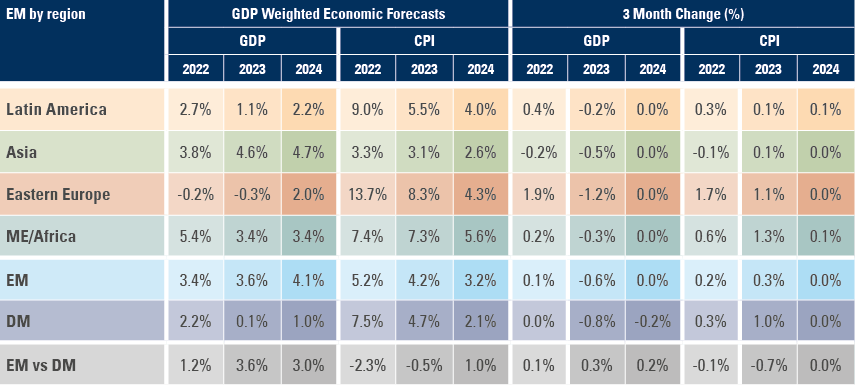

The key question for asset allocators is not how much gross domestic product (GDP) growth or inflation will be, but where the consensus for growth and inflation could be wrong. Figure 1 shows the latest average GDP growth and consumer price index (CPI) inflation expectations from bank economists. It includes 31 of the largest EM countries and the largest DM countries.1

Figure 1: GDP growth and CPI inflation expectations by sell-side economists

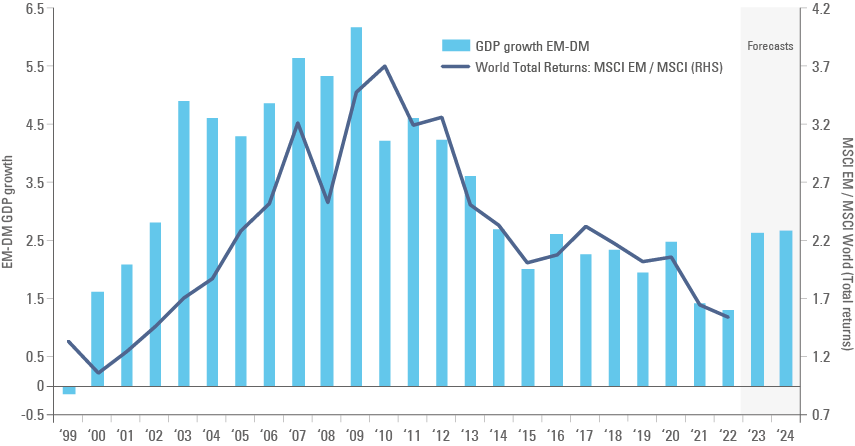

Economic growth is likely to increase in EM during 2023, driven by higher growth in China, Hong Kong, and Thailand, as well as resilient growth from the Middle East. In contrast, DM GDP is expected to decline to very close to zero. As a result, the gap between EM and DM GDP growth is likely to widen from 1.2% in 2022 to 3.6% and 3.0% in 2023 and 2024 respectively. This sets a strong backdrop for EM asset prices, even if the gap between EM and DM widens by a smaller magnitude, as forecasted by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its latest World Economic Outlook in October 2022. Figure 2 illustrates that EM stocks tends to outperform DM stocks when the EM “growth premium” increase.

Figure 2: GDP Growth EM – DM (IMF WEO) vs MSCI EM to MSCI World Total Returns

Section 2

Where could consensus be wrong?

In our view, economists may well be too pessimistic about the outlook for Latin America and Middle East growth. The main reasons behind expectations for lower growth are:

- A recession in the United States (particularly concerning for Mexico, Central America, and Colombia).

- Higher interest rates leading to slower credit growth across the region, and:

- The return of centre-to-far left leaders from Chile to Colombia and Brazil impacting sentiment.

On the other hand, Latin America is likely to benefit from the reopening of the Chinese economy, which should support commodity prices, boosting wealth effects. The sell-side was slow to incorporate the wealth effects in 2022, underestimating GDP growth in Latin America and Middle East and have revised growth significantly higher over the last three months (including in Eastern Europe), as per Figure 1. We believe there are potential upside surprises for growth coming from the region, particularly Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Peru, where the net commodity trade balance is equivalent to 9.5%-19.5% of GDP. There is also space for upside growth surprises from members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Malaysia, and Indonesia in Asia – all of which are large net commodity exporters.

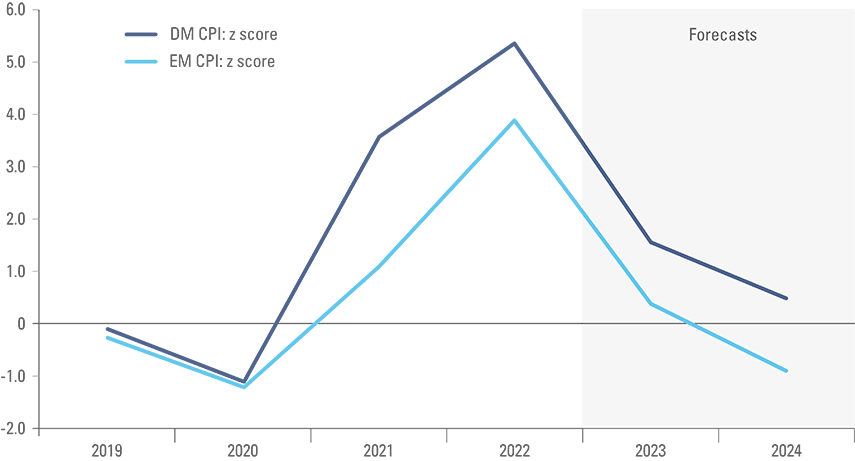

Most analysts expect DM CPI inflation to slow from 7.5% to 4.7%, while GDP growth declines to zero, a year of stagflation. DM central banks were slow to react to inflationary pressures in 2021 and the tight labour market will keep wage inflation under pressure for the remainder of Q4 2022 and likely during H1 2023 as well. However, inflation may decline faster than expected should the economic slowdown lead to a higher unemployment rate in 2023. Overall, inflation is likely to remain above average in DM but declining to below average levels across most EM countries (as depicted by the z-score in Figure 3).

Figure 3: EM vs DM inflation z-score (standard deviations above/below median since 2000)

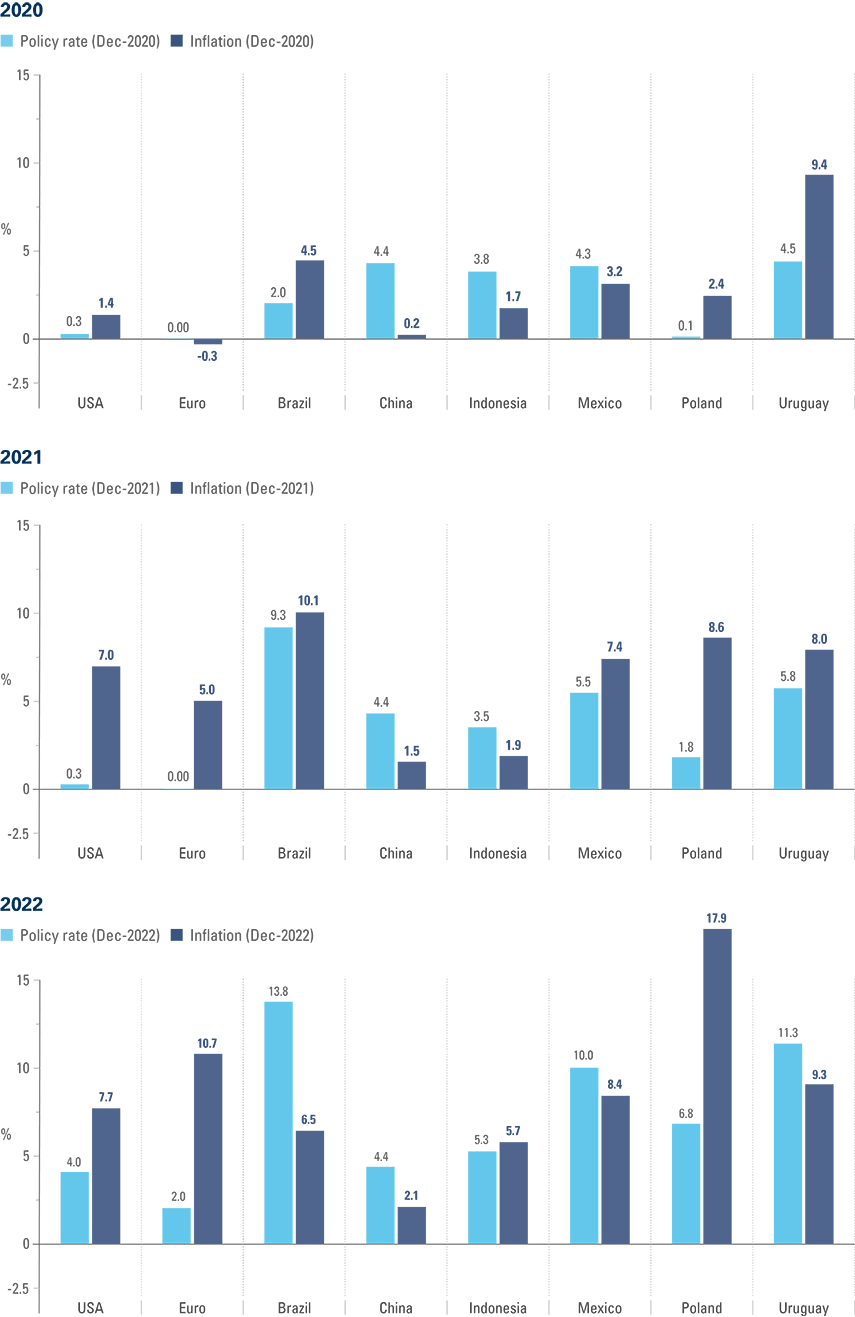

Inflation declining towards its long-term average in EM was the result of the readiness of EM central banks to react to changes in inflation and inflation expectations, with Brazil and Russia hiking policy rates as early as Q1 2021. This was also true in Eastern European and Asian countries experiencing higher inflation later in 2021 and 2022 (as per Figure 4).

Figure 4: Policy rates vs inflation large countries

Section 3

A year of two halves: monetary policy driving a recession

The Fed hiking cycle is near its final innings. The key question, in our view, is not whether the terminal rate will be at 4.75%, 5.0%, 5.25%, or even 6.0%, but for how long the Fed will keep policy rates at such elevated levels and keep tightening liquidity conditions via quantitative tightening.

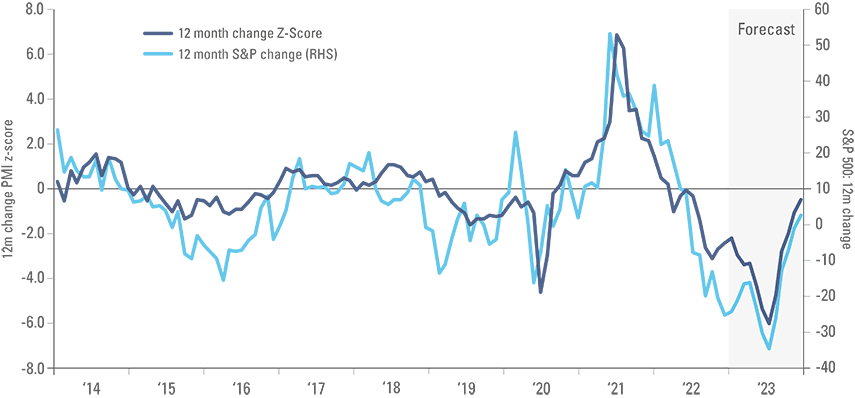

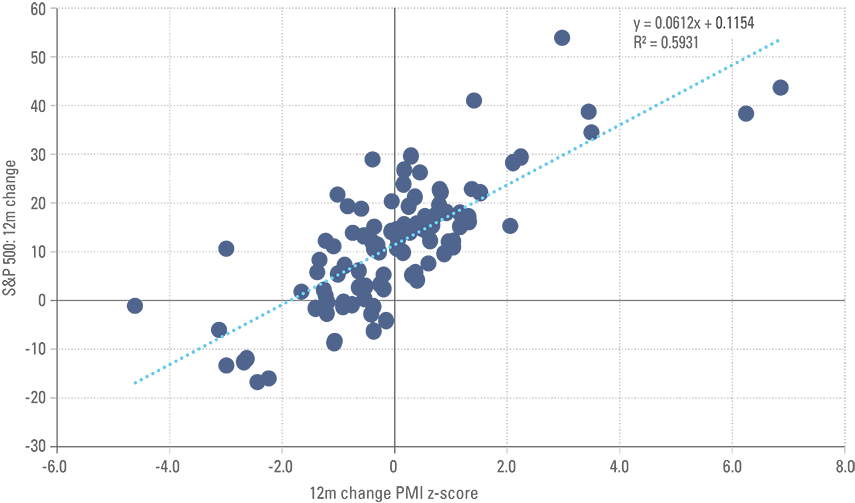

After keeping monetary policy excessively loose during 2021 and H1 2022, in our opinion the Fed moved to an overtightening mode in H2 2022. A mild recession in the US is already fully expected by economists, albeit not yet priced into US capital markets. A mild recession would be consistent with purchasing manager indices (PMIs) for the manufacturing sector falling to around high 30s or low 40s levels. This would be consistent with the S&P 500 at 3,100 to 3,400 levels, not the 4,000 it trades at today (as per Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5: 12-month rolling S&P 500 returns vs. Manufacturing PMI

Figure 6: S&P 500 vs. Manufacturing PMI regression

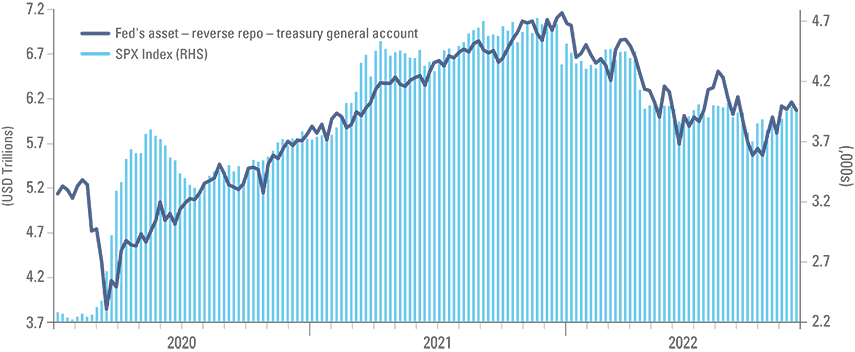

Furthermore, over the last two years, US stocks have also been remarkably correlated with liquidity measured by the Fed’s balance sheet (as per Figure 7). This is likely due to the multiplier effect of tighter liquidity conditions into the banking system anticipated by asset prices, and the fact that the market has been paying much more attention to liquidity lately. If this correlation remains in place, quantitative tightening is likely to keep US stocks under pressure.

Figure 7: S&P 500 vs. liquidity changes (Fed’s assets minus selected liabilities)2

Section 4

Where to shelter in the short term? EM investment grade corporates

In a treacherous environment of high interest rates, slowing growth and volatile equity markets, we believe high quality investment grade countries and companies will be an interesting haven for asset allocators looking for modest but positive total returns.

There are relatively fewer EM countries with an investment grade label, a result of a challenging environment for capital flows to EM over the last decade, and debatable ratings agencies biases that favour DM countries over EM (despite ample evidence of political and balance sheet risks in the former: i.e., Greece, Italy, Spain, Ireland, and Portugal in 2012; several other DMs in 2022). The EM countries left in the investment grade universe have solid balance sheets and favourable debt dynamics. Despite the solid fundamentals the yield-to-maturity on BBB sovereign debt reached 6.0% in October, the highest level since the 2008 crisis as yield on ‘A’-rated securities are now close to 5.0%.

Whilst credit spreads don’t look stretched, any recession leading to wider credit spreads would also likely push US Treasury yields lower, making the asset class an attractive destination from a total return perspective, with much lower volatility than high yield or equity markets.

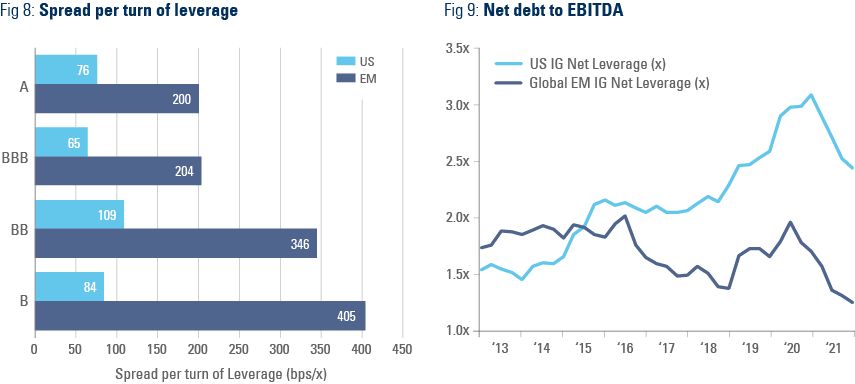

Furthermore, investment grade corporate debt offers the best balance with a lower duration and higher yield than sovereign debt. Investment grade EM companies have lower leverage (Figure 9) and offers around three times the spread per turn of leverage (Figure 8) than its US peers, making it an attractive investment destination to cross-over investors seeking to capture the EM risk premium with lower volatility.

Corporate EM IG vs US and EU IG

Section 5

EM sovereign debt

Long-term investors that are less concerned about short-term volatility already wonder whether an allocation to sovereign external debt is warranted. The investment grade part of the asset class has attractive fundamentals and offers an interesting carry. What about the broader asset class, including high yield?

In our view, overall, the asset class is very attractive for long-term investors. A simple total return back-testing exercise suggests that investing in sovereign debt when high yield spreads traded above 1,000 basis points (bps) paid decent dividends. The median return of the JP Morgan Emerging Market Bond Index Global Diversified (EMBI GD) over the following 12 months is 19.8%. The annualised returns over the following three years are 15.1%.

These attractive valuations came in the worst year for global fixed income in a century in 2022. As bonds broke the downward trend in yields prevalent since 1980, risk assets such as equities also sold off. Since around half of the contribution to the EMBI GD comes from US Treasuries and half from credit spreads, a combination of higher yields and wider credit spreads explain why the EMBI GD had its worst year-to-date returns since its inception in 1994. It is also the first time the EMBI GD has had two consecutive years of negative returns since 1994.

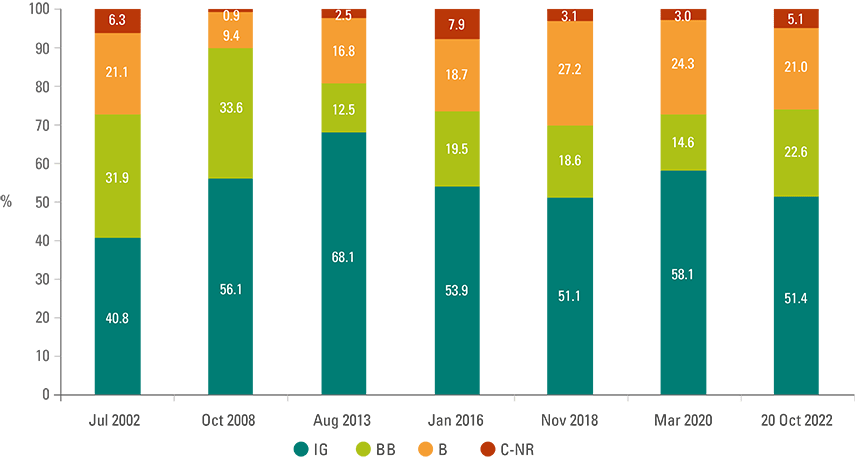

In this environment, several frontier countries dependent on the Eurobond market to re-finance their debt and fund their fiscal and current account deficits had their market access cut out. The high yield sell-off was severe, with 23 countries representing 12% of the EMBI GD trading above 1,000bps over US Treasuries, thus unable to access capital markets. The large number of countries trading at distressed levels explains why the overall EMBI high yield spreads traded at levels only seen before in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis in 1998-2001, the great financial crisis of 2008 and the Covid-19 shock of 2020. A total of 18 countries were downgraded below single-B levels, implying more than 50% odds of default within a 12-month period. When combined, these countries represent 5.1% of the index, the largest weight except for 2002 (following Argentina’s default) and 2016 (as per Figure 10).

Figure 10: EMBI GD weight by credit rating

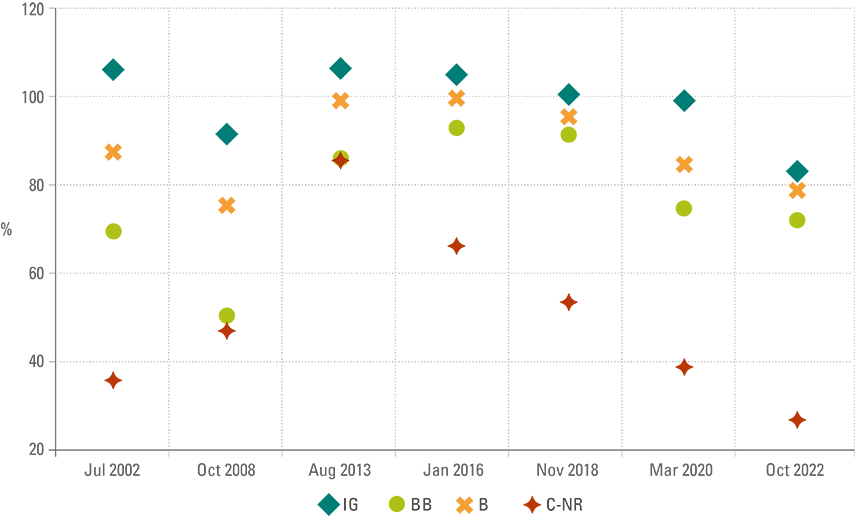

Further analysis illustrates that not all parts of the asset class trade at distressed levels. Countries rated ‘C’ or below currently trade at the most distressed levels in history, with cash price lower than in 2002 and 2008, while countries rated single-B trade at discounted levels (c. $72c), but not quite as distressed as 2008. Interestingly, BB-rated countries trade at $81c, not far from the $77c in 2008, while investment grade countries trade today at the lowest levels in terms of cash price at $85c. The price levels are illustrated in Figure 11, alongside other periods when the EMBI GD experienced an unusual drawdown: July 2002, October 2008, August 2013, January 2016, November 2018, and March 2020.

Figure 11: EMBI GD cash price by rating bucket

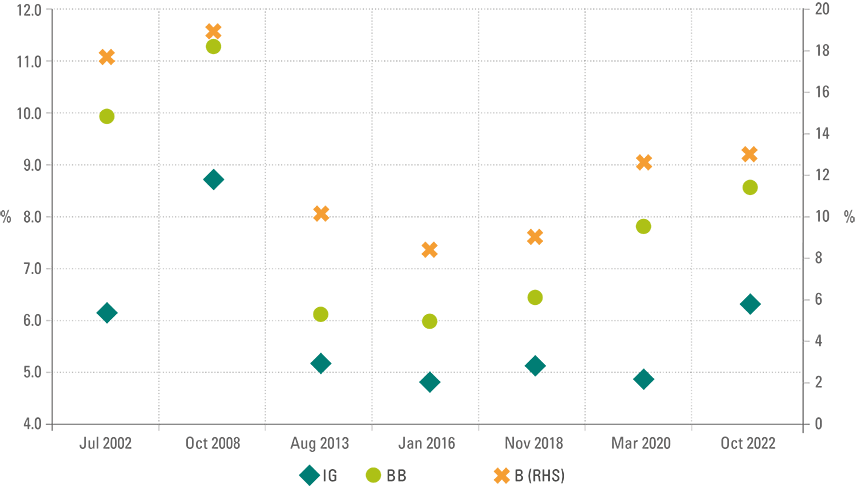

Despite the analysis above, we believe the cash price of highly rated securities may not be the most accurate way of determining value. The low cash price is simply the result of the adjustment to more normal levels of yield-to-maturity after the era of zero (or negative) interest rate and quantitative easing policies allowed these companies to issue debt at record low levels of yields. A comparison between the yield-to-maturity today and the previous drawdowns on Figure 12 offers a better yardstick to value.

Investment grade countries currently trade at higher yield levels than in 2002, albeit still lower than the 8.7% in October 2008. Figure 14 also suggests the yields on BB-rated credits look less attractive from a historical valuation perspective, trading at 8.6% today (around the widest in ten years), but lower than 9.9% in July 2002 and 11.3% in October 2008. It’s a similar story for single-B names that trade above 10%, the widest level except for 2002 and 2008.

Figure 12: Average yield-to-maturity per rating bucket

The data leads us to the following conclusions:

- Overall, the asset class is attractive for long term investors, but some segments of the high yield market are not pricing in a severe recession. High yield spreads could widen potentially to higher levels than seen this year if we have the S&P 500 trading close to 3,000 levels due to an economic recession. Most of the widening would come from BB and B-rated credits.

- Distressed countries present interesting opportunities. The average recovery value on sovereign debt restructurings is c. $59c on the dollar, while on average the C-rated and lower countries traded below $30c.3

- Long-term clients that already have some exposure to the asset class should also keep some space to increase their positions during 2023, in our view. For conservative investors, investment grade should deliver higher total returns in the short term.

Another important element in 2023 will be how countries fund their fiscal and current account deficits. For frontier countries that became overly dependent on Eurobonds, the Fed’s stance means that multilateral institutions, including the IMF, World Bank, and others, will be an important funding source. The IMF’s new ‘Resilience and Sustainability Facility’ will play an important role, particularly if the US economy does enter a recession.

Section 6

EM debt return scenarios

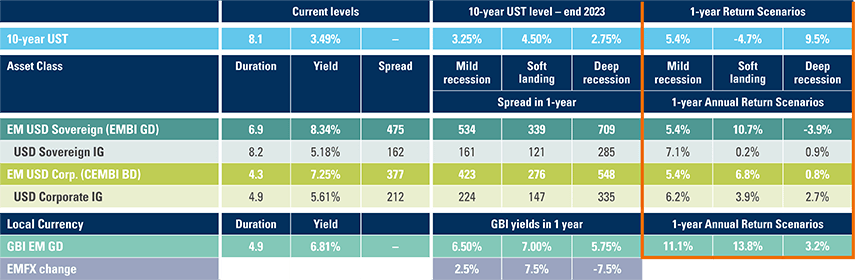

A simple total return scenario analysis on Figure 13 suggests there is significant upside for the asset class, particularly in a mild recession or soft-landing environment. The deep recession environment assumes the US hits the recession in H2 2023, when credit spreads widen to the widest levels since 2020.

- Mild recession:

- Negative payrolls in H2 2023; CPI inflation drops to 2-3% mid-year; PMIs at 38-42 levels.

- Fed hikes another 50+25+25 to 5.0%; then cuts 3x50bps in Q4 2023 to 3.5%.

- Soft landing:

- Payrolls and inflation soften slowly, growth remains positive.

- Fed hikes another 50+25+25 from here on to 5.0% and keeps it there throughout 2023.

- Overtightening + deep recession:

- Payrolls and inflation remain elevated first, then PMI plunges to low-30 levels and unemployment rises faster.

- Fed hikes another 4x50bps from here on to 6.0%; then cuts 100bps+3x75bps from Q3 2023 to 2.75%.

Figure 13: one-year return scenarios by asset class4

*Default Assumptions: Base case = average of 10yrs / bear case: worst 10yr / bull case = best 10yr (rolling 5yr defaults)

** Spread: Bear: spreads widen to covid-19 levels / Bull: spreads tighten to last 5yr lows / Base: c. 50bps wider

*** GBI EM GD: yields at 6.5%, 7.0% and 5.75% on mild recession, soft landing, and deep recession

The scenario analysis suggests:

- Sovereign debt outperforms corporate in a soft-landing scenario but underperforms if the economy hits a deep recession.

- Investment grade corporate debt outperforms investment grade sovereign on a soft landing and deep recession and underperforms slightly on a mild recession.

- Local currency bonds outperform dollar-denominated debt across all scenarios. That is contingent on the currency depreciation in a deep recession scenario or appreciation in a soft landing. We believe our scenarios are relatively conservative considering where we are in the US dollar cycle.

Section 7

EM local bonds: favourable technicals

Data from EPFR published by BNP Paribas suggested EM debt suffered USD 23bn of outflows (11% of AUM) in 2022, the worst level since 2008. EM remains underrepresented in global fixed income portfolios. EM represents less than 25% of fixed income debt, while EM bond funds account for only 3.6% of global funds. That contrasts with EM representing around 50% of global GDP. Anecdotal evidence suggests the allocation to EM is even smaller for US investors, with long-term institutional investors severely underweight the asset class in their long-term strategic asset allocation.

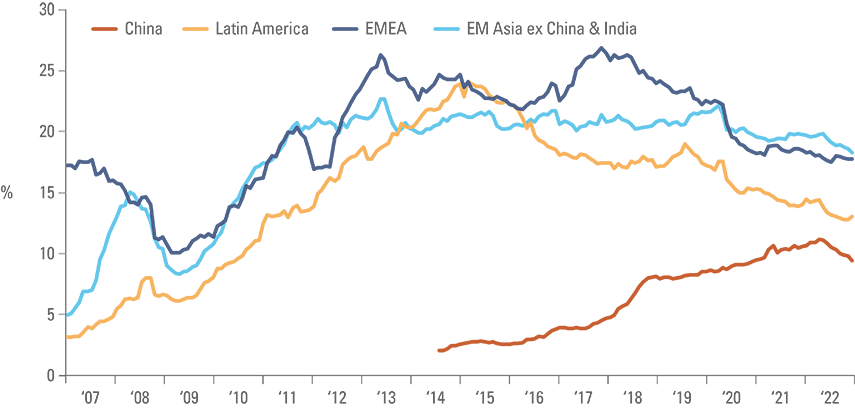

Within local currency bonds, foreign investor ownership has declined since 2013 in Latin America, since 2017 in Eastern Europe and the Middle East (EMEA) and since 2020 in Asia ex-China (as per Figure 14). The ownership of Chinese local bonds had increased from 2015 to 2021 but has declined this year from 11.2% in January to 9.4% in September.

Figure 14: Foreign investor exposure to local government bonds across EM regions

When combined with attractive valuations and more solid fundamentals (growth differential improving in EM as China reopens), light EM positioning suggests there is more upside than downside room in EM assets for 2023.

Section 8

EM equities: a year of positive inflection

In 2022, EM equities sold off on heightened risk aversion associated with geopolitical risk, reactive Fed monetary tightening and the strict Zero Covid enforcement policy enacted by its largest economy and stock market, China. While 2023 is set to see the global economic backdrop remain challenging, EM stock market performance is likely to behave very differently.

We expect to see three positive inflections next year: US monetary tightening, Chinese mobility constraints, and lower global inflation. An improvement in these global drivers should improve sentiment and allow EM equity multiples to rerate from current depressed levels. Meanwhile, EM earnings expectations have already been revised to prudent levels, which should see greater price stability and the prospect for positive surprises. This leaves EM equities well-placed to deliver strong absolute returns and to outperform developed markets.

After a period of destabilising politics in China, 2023 is expected to see greater policy impetus. This is already evident by several Covid-related policy initiatives and increased support for the real estate sector. China is no different from other countries, and an incremental period of adjustment from Covid will follow. Therefore, investors factoring in too swift a normalisation and outsized stimulus are likely to be disappointed, in turn triggering episodes of market volatility. Such opportunities should be clasped with both hands, in our view. While the steps of the Covid reopening journey remain opaque, the destination is clear.

China is the world’s second-largest economy and accounts for over one-third of global growth. It represents a significant source of consumption (40% of global vehicle sales; 25% of smartphone sales; 50% global steel demand and 15% oil demand). China is also a leader in technological advancement in manufacturing, as well as being at the epicentre of the global climate transition, given its dominance in renewables and electric vehicle supply chains. Consequently, the prospect for a China reopening is set to be a key catalyst for EM economies and stock markets in 2023.

Other EM countries will also benefit from a more resilient economic profile than DM. Economists are now estimating EM real GDP growth will outpace DM by 3%. Historically, there has been a close relationship between an expanding growth premium and relative stock market returns (as per Figure 2), and there is little reason why this time should be any different.

In Mexico, fiscal prudence and pre-emptive monetary tightening resulted in the Mexican Peso becoming one of the best performing currencies globally. Alongside macro stability, Mexico is set to benefit from accelerated nearshoring on the North American supply chain. Brazil is seeing disinflationary pressures, having significantly tightened monetary policy, which will allow its policymakers to ease monetary policy once the political risk settles. President-elect Lula’s fiscal priorities and the lagged impact of tighter domestic conditions on the more indebted lower income population bear monitoring closely.

Indonesia continues to benefit from higher renewable energy demand supporting nickel prices, and also from increased downstream processing of metals. Indonesia’s current account moved into surplus, which should support the currency and capital inflows. In Thailand, the domestic economy is recovering due to improving tourism flows, a trend that will accelerate when China opens its borders. Pre-Covid, tourism accounted for around USD 45bn (around 10% of GDP) while currently it is only around USD 3bn (less than 1% of GDP). The Middle East is befitting from structural shifts in energy supply chains, helping to finance their economic diversification efforts and fostering greater market liberalisation. As usual, domestic growth drivers are likely to dictate asset prices in several small EM and frontier market countries: economic reforms and institutional progress is expected to continue in Vietnam and Morocco and the prospect of structural monetary reforms in countries like Egypt and Argentina brings opportunities.

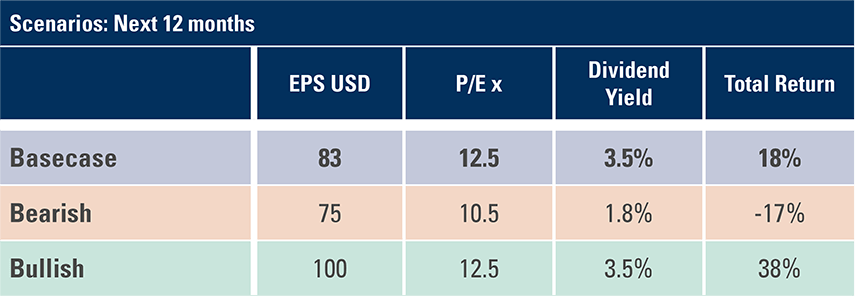

After the longest market drawdown in history, investor positioning in EM equities is light. The MSCI EM Index trades around 11.0x forward earnings, which is below its long-run average of 12.5x. Meanwhile, 2023 earnings growth expectations are prudently in the single digits, after declining by around 15% from its highest levels in 2022. Encouragingly, there is increasing evidence of EM corporates cutting costs and maintaining capital expenditure discipline. Thus, margins can expand in 2023 as higher revenue growth led by increased demand combines with lower costs.

A conservatively base case scenario assumes the current dividend yield of 3.5% and EM multiples rising to 12.5x earnings, leading to ‘high-teen’ returns in 2023 as per Figure 15. As always, the heterogeneity of EM means that active management remains key.

Figure 15: Scenario analysis: EM equities returns

Section 9

Several EM countries are well positioned to navigate a challenging 2023

Countries and companies with low debt levels will offer a haven in an environment where interest rates volatility is larger. Furthermore, countries that did not experience a real estate boom fuelled by low mortgage rates will be in a better position to navigate the incoming bear market in real estate. Not surprisingly, Mexican, and Indonesian assets have been benefiting from a much more stable environment – these countries have the lowest levels of debt to GDP amongst the largest countries in the world. Affordable housing is also positive for social stability, lowering the propensity for populist movements and policies.

Countries that are neutral to geopolitical conflicts will benefit from trading across both sides of international conflict. India, for example, has not only been purchasing a much larger volume of energy from Russia at a discount, but has benefitted from western companies investing in manufacturing and the IT service industry onshore (i.e., Apple announced a new manufacturing plant in India).

Countries with low labour cost, reliable energy and a favourable regulatory environment are likely to benefit from friendly shoring of manufacturing. Vietnam was the main country beneficiary from this trend, but Bangladesh, Indonesia, India, Thailand, and Mexico are also on the radar. Indonesia and India are working to become powerhouses of renewable energy, the former building an electric vehicle batteries hub and the latter boosting solar and wind energy capacity at a fast pace. These countries are also likely to retain access to lower cost fossil fuels from Russia. Countries with large consumer markets like Brazil and Colombia are also likely to attract more investment in manufacturing dedicated to their own local markets.

The Brazilian energy matrix – with more than 80% of energy produced by renewables (hydroelectric, wind and solar) – stands out as a winner. Food self-sufficiency has also proven to be a fundamental strength. Brazil produces 10% of the world’s food and is also a powerhouse in the mining of industrial metals which will be important for energy transition. President Lula may be keen to spend more on social initiatives, but he is also keen to exploit these Brazilian inner strengths. Also, if the world is serious about shifting its energy matrix towards more renewable sources, large investments in transmission and generation will boost demand for Chilean and Peruvian copper.

Section 10

Fiscal policy

Will the Republican Party force a faster fiscal consolidation by not increasing the US debt ceiling? In our view, the risks of tighter fiscal policy increased after the Democrats lost control over the House of Representatives, even if they did so by a very small margin. Should this scenario materialise, it would be a negative event for the US dollar and US assets as a tighter fiscal policy would have a negative effect on growth, particularly if the tightening is caused by dysfunctional politics, rather than a thoughtful fiscal consolidation.

Fiscal policy will also be extremely important across all countries, particularly those with elevated government debt to GDP ratios. In a world where higher inflation brings interest rates significantly above zero, the ‘bond vigilantes’ have regained their ability to disrupt the normal functioning of government bond markets, causing higher volatility across capital markets, including currency, private credit, and equity valuations. The events in the UK in September 2022, and the volatility in Colombian and Brazilian markets post-presidential elections, were a tell-tale warning that irresponsible fiscal policies will be punished, both in EM and DM countries.

Section 11

Global debt and real estate

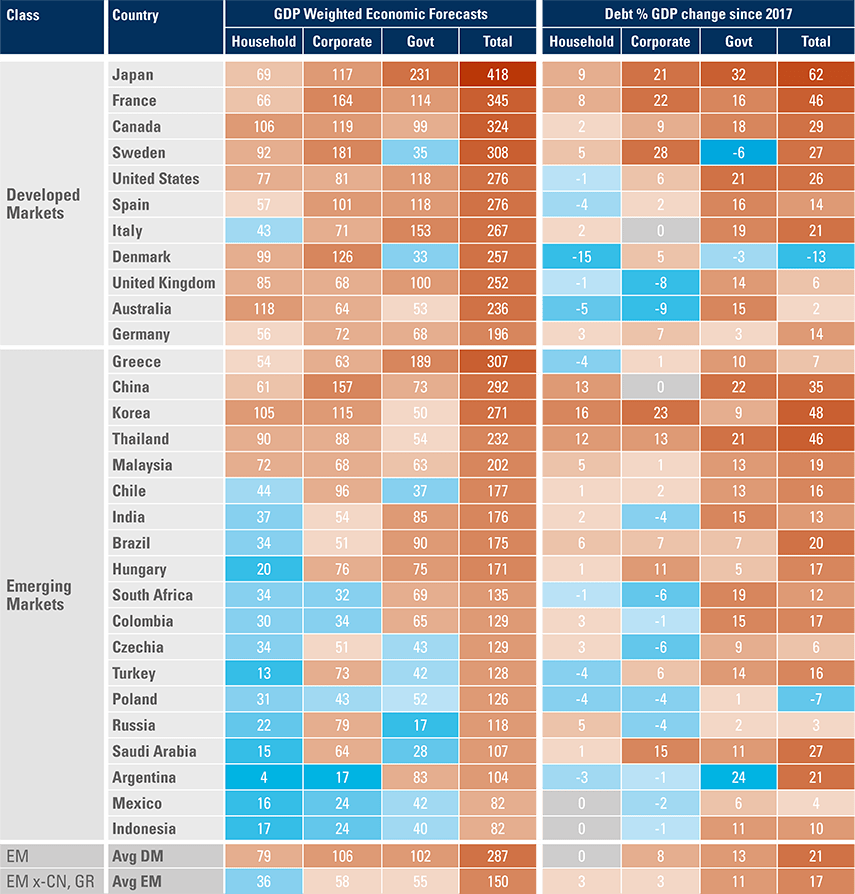

We also believe higher interest rates will keep house prices under pressure. House prices are likely to decline the most in countries where household debt to GDP is elevated, where house prices have increased because of higher debt over the last five years, and where interest rates have increased meaningfully.

A housing downturn impacts the economy via the credit channel. Tougher lending standards leads to lower sales, declining housing prices, and less construction. Crucially, housing is the single largest asset in the household sector across most OECD countries.5 Therefore, a recession in the real estate sector has a larger impact on household wealth than lower stock prices, depressing sentiment and directly impacting disposable income via higher mortgage payments once those transactions reset. In our view, the change in mortgage rates is likely to bring US house prices down at least between 10%-20% next year and housing represents 37% of the US household wealth, according to the OECD. UBS estimates a 15% decline in US house prices would bring global GDP growth down by 1%.

Figure 9 shows Canada, Australia, and Scandinavian countries look particularly exposed to a downturn in global housing. The US household balance sheet may be less exposed than in 2007-08, but there has been a sharp increase in US house prices over the last five years. In EM, only South Korea, Thailand and Malaysia has large level of indebtedness in the household and corporate sectors, but interest rates have not increased at all in China and barely increased in Thailand. The EM corporate sector has elevated levels of indebtedness in China, Chile, and Hungary, according to the BIS data.

Figure 16: Debt/GDP across sectors by country

Another sector facing headwinds is office real estate. There in increase pressure from employees to have more flexibility to work from home for longer. This is likely to increase demand for more flexible office spaces and may lead to less demand for office space. Moreover, the capital structure of office real estate typically relies on large amounts of debt to boost the return on equity. As debt deals get rolled over, higher interest costs will lead to higher costs when demand for office space may be declining. This may complicate the transition from rigid office spaces to flexible ones, and from offices to apartment blocks. Private equity and illiquid portfolios will also be challenged in a recessionary environment.

Section 12

Geopolitics

China

Was the self-imposed economic slowdown in 2022 a political accident or astute economic management? We may never have a final answer to this question, but it is hard to dispute that the timing of Chinese mobility restrictions was fortunate, from a macroeconomic perspective.

China is the only economy in the world that didn't experience any inflationary pressures in H2 2021 and 2022. We believe the low levels of inflation in China are related to the demand destruction engineered by the real estate crisis and the mobility restrictions imposed by its zero Covid-19 policy. Lowering demand is the appropriate policy decision, from a macro perspective, in a world where supply constraints and excessive demand for consumer goods have been putting pressure on prices. This means that, as the largest economy in the world goes into recession in 2023, China can afford to reopen its economy without generating pent-up inflationary pressures.

Most importantly, China will relax mobility restrictions during 2023, boosting GDP growth. This single factor means GDP growth is likely to recover in China, bringing the country to a very different position than the US, Europe, and Japan next year.

A few weeks after the 20th Party Congress, the Chinese leadership announced 20 measures to moderate mobility restrictions. At the time of writing, the politburo had just placed added emphasis on irreversible reopening of the economy and pledged to stabilise growth, employment, and prices. There was no mention of “zero covid-19” or “houses are for living, not speculating”, instead, the politburo focused on “enhancing market confidence”. Better mobility will drive consumption higher and allow for a normalisation in the real estate market, a sector where the government’s liquidity restrictions have been eased as the central government actively promotes more credit to the sector.

The real estate crisis is a real threat to the economy, and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) needs the private sector to support the economy. Taking a step back, the clashes with capitalists started with big tech regulation – some of it thoughtful, some of it political, in our view – in Q4 2021. The news that Chinese regulators have approved games after a 17-month drought and the USD 1bn fine on Jack Ma are potential signals that the leadership has found a new equilibrium with the sector. Several companies have been controlling costs effectively and showing they have operational autonomy, even if operating under political pressure in a slowing economy.

China also announced 16 measures to re-establish confidence in the real estate sector. In more simple terms, authorities adopted three measures allowing the real estate sector to rebound: incentivising banks to extend the maturity of debt to developers; setting up programmes to deliver fresh funding to good developers; and more recently bringing in state-owned companies to buy large equity stakes at private developers.

Over the medium to long term, China’s most important economic reform in our opinion is to rebalance its economy. Chinese GDP growth became over-reliant on investment and net exports over the last three decades and despite all the talk, any rebalance proved elusive. To boost consumption, China needs to reopen its economy, stabilise the labour market and, most importantly, increase wages. This means several loss-making unproductive companies will likely go out of business. The impact could be absorbed by a new round of privatisation of inefficient state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Several are owned by local governments, which are themselves bloated and inefficient. Implementing these economic reforms should mean the potential GDP growth in China would be much lower, but also more sustainable.

Taiwan and semiconductors

Semiconductors are one of if not the most important conduit to technological development. China's fast progress from low value-add manufacturing to the frontier of the technological development (artificial intelligence, supersonic weapons, robotics, 5G technology, etc) allowed it to keep developing, but also set it on a collision course with the largest economy in the world. The willingness of the US to keep its economic and military hegemony shifted the relationship with China from cooperative to confrontational. The fact that most Americans have a negative view of China, and most Chinese have a negative view of Americans, suggests this rivalry will remain in place for longer.6

The US legislation restricting Chinese access to advanced semiconductors is a most direct form of aggression made towards China, and is much more important, from an economic perspective, than Trump's misguided trade war, in our opinion. The key question is whether restricting access to one of the most important technological components in the world will leave China with no alternative but to invade Taiwan.

This question is very hard, if not impossible, to answer. First, it is likely that China was already stockpiling high-end semiconductors in preparation for a possible embargo, which would help to explain the extraordinary demand and shortage of chips over the last few years. The US would have a much higher incentive to defend the island of Taiwan before TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) has ramped up capacity to produce the most advanced 3- to 7-nanometre chips in its Arizona fabrication facility, likely to be complete by 2024-25 and ramped up by 2026-27.

Notably, several South Korean suppliers received a one-year waiver to keep operating with China.

Finally, China may also be unsure of its own military capabilities, particularly after the poor performance of the Russian army in Ukraine. Nevertheless, the risk of an invasion was meaningfully increased by the aggressive restrictions in the chip industry, a factor that may overhang the valuation of Chinese assets for longer.

On the other hand, a contrarian could point out that 2023 offers a rare (and brief) window for de-escalation of tensions between US and China. The absence of US elections until Q4 2024, and the economic challenges faced by both US and China, may encourage both parties to de-escalate tensions and seek more cooperation in the short term. This is far from priced into asset prices today and could have important asset allocation implications as most global investors remain underweight Chinese assets.

Ukraine

As the war approaches its one-year anniversary in February 2023, questions over the next phase become more pressing. Will we see a ceasefire or a frozen conflict? Ukraine gaining territory on the ground increases the likelihood of a ceasefire, but also escalation. Most ceasefires happen when one or both sides of the conflict cannot make more progress on the ground and decide to settle. As the West debates what a Ukrainian victory looks like, Ukraine is holding its stance that victory means retaking its entire territory, including Crimea. This is dangerous as losing Crimea is existential to Putin and would probably lead to escalation.

However, Russia still believes time is on its side and Western support will "crack". This seems to be somewhat backed-up by several high-profile Republicans who have been fighting the notion that the US must permanently support the war in Ukraine. Kevin McCarthy – expected to become the next Republican Speaker – has said there is “no blank check”, but bipartisan support for Ukraine remains. Even if US support weakens, the legislation already approved provides significant support over the next few years. Congress was discussing additional aid worth USD 37.7bn on top of three packages adding to USD 68bn already approved, of which only around 10% was spent in 2022.7

Overall, the war is likely to remain in its current shape well into the winter. This is a scenario that will need reassessment in early spring.

It is increasingly clear that Russia lacks the ability to fight a Ukraine armed by the West on the ground and has therefore opted instead to destroy the country’s infrastructure. Eventually there will be an incentive for both sides to seek a ceasefire, allowing for the reconstruction of Ukraine, alongside the return of immigrants to the country. The normalisation of energy flows will involve a tricky negotiation, but a ceasefire would at least allow for an end to ongoing sanction escalations.

Turkey

Turkey has been a key broker between Russia and the West in 2022, mediating the important deal that allowed Ukraine to export food out of Odesa earlier in the year. At the same time, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan has adopted a more conciliatory tone across the Arab world, shaking hands with the Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, despite his former support for the opposition Muslim Brotherhood. The more conciliatory approach is most likely part of a broader agreement to get much-needed funding from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Turkey faces a general and presidential election in 2023, with Erdogan trying for re-election after leading the country for more than two decades. It is unlikely he can win elections in the first round as his AK Party has around 36% of vote intentions, a small improvement from its lowest levels, but still not enough for outright victory. In preparation, Erdogan has been replenishing Turkey’s dollar liquidity, borrowing money from Saudi Arabia and Qatar, as well as issuing three Eurobonds over the last six weeks as risk appetite improved. This should allow for increasing expenditures going towards the elections to reboot his popularity. Nevertheless, Erdogan may still lose, should the popular mayors of Ankara and Istanbul campaign at the national level on a unified ticket.

Turkey has significant geopolitical strengths which can be monetised, particularly if more credible economic policy is installed after the opposition returns to power. However, a decade of heterodox economic policies has led to a severe deterioration of the country’s foreign exchange reserves. Turkey has also accumulated significant foreign debt and several off-balance sheet liabilities may become clearer after the elections. Therefore, a foreign debt restructuring should not be discarded if Erdogan remains in power. If the opposition wins, a honeymoon period could allow for a significant improvement of the country’s asset prices which may not be sustainable.

Venezuela

The US is under significant pressure to strike a new balance in its relationship with Venezuela. The tight oil market resulting from the war in Ukraine and the record migration of Venezuelans to Colombia, the US, and other South American countries, has made the situation more urgent.

In November, the White House allowed Chevron to invest in exploration and production of oil in Venezuela, and export the production to the US, with the condition that profits don’t reach the Venezuelan national oil company Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). There is a renewed hope that the US administration could work with current President Nicolas Maduro and active discussions at think-tank levels suggest that the reopening of Venezuela's oil market could take place in a special arrangement (i.e., money going into an escrow account for humanitarian purposes).

It is often mentioned that Biden will struggle to work with Maduro, considering the opposition by influential members of the Republican Party in Florida. Counterintuitively, Biden could feel liberated to work again with Maduro now that the Democratic Party has already lost a significant portion of the Latin votes in Florida to Governor Ron DeSantis.

Section 13

2023 political calendar

The electoral calendar will be relatively light in 2023, but this is not to say that politics won’t matter. The key events in Q1 are the presidential election in Czechia on 14-15 January and the Nigerian general election (25 February).

Nigeria

It will be interesting to see whether Peter Obi, running for the Labour Party, can deliver a surprising victory against former governor of Lagos state Bola Tinubu and former vice president Atiku Abubakar. Tinubu is running for the incumbent All Progressives Congress (APC) while former vice president Atiku Abubakar is running for the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). Obi has a good track record as the governor of the Anambra province and his relatively youthfulness brings hopes for a change in scenery for young Nigerians, who enthusiastically call themselves “Obi-dients” in support for the young governor. Tinubu has long been a kingmaker and well-known figure within the APC while Abubakar has contested the presidential election five times (1993, 2007, 2011, 2015 and 2019). Both Abubakar and Tinubu are seeing to be better-equipped to manage the country than incumbent Muhammadu Buhari, but represent the traditional elite of the country.

In Q2, both the Thai and the Turkish general elections will be important events to monitor in EM, while regional elections in Spain are likely to be as noisy as usual in Europe.

Thailand

Thai general elections are tentatively scheduled for 7 May 2023 but could be called sooner. The coalition formed by the main opposition Pheu Thai Party leads opinion polls, followed by the governing Move Forward Party, but neither party are expected to have an outright majority in Congress. Hence, most likely there will be a need for another wide coalition to form a government, lowering the risk of any meaningful change in economic policy.

The Bangkok Post recently reported General Prayut Chan-o-cha saying he was able to remain in the prime minister post until 2025. The Constitutional Court said Prayut had not reached the eight-year length of service allowed by Thailand's 2017 constitution, and technically allowed him to stay in power for another two-years. Prayut became prime minister in 2014 following a coup, but he has been prime minister under a new constitution since Jun 2019. The Constitutional Court ruled that the count should begin in Apr 2017, when the new constitution was promulgated.

The reopening of the Chinese economy will play a much more important role for Thailand as tourist arrival may get close to 28 million in 2023 (71% of pre-Covid levels), from 11 million in 2022, according to Nomura. The inflow of Chinese tourists keen to enjoy a relaxing holiday after three years of lockdowns will be very important.

Turkey was covered in geopolitics.

In H2, the main elections to monitor will be Argentina’s presidential election as well as the Pakistan general election, both of which are due to be held in October.

Argentina

It is very likely that the opposition coalition (Together For Change) will return to power in Argentina in the next general election, due to be held in October 2023, after Mauricio Macri’s disappointing defeat by Alberto Fernandez in 2019.

Despite a successful debt restructuring which provided significant relief to the sovereign, the Fernandez administration’s unsustainable economic policy has resulted in hyperinflation and severe distortions in the foreign exchange (FX) market, making the ruling Peronist coalition highly unpopular. Unlike the Macri administration, the next government of Together for Change will likely have control of both houses of Congress, making it easier to implement their policy initiatives.

There seems to be a strong political consensus within the opposition coalition for immediate and decisive economic policy adjustments and structural reforms, led by significant fiscal consolidation once they take office. Such actions will likely address the imbalances and distortions faced by the Argentine economy, restore macroeconomic stability and confidence of foreign and local investors, unlocking new investments. The new government will also likely get a boost from an increasingly efficient oil and gas industry, which will benefit from new infrastructure currently under construction to fundamentally change the energy trade balance of the country.

Nevertheless, the road of transition to the new government will be rocky. The current administration has restored a fragile stability after appointing Sergio Massa as the Economy Minister, but risks of a full-blown economic crisis remain, which could be triggered by factors such as a depletion of FX reserves, inflation surging to well above 100%, or a run on bank deposits. However, should such a crisis occur, will most likely bring a more convincing victory to the opposition, making it easier for the new government to carry out necessary policy adjustments.

Pakistan

General elections will be contested by August 2023. Parties forming the current coalition government between Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League Party (PML-N) and the Bhutto family’s Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) will be up against the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) led by former Prime Minister Imran Khan. The two first parties have been the bedrock of Pakistan’s traditional politics that Khan looked to disrupt.

In the last election, Khan’s party won most seats in congress, but was short of a majority, demanding a coalition with smaller parties. The military, a traditional stabilising power between political parties, was seen as instrumental in allowing Khan to become Prime Minister. When the Ukraine war drove oil and food prices higher, Khan’s government lost its parliamentary majority and was replaced by the current coalition government led by Sharif.

It is unclear whether the PTI will win the next elections as political tensions have been elevated in 2022. The current government has struggled to take unpopular macroeconomic decisions as devastating floods led to a humanitarian crisis on top of its balance of payments issues.8 The IMF is due to undertake the ninth review under the current programme, which may be delayed and completed alongside the tenth review due in Q1 2023. The main sticking points are believed to be the IMF’s request for the government to increase taxes to compensate for lower than targeted revenues because of the economic recession, and to see an itemisation of flood relief spending aid.

Multilateral institutions, including the IMF and China are Pakistan’s largest creditor groups, with approximately USD 42bn and USD 27bn of outstanding loans respectively. Pakistan is a key country in China’s Belt and Road initiative and is seen as a key ally of China in its contentious geopolitical relationship with India. The ability of Pakistan’s new government to stabilise the social situation and strike a balance in negotiations with both China and the West will be important for the eventual recovery of its USD 7.8bn of outstanding Eurobonds, equivalent to less than 2.5% of the country’s GDP.

In Eastern Europe, Ukraine is scheduled to have parliamentary elections in October, while Poland is running parliamentary elections in November.

Appendix

The Fed’s policy mistake and reasons for a 2023 recession

The Fed is on a mission to bring the year-on-year (yoy) rate of inflation lower, tightening monetary policy at the most aggressive pace since the early 1980s, as Fed Chair Jerome Powell tries to revive the inflation-fighting policies of former Chair Paul Volcker. In our view, there are several problems with Powell’s approach.

Historical background and economic structure

Volcker was appointed after a decade when inflation was above nominal interest rates most of the time. Decades of negative real interest rates eroded the value of the debt accumulated in the Vietnam war. Today, the global economy is overindebted after the largest global fiscal expansion since World War II. Too much debt means policy rates cannot be hiked above inflation without major consequences.

Furthermore, Volcker’s tightening came after a decade of high commodity prices when energy exploration and technology investments thrived. That’s the period when Brazil developed its ethanol programme powering cars with sugar cane-refined fuel instead of oil-refined gasoline. High investment in energy boosted the supply of energy, setting the stage for a bear market in commodity prices that lasted three decades.

In contrast, commodity prices have declined drastically over the last decade, with West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil futures trading at negative levels briefly in 2020 as storage capacity were overwhelmed in Cushing, Oklahoma and traders couldn’t take delivery in their expiring long future contract, forcing them to sell oil in the market at any price. Recently, the willingness to accelerate the energy transition led several investors to withdraw capital for the fossil fuel industry, responsible for around 80% of global energy consumption.

Policies designed to reverse inequality post-Covid (income transfers, more bargain power to unions, student debt forgiveness, etc) led to an increase in demand for commodities. The energy transition is boosting demand for industrial metals. Finally, the Russian invasion of Ukraine led to food scarcity as the unintended consequences of the sanctions levied on Russian energy exports accelerated the trend of higher energy and fertiliser prices. The second year of this major commodity shock should itself lead to lower demand for discretionary goods and services and, therefore, lower the need for monetary policy tightening.

Central bank credibility

It was clear that inflation in 2021 was not transitory. We were discussing structural dynamics leading to more inflationary pressures already in Q4 2021. The central banks of Russia and Brazil were increasing policy rates already in Q1 2021, citing demand-led inflationary pressures as the service sector of the economies were shut and the lavish income transfer led to exuberant demand for online products, electronic goods, and other discretionary spending.

The belief in transitory inflation was, in our opinion, a mistake promoted by the Fed and adopted by most DM central banks around the world. The videos of US Congressmen – usually not interested in ‘wonkish’ monetary policy debates – accusing Powell of the inflationary pressures observed in the economy spoke volumes. Even more impressive was how Powell decided to re-incarnate Paul Volcker, quoting him abundantly as he tightened the monetary ratchet.

In our view, the credibility of DM policymakers is likely to take another hit as the current policies are very likely to lead to an economic recession, unemployment, and discontent. If our view is right, we shall soon watch Powell sweating to answer another round of questioning in Congress, this time facing accusations of overtightening.

Why do we expect a recession? Monetary policy dynamics

Monetary policy operates with meaningful lags, as discussed in our recent weekly research pieces. Therefore, the current 7.7% yoy rate of inflation is the result of excessive monetary and fiscal stimulus from Q2 2020 to Q2 2022.

The Fed’s only tool is to bring demand lower, but the transmission channels are indirect and imperfect. As the Fed hikes rates and sells assets from its balance sheets, we are watching:

- Borrowing cost rises leading to less investment, lower housing demand and reduced consumption.

- Lenders turning more risk-averse, lifting the yield on loans even more than Fed Fund rate increases and becoming more selective on credit quality.

- Investors also becoming more selective, selling less secure assets (equities > high yield debt > foreign assets) in lieu of assets with perceived lower risk (government bonds > bank deposits > local assets).

- Companies focused on growth with negative cash flow coming under distress, forcing them to downsize by firing employees, while even high-quality large companies freeze hiring.

- Asset price sell-offs hitting sentiment, which in turn hits consumption.

- Apropos, leading indicators such as recent PMIs suggest Europe is already in recession and the US is moving fast towards this direction.

These dynamics have already led to severe distress in asset prices. The Fed is already breaking things:

- Several frontier countries dependent on Eurobonds to finance their fiscal deficits have lost market access, leading to balance of payment crises from Sri Lanka to El Salvador.

- Pound Sterling (the world’s former reserve currency), and UK Gilts broke down following a misguided fiscal expansion.

- Credit Suisse credit default swaps (CDS) widened significantly after the market decided to wait and see whether Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni would follow Hungary in defying the European Union.

1. EM: Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czechia, Egypt, Greece, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Uruguay, and United Arab Emirates.

The forecasts do NOT include Argentina, Turkey, and Ukraine to eliminate outliers which would distort the analysis.

DM: United States, European Union, Japan, United Kingdom, Canada, and Switzerland.

2. Treasury General Account (TGA) and Reserve Repo Facility (RR).

3. See https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36877

4. *Default assumptions: base case = average of ten-year/bear case: worst ten-year/bull case = best ten-year (rolling five-year defaults).

** Spread: Bear: spreads widen to Covid-19 levels / Bull: spreads tighten to last five-year lows / Base: c. 50bps wider.

5. See https://www.oecd.org/housing/policy-toolkit/data-dashboard/wealth-distribution

6. See https://www.gzeromedia.com/the-graphic-truth-how-do-chinese-people-view-america

7. See https://www.csis.org/analysis/aid-ukraine-explained-six-charts

8. See https://www.who.int/emergencies/situations/pakistan-crisis