NEW SERIES: Live at the Sub-ICs

Insight into areas of research focus at our Equity Sub-Investment Committees (ICs) which are responsible for managing Emerging and Frontier Markets strategies.

Vietnam is often regarded as a ‘poster child’ for developing nations, offering a wealth of investment potential. This is with good reason, given several structural growth drivers are underpinned by attractive demographics, a young, well-educated, and low-cost workforce, as well as an advantageous strategic geographic location. These advantages have seen Vietnam emerge as a leading logistics and manufacturing hub and one of the world’s fastest growing economies. In 2022, Vietnam’s real gross domestic product (GDP) growth was 8.0%. These positives, however, have not been reflected in stock market performance. The local index is 40% down from its 2021 year-end highs in US dollar terms.

Such a dichotomy has highlighted several challenges facing Vietnam, with learnings for other Frontier Market (FM) countries and smaller Emerging Markets (EM). It has also triggered three Ashmore research trips to Vietnam over the last 12 months.

This paper brings readers into the discussion on the health of Vietnam.

Question 1

What factors caused the loss of confidence in Vietnam?

We believe the principal trigger was policy making which was designed to strengthen Vietnam’s rule of law over the long term, but provoked unintended headwinds to business and consumer confidence in the short term. ‘Policy immaturity’ can be a common source of temporary market volatility in FM economies as they look to undertake transformative socio-economic as well as macroeconomic journeys. Such episodes can create significant investment risk, as well as opportunity. In Vietnam’s case, it appears that several policy initiatives combined to cause a largely self-made confidence shock, which was exacerbated by the deteriorating global macroeconomic backdrop. These policy initiatives included:

- Since 2018, a broad-based anti-corruption campaign has been targeting bribery cases, corporate bonds, real estate deals and even Covid-related funds. This campaign has embroiled several listed companies, resulting in high-profile arrests and unsettling headlines.

- The introduction of ‘Decree 65’: new rules for Vietnam’s nascent domestic corporate bond market were designed to deliver a more transparent and sustainable market. The rules included reducing the ability of real estate developers to take speculative positions with excessive leverage on undeveloped land. While the rules are well intentioned, the policy has served to exacerbate already-tight domestic liquidity.

- At the same time as the deterioration in global macroeconomic conditions, the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) tightened domestic monetary policy to protect the Vietnamese Dong (VND) and to support price stability.

Question 2

What is the health of Vietnam’s domestic economy?

Vietnam is one of the fastest-growing economies in Asia, if not the world. The country's economic boom is attributed to the shift in labour allocation from agriculture to the manufacturing and services sector. Vietnam also benefits from strong private investment, tourism, wage growth and increased urbanisation. It has positioned itself successfully as a competitive and high-skilled manufacturing hub. For example, it is home to Intel’s largest semiconductor assembly and testing factory. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) disbursement reached circa USD 18bn in 2022, which is high double-digit growth year-on-year.

Through 2022, Vietnam’s economy remained in good shape, bouncing back from its only real COVID-related lockdown in late 2021/early 2022 and posting 8.0% real GDP growth. Corporates reported healthy and consistent demand, while household budgets were not weighed down by significant indebtedness and were therefore equipped to cope with higher interest rates. Domestic banks were not under undue stress either.

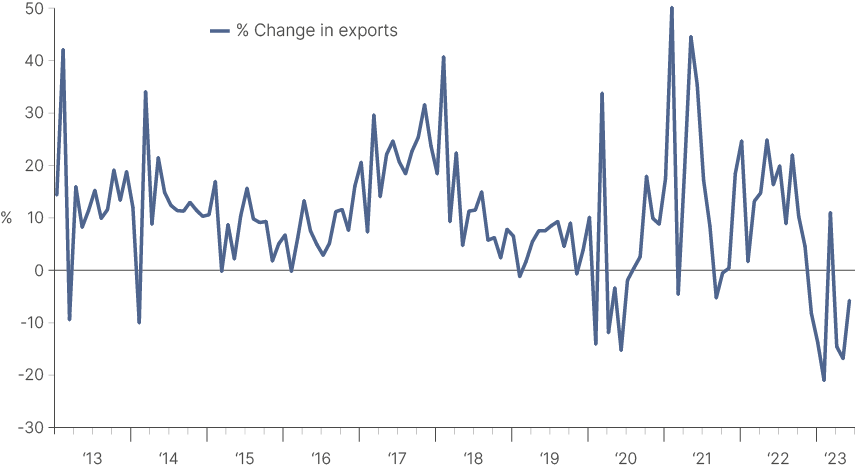

This favourable backdrop deteriorated from the end of 2022. Vietnam’s strong external trading links became a headwind given decelerating global growth and disrupted Chinese supply chains. The domestic corruption purge continued unabated with more arrests, while tighter regulations for corporate debt and real estate drained domestic liquidity. Vietnamese exports began to fall by double-digits year-on-year, with imports slowing too. The result was a cut in worker hours, and job losses saw workers leave the cities to return to their families in rural communities. Several real estate projects suffered significant delays, resulting in failed unit deliveries and some fire-sale prices. Confidence fell across the economy.

Figure 1: Vietnam’s exports year-on-year

Question 3

Is there a serious risk of a credit event?

Vietnam, like many other FMs, has its own institutional idiosyncrasies which need to be recognised. In Vietnam’s case, this includes having a central bank-controlled credit quota system, meaning credit supply in the economy is not a function of banks’ willingness and ability to lend and satisfy credit demand. This is a notably cautious approach and is designed to avoid credit driven boom-and-bust cycles, as well as to minimise the inflationary impacts of credit expansion. What it also means is there is not enough credit to satisfy all of the demand.

This ‘structural credit scarcity’ is being even more acutely felt given the new corporate bond rules (see above), which are slowing new debt issuance. There are approximately USD 6.2bn1 of maturities coming due in 2023 which is greater than the credit growth we have seen in relation to the real estate industry. While we do not see a systemic risk of a market-based credit crunch, given the system is central bank-controlled, this does put some developers – and parts of the real estate market in particular – at risk.

Question 4

Should we expect a policy response?

Vietnam is a one-party Communist state, yet its economy is managed on a capitalist and democratic footing with some similarities to Singapore, for example. The recent uncertainty, illiquidity, and political noise may have peaked with the resignation of president-figure Nguyen Xuan Phuc in January 2023, who departed along with other officials. The decision was orchestrated by the 16-member politburo that governs Vietnam and is chaired by the Party General Secretary. By February, the government had implied that steps would be taken to ease liquidity problems, while the corporate bond legislation, highlighted earlier, was softened under Decree 8. The government also reaffirmed its commitment to invest in the infrastructure of the economy.

It is not yet clear whether this ‘solves’ Vietnam’s political uncertainty. Several planned provincial appointments could provide a clue about the country’s future direction. These appointments may also empower those in office to move forward with renewed budget spending and the granting of new land permits, both of which are much needed, in our view. We expect Vietnam’s authorities will likely allow companies to muddle through with generous regulation and by continuing to adjust the policy mix, yet based on the government’s track record, it may not be in a hurry to do so.

Question 5

How will this impact Vietnam’s economic outlook?

The good news is that, in our view, Vietnam is not ‘broken’. While GDP growth for 2023 will not match the level seen in 2022, currently the ‘weak’ consensus estimate for calendar year 2023 growth is still an enviable 5.8%, and World Bank estimates put growth at 6.3%. Double-digit credit growth is expected to continue and FDI should continue to grow each year, and the government is expected to eventually spend most, usually 80%, of its investment budget. Inflation looks to have peaked at 4.9% and the SBV became the first Asian central bank to ease monetary policy in April with a 100 basis point cut in rates to 5.0%, followed up by another 50 basis points cut in June. The SBV has also made it clear it feels the risk of higher inflation is low, and that the economy needs support to drive growth.

The VND has remained stable over the past year, devaluing just -2%, and is flat for the year-to-date. The current account balance was just a 0.2% deficit in 2022 and should be in surplus in 2023, driven by a rebound in inward tourism, in our opinion.

The outlook overall, though, remains challenging. Even the more optimistic market participants are only expecting a recovery in domestic demand to start in Q3 2023. This is mostly predicated on macroeconomic improvements in the developed world, which itself remains an uncertain outcome.

Question 6

What is priced in to Vietnam’s stock market?

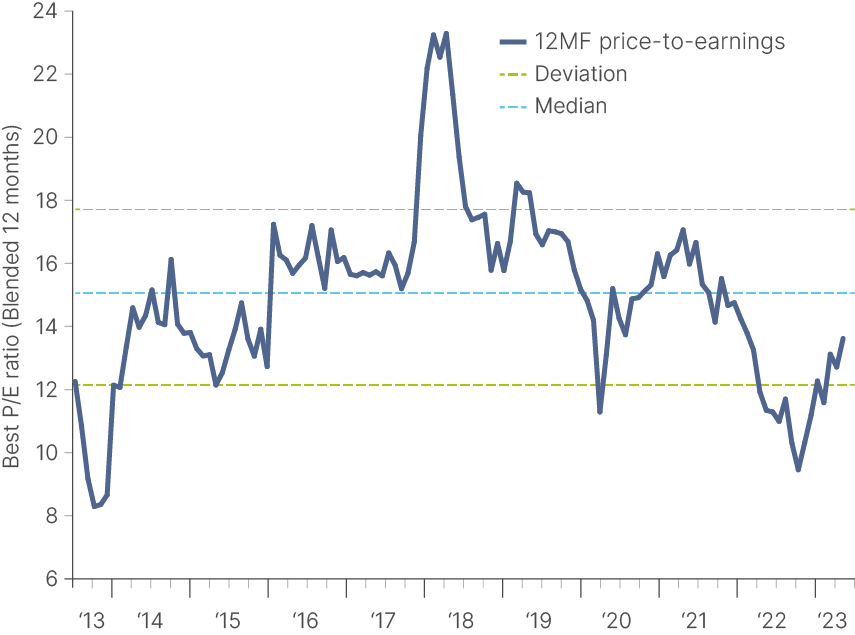

Despite the deterioration in macroeconomic fundamentals, everything has a price. The Vietnamese market de-rated briefly below 10x price-to-earnings, the lowest level since Vietnam’s financial crisis in 2013, before staging some recovery. However, Vietnam’s current challenges are very different to those of a decade ago, as today’s issues are policy driven, and its banking system is more robust this time. Moreover, we believe there will be buyers willing to support the real estate sector when the liquidity situation and the policy mix allows it.

Figure 2: MSCI Vietnam forward price-to-earnings

FY2023 earnings expectations have fallen 20%, although we expect large variability around this figure, with banks probably reasonably placed, while consumer and real estate companies could suffer a larger hit to demand and earnings.

By market sector, and even within sectors, there are important differences. The outlook looks tougher for real estate companies without land permits and with inventory issues, yet others can operate as normal. Banks with high corporate bond and real estate developer exposure could struggle, yet the regulations allow for a slow and steady realisation of any losses with plenty of opportunities to restructure. Meanwhile, consumption demand is under pressure given the headwinds of higher inflation, higher rates, lower working hours and higher unemployment. Several consumer companies are also battling heightened competition and higher input costs, although structurally-strong consumption drivers remain formidable for those better-placed companies.

Conclusion

The behaviour of Vietnam’s stock market over the past 18 months is a reminder of the volatility of single-country FMs and smaller EMs Despite long-term structural drivers remaining intact, there are periods where equity markets might not perform. We feel Vietnam’s current difficulties should not detract from an essentially and fundamentally strong outlook for a wide range of other FM iand smaller EM markets, reflecting their diverse and disparate characteristics, the domestic nature of their growth drivers, and low inter-market correlations. One possible conclusion is to remind ourselves of the importance of maintaining a globally-diversified and liquid portfolio at all times.

A further similarity between Vietnam and other FM and smaller EM markets in general is the disproportionate importance of retail participation in the domestic stock market. In Vietnam’s case, retail activity represents around 95% of daily trade volumes compared to approximately 7% in the US. This phenomenon, together with the absence of captive pools of institutional liquidity, means the market can temporarily be driven by sentiment and momentum, and less so by fundamental value. This can exacerbate market tops and bottoms, and provide longer-term fundamental investors with significant scope for alpha generation. Security selection, though, remains critical given the anticipated differences in the health of corporate operating environments.

1. Source: Dragon Capital, November 2022.