Credit Suisse was acquired by UBS over the weekend, but there was little market respite as the deal exposed possible capital structure vulnerabilities within the global banking system. The European Central Bank tried to strike a balance between inflation and financial stability, a question also being asked of the US Federal Reserve, where small banks remained exposed to deposit runs. Against that backdrop, several Emerging Markets countries have much more balanced monetary policies and banking systems. With inflation well under control Indonesia kept its policy rates on hold, while elsewhere in Asia policy is already easing China cut reserve requirement ratios and Vietnam eased liquidity conditions.

Global Macro

The big news of the weekend was the acquisition of Credit Suisse by UBS for USD 3.25bn, or about CHF 0.76 per share, in an all-share deal. The Swiss National Bank increased its emergency credit line for the combined institutions to CHF 100bn (c. USD 108bn) after forcing UBS to remove a clause where the buyer would be able to cancel the transaction should UBS credit default swaps (CDS) widen by more than 100 basis points (bps).1 UBS five-year CDS widened from 63.5bps to 120bps last week and traded as high as 220bps this morning before declining to 165bps at the time of writing. The uncertainties associated with this new capital instrument add a layer of complexity and financial market contagion, explaining the poor price action post-bailout.

The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) determined that the contingent convertible (CoCo) Additional Tier 1 (AT1) bonds would not be repaid (bailed-in), effectively providing USD 17bn of liability reduction to the new institution, equivalent to one-third of Credit Suisse’s Tier 1 capital.2 The rules determining bail-in triggers varies from country to country. European Banking Authority (EBA) guidelines determine that AT1 bonds would be bailed-in should the institution’s capital decline below 5% of its risk-weighted assets (RWA).

However, the prospect of the Credit Suisse 9.75% PERP (callable in June 2027) seems to give significantly higher flexibility for FINRA to decide on the bail-in event.3 The decision can generate controversy and is a blow to a EUR 250bn AT1 European bond market, which became popular due to its high yield, while the ECB kept policy rates at negative levels for a long period. The Credit Suisse 9.75% PERP (callable in June 2027) traded at 85c on 10 March, 30c last Friday and was quoted at 0.5c–5c this morning on Bloomberg.

Last week, the ECB hiked policy rates by 50bps as pre-committed, but tried to thread a fine needle, saying there were different tools to deal with inflation and financial stability concerns. The reality is that the confidence shock from a run on bank deposits will in itself lead to significantly tighter financial conditions. This is because all banks are tightening lending standards and increasing lending rates regardless of much-discussed 25-50bps trade-offs in what has become largely ceremonial and public relations-like meetings since the poorly-thought-through advent of forward guidance.

US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s testimony to Congress last week was arguably a more important affair, as the banking crisis so far is confined within the US and Switzerland. Yellen was under pressure to agree on a nationwide deposit guarantee to stop the “ongoing” run on small and regional banks, but held her ground, saying that government-funded guarantees on non-systemically important institutions are one-off decisions requiring a supermajority of a committee formed by the US Treasury, the Fed and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The run on regional banks is illustrated by the USD 300bn expansion on the Fed’s balance sheet last week, as banks ignored any stigma from borrowing from the Fed and tapped liquidity primarily via the Fed’s legacy discount windows, as presumably institutions are still learning how to operationalise the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP).

Therefore, US policymakers are stuck between a rock and a hard place. They either guarantee deposits across small regional banks, creating a large contingent liability for the US Treasury (ultimately a liability for taxpayers) or they see market forces (depositors flying, equity holders selling stocks, etc) reducing their exposure to small banks, creating a self-fulfilling liquidity crisis. As we highlighted last week, the challenge with the guarantee is that some large parts of small bank assets, particularly commercial real estate, will come under increased pressure, particularly if interest rates remain elevated. In our view, it renders the willingness of policymakers to both keep rates high to control inflation and provide liquidity to the system to backstop financial stability risks untenable.

The view is also shared by large US banks. Last week, JP Morgan tried to shed some light on the economic impact: “If this credit contraction channel halts small bank loan growth—which was recently increasing over USD 500bn a year – without large banks picking up the slack, we could see 0.5-1.0% shaved off of realized GDP over about a year”. The JP Morgan numbers probably do not consider “reflexivity” effects from a run on small banks. Small banks are the main lenders to small local companies, which will be worried about their ability to borrow from, deposit cash into, and transact with their banks, leading to more depressed sentiment (fear). Small companies are responsible for approximately two-thirds of the jobs created in the US. And as we highlighted last week, small banks have a large share of commercial real estate loans as a percentage of their assets (c. 30%) but also represent around 80% of all commercial real estate loans against a backdrop where vacancy rates stood at 18.7% in Q4 2022, according to Bank of America.4

Therefore, it becomes a matter of time, in our view, for the US authorities to be forced to guarantee depositors. That would only be possible, in political terms, with a significantly tighter regulatory environment which would stifle the ability of these banks to provide their services. The alternative would be a temporary guarantee on deposits, perhaps matching the 12-months on the Fed’s BTFP facility, allowing banks to de-risk their balance sheet and giving them confidence to rebuild. That could provide a short term backstop, allowing for a stronger rebound in market sentiment. However, if rates remain elevated and commercial real estate suffers a series of credit events during the guarantee period, then the US Treasury would be exposed not only to liquidity risks, but having to backstop deposits from insolvent institutions.

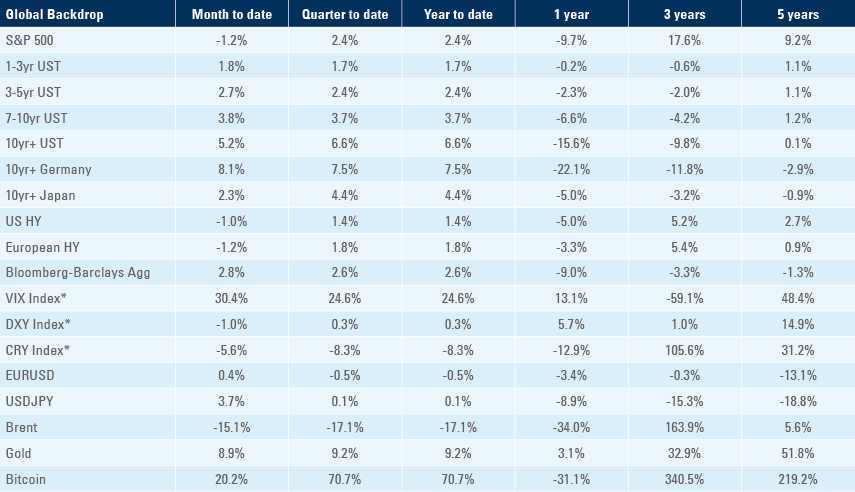

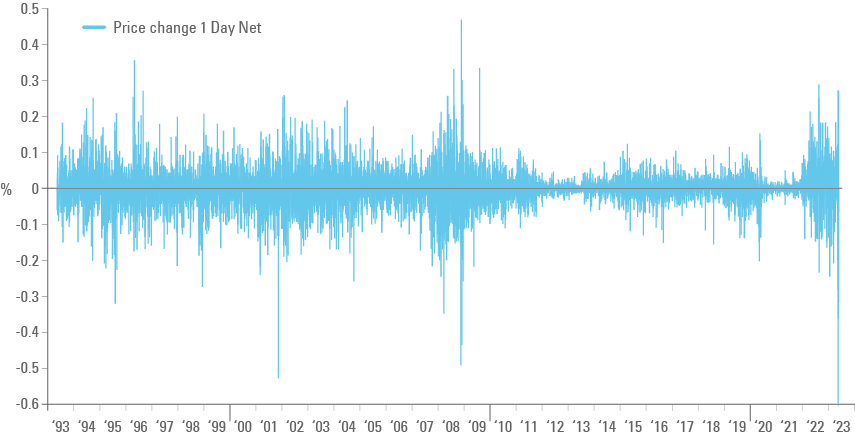

In global macro terms, if the events described play out, there would be a significant increase in fiscal expenditure in the US, bringing the potential for a steeper US Treasury curve and a much weaker US dollar. It is hard to make the case that the USD will have any support, as to backstop the crisis the Fed would have to acknowledge there is no way to differentiate between inflation fighting and financial stability, thereby cutting rates to a level where banks assets are whole and sound and allowing for confidence to be restored. Highlighting the challenging environment, depth of trading the entire US Treasury curve declined last week to similar levels experienced during the 2008 great financial crisis and the 2020 Covid-19 crisis. This is explained by the massive increase in volatility of US Treasury instruments as two-year government bond intraday range increased from 0.39% to 0.69% last week, leading to a net price change of -0.6% last Monday, larger than the two previous records over the last 30 years (-0.53% on 13 September 2001 and -0.44% on 15 September 2008) as per Figure 1.

Is there a path where none of these events happen? Where confidence in the system is restored and the economy doesn’t have to endure a recession? There certainly are a few paths, but they are narrowing faster than expected and the solutions will involve politically challenging trade-offs such as moral hazard versus systemic risks and inflation versus financial stability.

Fig 1: Generic two-year US Treasury

Emerging Markets

Indonesia: The trade surplus surged to USD 5.5bn in February from USD 3.9bn in January, more than USD 2bn above consensus expectations as exports rose by 4.5% year-on-year (yoy). Imports fell 4.3% yoy, driven by a decline in the imports of raw materials. Bank Indonesia kept its policy rate unchanged at 5.75%, in line with consensus. Rates are likely to remain unchanged for a while (unless there is a significant change in the global macro environment) as Indonesian policymakers managed to do what very few central banks have achieved in recent years – they contained inflation and inflation expectations with a moderate hiking cycle (+225bps), thanks to good coordination between fiscal and monetary policy, thereby ensuing no large imbalances as experienced in Developed Market (DM) economies. As a result, consumer price index (CPI) inflation declined from a yoy rate of 6.0% in September 2022 to 5.5% in February 2023, while core CPI peaked at 3.4% and declined to 3.1% yoy over the same period.

Vietnam: The State Bank of Vietnam cut the policy rates at which it lends to banks to support economic growth as inflation slowed by 60bps to 4.3% in February. It cut the overnight lending rate in the inter-bank market by 100bps to 6.0%, its discount rate by 100bps to 3.5%, and the cap on short-term loans in some sectors by 50bps to 5.0%, but it kept the benchmark refinancing rate unchanged at 6.0%.

China: Industrial production and retail sales were as expected at 2.4% yoy and 3.5% yoy respectively, but fixed asset investments were 100bps ahead of consensus at 5.5% yoy, driven by residential property sales which increased by 3.5% yoy in the cumulative January-February 2023 period. The People’s Bank of China kept its one-year medium-term lending facility policy rate unchanged at 2.75% but lowered the reserve requirement for banks by 25pbs to 10.75%. Li Qiang and his team took over the Premier position responsible for the economy from Li Keqiang and hosted his first press conference. He gave a pro-business, pragmatic speech that highlighted the importance of the private economy and committed to reform and opening the economy.

Argentina: CPI inflation rose to 6.6% month-on-month (mom) in February, up from 6.0% mom in January, lifting the yoy rate by 370bps to 102.5%, breaking the 100% psychological milestone. Argentina’s high inflation is a result of years of fiscal deficits funded by monetary expansion, which, despite capital controls, has led to a depreciating currency and much higher prices than the official foreign exchange (FX) regime suggests because of the black market. The situation worsened recently as a severe drought impaired the country’s crops.

Snippets

- Brazil: The national unemployment rate rose by 50bps to 8.4% in January, 20bps above consensus. Nevertheless, this was the lowest level for the month of January in seven years. Consensus expectations for CPI inflation were unchanged for 2023 at 5.3%, but increased by 20bps to 4.2% in 2024.

- Colombia: Retail sales rose 1.2% yoy in January, 300bps ahead of expectations, after declining 1.8% in December. The survey for economic activity jumped 460bps to 5.9% yoy over the same period. The trade deficit increased from USD 935m in December to USD 1.48bn in January, in line with consensus.

- India: The yoy rate of CPI inflation declined by 10bps to 6.4% in February, in line with consensus, as the wholesale price index (WPI) dropped by 80bps to 3.9% over the same period. India’s trade deficit narrowed from USD 17.8bn in January to USD 17.4bn in February, almost US 2bn better than consensus.

- Malaysia: The yoy rate of industrial production declined by 100bps to 1.8% in January in, 50bps below consensus.

- Mexico: Industrial production declined by 20bps to 2.8% yoy in January, 40bps above consensus. Manufacturing production rose 210bps to 4.8% yoy over the same period.

- Nigeria: The yoy rate of CPI inflation rose by 10bps to 21.9% in February, in line with consensus.

- Peru: Lima’s unemployment rate declined by 130bps to 7.3% in February. Peruvian fiscal accounts and economic activity continued to outperform despite endless political noise from impeachment attempts of presidents across all parties.

- Philippines: The trade deficit widened from USD 4.5bn in December to USD 5.7bn in January as exports dropped by a yoy rate of 13.5% at USD 5.2bn. Meanwhile, imports rose 3.9% yoy to USD 11.0bn in January. Overseas cash inflows slowed to USD 2.8bn in January from USD 3.2bn in December, in line with consensus.

- Poland: CPI inflation declined from 2.5% mom in January to 1.2% mom in February, but the yoy rate rose by 180bps to 18.4% due to base effects. Core CPI inflation rose from 0.9% to 1.3% mom and the yoy rate increased by 30bps to 12.0% over the same period. The current account moved from a USD 2.5bn deficit to a USD 1.4bn surplus in January, and the trade balance moved from a USD 2.7bn deficit to a USD 1.2bn surplus, both significantly better than consensus.

- Romania: CPI inflation rose from 0.3% in January to 1.0% mom in February as the yoy rate widened by 40bps to 15.5%. Wage inflation increased by 160bps to 15.0% yoy in January. The trade deficit declined to USD 2.3bn in January from USD 3.1bn in December.

- Saudi Arabia: The yoy rate of CPI inflation declined 40bps to 3.0% in February.

- South Africa: Gold production rose by a yoy rate of 3.7% in January after declining 3.3% yoy in December, as overall mining production contracted 1.9% in yoy terms in January. Manufacturing production rose from 0.5% mom in December to 1.1% mom in January, as the yoy rate improved from -4.5% yoy to -3.7% yoy. Retail sales also rose from -0.5% mom in December to 1.5% mom in January, but the yoy rate was down 30bps to -0.8%.

- South Korea: The unemployment rate fell 30bps to 2.6% in February, 40bps better than consensus.

- Thailand: The current account deficit widened from USD 5.9bn in December to USD 9.9bn in January, in line with consensus. House prices rose by 6.9% mom in January or 153.1% yoy after 5.3% in December.

Developed Markets

United States: Inflation continued to decline, particularly producer price inflation (PPI). Manufacturing and consumer surveys declined in March, but the job market remained strong. CPI inflation rose by 0.4% mom in February, down 10bps from January as the yoy rate declined by 40bps to 6.0% as CPI ex-food and energy declined 10bps to 5.5% yoy, both in line with expectations. PPI showed 0.1% mom deflation in February after 0.3% mom in January as the yoy rate declined 110bps to 4.6%. PPI ex-food and energy was unchanged in February after 0.1% mom in January, as the yoy rate declined 160bps to 4.4% over the same period, both significantly lower than consensus. Economic survey results were weak. The Empire Manufacturing dropped from -5.8 in February to -24.6 in March, the Philadelphia Fed was unchanged at -23.2 and University of Michigan consumer sentiment declined from 67.0 to 63.4 as current conditions dropped 4.3 to 66.4 and expectations declined 3.2 to 61.5. The one-year inflation expectation declined 30bps to 3.8% in March, but 5-10 years dropped 10bps to 2.8%. However, jobless claims declined by 20k to 192k in the week of 11 March, while continuing claims declined by 1.68 million from 1.71 million in the prior week. S&P Global ratings kept its AA+ sovereign rating unchanged and the outlook stable.

Europe: The ECB hiked its policy rates by 50bps, with deposit, refinancing and lending facilities reaching 3.0%, 3.5% and 3.75% respectively. This was in line with the pre-commitment by President Christine Lagarde in the previous meetings. During the press conference, Lagarde pledging to keep fighting inflation while showing the financial community that the ECB cared about financial stability, suggesting both objectives are compatible. On the positive side, Lagarde scrapped forward guidance, saying several times that economic data and financial market developments will guide its next policy decisions. Market reaction was muted because the technical positioning on the EUR was light, and the epicentre of the problems are in US regional banks and Switzerland.

1. CDS is a contract designed to provide protection against credit events. The seller of protection receives a premium (expressed in basis points). In the event of default, the seller has the obligation to pay the buyer of CDS the full notional of the swap upon receiving defaulted debt instruments (or cash settlement by the difference between the notional versus the value of the defaulted debt) determined by the calculation agent. See – https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/creditdefaultswap.asp

2. See https://www.ft.com/content/d1ae9a54-c4a7-4742-8b2d-afff549f4f95

3. From the Credit Suisse 9.75% PERP prospectus: “FINMA has the power to open restructuring proceedings with respect to [Credit Suisse Group (CSG)] under Swiss banking laws (see “– CSG is subject to the resolution regime under Swiss banking laws and regulations” below), and, if the Notes have not already been subject to a Write-down, could convert the Notes into equity or cancel the Notes, in each case, in whole or in part. Holders should be aware that, in the case of any such conversion into equity, FINMA would follow the order of priority set out under Swiss banking laws, which means, among other things, that the Notes would have to be converted prior to the conversion of any of CSG’s subordinated debt that does not qualify as regulatory capital with a contractual write-down or conversion feature. Furthermore, in the case of any such cancellation, FINMA may not be required to follow any order of priority, which means, among other things, that the Notes could be cancelled in whole or in part prior to the cancellation of any or all of CSG’s equity capital.”

4. See ‘This time was not different: the Fed hiked until something broke’, Weekly Investor Research, 13 March 2023.

https://rsch.baml.com/report?q=SeBpaAFrvi967gkCZCNadg&e=mike.lekan%40bofa.com&h=l3Ml2g and https://markets.jpmorgan.com/research/email/-tbqfr96/VB0oV4nBiRCw6FWL4ecVGA/GPS-4363927-0

Benchmark performance