The pivotal role of forest preservation in the battle against climate change is well understood. Forests provide a crucial carbon sink, the destruction of which will further accelerate global warming. Indeed, an estimated 15% of global carbon emissions can be attributed to deforestation1, second only to the burning of fossil fuels.

The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) was marked by an ambitious statement signed by over 100 countries to halt and reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2030. The following year, the UN’s 15th Convention on Biodiversity (COP15) saw the adoption of the historic ‘30x30’ global target, which aims to protect at least 30% of the world’s land and ocean by 2030. Yet, despite these pledges, deforestation rates remain high. Tragically, the vast majority occurs in the tropical rainforests of the developing world; biomes that harbour over 50% of the Earth's biodiversity.

While Developed Markets (DM) can somewhat offset the impact of resource depletion through imports, Emerging Markets (EM) are more reliant on their natural resources. Put simply, deforestation is fundamentally unsustainable – environmentally, socially, and economically. As a result, particularly within EM, exposure to the practice brings huge risks to local communities, businesses, and economies. As investors, it is essential both to understand these risks and to work to manage them.

A complex challenge…

The reversal of deforestation in tropical regions is an undeniably bifurcated issue. Today, 1.6 billion people rely on forests' resources for their livelihoods.2 In Latin America and Southeast Asia, forests are cleared to grow crops, dig mines, and create space for cattle. In Africa, trees are cut largely for subsistence agriculture and fuelwood, which remains a primary energy source for many communities. Therefore, when it comes to tackling deforestation, conflicts of interest exist from the individual to the federal level. Indeed, one-third of deforestation is still effectively legal.3

Against this backdrop, it is important to recognise that demand drives supply. Deforestation-linked commodities are distributed and consumed internationally. Brazil is the world's largest beef exporter, meeting around 25% of global demand. Brazil and Indonesia are also by far the world's biggest soybean and palm oil exporters, commodities that have both contributed to the destruction of vast swathes of tropical rainforest.

Consequently, reversing deforestation requires multinational policy cooperation along value chains. In 2023, the European Union (EU) introduced its 'Regulation on Deforestation-free products', which sets out a blueprint for how deforestation can be managed, not just by the source countries, but by the regions driving end demand. Between 1990-2008, EU imports made up 36% of deforestation-linked crop products and 25% of deforestation-linked animal products. However, the implementation of this regulation requires operators wishing to place key commodities (and their derivatives)4 on the EU market to prove that their production has not contributed to deforestation. The impact is likely to be powerful and provide a strong incentive for producers to increase the productivity, rather than the scale of their operations.

However, tracing complex supply chains will, in many cases, be both difficult and expensive. To what extent exporters will simply seek to redirect their exports to jurisdictions with lower barriers remains to be seen. An estimated 16 million people in Indonesia work in the palm oil industry, for example, while 9% of Brazilians work in agriculture. Therefore, Just Transition principles5 must be considered when expecting to stop expansion these key industries in forested areas, which still make up most of both countries’ land masses.

…particularly for Emerging Markets

Almost half of all deforestation takes place in Brazil and Indonesia, with 95% of deforestation today taking place in the tropics. Therefore, this is a particularly relevant issue for stakeholders in these regions. Along the equator, deforestation rates tend to be linked to each country's stage of economic development. Brazil, for example, went through a period of very rapid deforestation in the 1980s and 1990s, and while the practice remains widespread, the rate of destruction has since slowed. Indeed, a large part of Brazil’s increase in beef production in the 21st century was due to higher productivity, rather than increasing pasture area. Indonesia’s deforestation rate remains a concern, but it has, in fact, also declined quite sharply since 2015.However, countries such as Myanmar, Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo are in an earlier stage of economic development, and thus are losing forests increasingly quickly. In the coming decades, it is in these fast-growing economies where we expect to see the most rapid loss of primary forest (forest that has never been cleared before), unless preventative action is taken.6

Financing a solution

The variety of drivers and circumstances around deforestation demand a multifaceted approach to solutions. Strict enforcement of punitive measures is important, but in less-developed nations, policymakers increasingly recognise the impact of incentive-based approaches to forest management. Understanding the perspective of local communities is crucial. Therefore, to sustainably stop deforestation in low-income rural areas, forest preservation must facilitate economic growth, rather than hinder it. However, aligning sustainable forestry with economic development can be undeniably challenging at a local level, given the more immediate benefits of logging for timber and agriculture.

In this context, cash incentives can serve as a bridge towards reaping the longer-term rewards of sustainable development. As the preservation of forests is vital not only for the countries where they are situated but for the world climate, wealthier nations have both a reason and a responsibility to shoulder a significant portion of the financial burden in addressing this issue, in our view. The Energy Transitions Commission estimates it could cost between USD 150-300bn a year to incentivise and implement sustainable forest management at a sufficient scale to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030. Yet international finance for forests currently averages only USD 2.2bn per year.7 For perspective, global government spending on fossil fuel subsidies reached USD 7.0trn in 2022.

Filling this financing gap will be more difficult while scepticism exists around current incentive-based systems. The largest of these is the UN-sanctioned REDD+, launched in 2007.8 Under this framework, results-based payments, financed primarily by contributions from governments, are exchanged for verified emission reductions related to sustainable forestry. However, just USD 2.9bn has been approved for REDD+ activities since its inception. For an initiative enshrined in the 2015 Paris Agreement – and with an international scope (57 countries have received money so far) – this suggests both parsimony on the part of wealthier nations and a lack of belief in the programme. Part of the problem may be a lack of clarity around the ownership of emission reductions. Laws around REDD+ credits vary between countries. In many cases, they can become an intangible asset traded between third parties, including governments, to achieve mitigation targets and receive financing. This can cause frictions, and ultimately impede the stakeholders who work hardest on forestry from benefitting most from the scheme. This can undermine the framework's impact and make it more likely that trees which are not cut down now would be cut down later.

Costa Rica's Payments for Environmental Services Program (PES) offers a useful case study of a successful incentive system, with money going directly to the landowners and communities who preserve woodland. Between 1997 and 2005, the Costa Rican government spent approximately USD 110m on PES contracts. During this period, forest cover grew from 42% (of the country) to 51%. However, due to the idiosyncratic nature of EM economies when it comes to deforestation, there is unfortunately no panacea. Thoughtful and creative solutions will be necessary to replicate Costa Rica’s success in other countries, whether through more effective implementation of REDD+ or otherwise.

Deforestation and portfolio risk

For investors, reducing exposure to deforestation is an important consideration from both a social responsibility and a portfolio risk perspective. Like other unsustainable business practices, continued deforestation presents various threats to asset prices. These can manifest through issuer-specific regulatory and reputational risks, which can lead to more expensive financing, or stranded assets and potentially loss of market access. As international regulation over deforestation tightens, these risks rise.

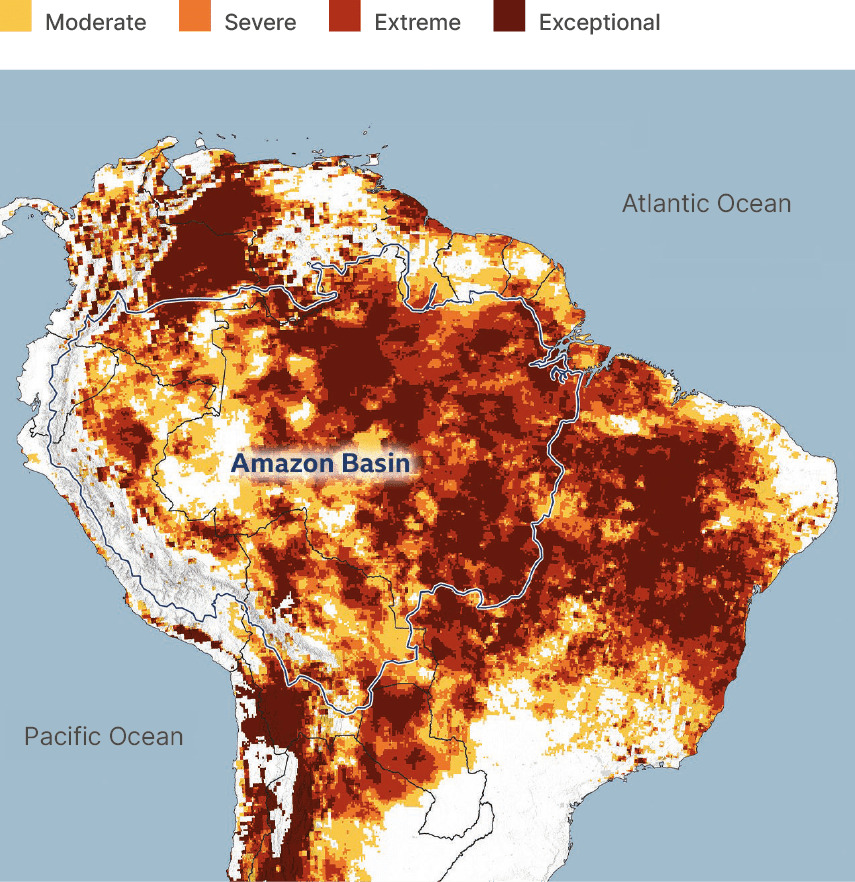

However, there is also a growing awareness among investors of the systemic risk that deforestation brings to the future earnings of many companies. Unchecked, deforestation will undermine productivity across sectors that depend either directly or indirectly on natural inputs. For example, the effects of large-scale deforestation raise the likelihood of lower agricultural revenues due to droughts, or loss of productive land due to flooding and landslides. The approach of a climatic tipping point (where enough trees are felled to permanently alter the regional climate) dramatically increases these risks. Without the forest, evapotranspiration decreases, which means there is less moisture in the atmosphere for rain. This leads to less cloud cover, warmer temperatures and longer dry seasons. Unfortunately, this phenomenon is already materialising; between June and November 2023, the Amazon recorded its worst drought on record, amidst a delayed monsoon.

Naturally, these kinds of extreme weather events will have a consequential macroeconomic impact for sovereigns. A report shared by the World Bank estimates that continued deforestation in the Amazon will put at risk up to USD 317bn of value per year9, which is more than seven times the estimated annual private exploitation value of deforestation-linked agriculture, timber, or mining in the region.

As nature continues to deteriorate, businesses are progressively more at risk from not only growing reputational and legal risk, but operational and financial, as direct inputs disappear and the ecosystem services, on which businesses depend, stop functioning.

The creation and enforcement of robust government policies will be a vital component in reducing deforestation rates. Equally, multilaterally pooled public finance, if allocated effectively, can provide powerful incentives. However, private companies also have a role to play alongside governments in aligning business and supply chain activities with the preservation of the natural world. In its ability to both selectively allocate capital and engage with corporate and sovereign issuers; we believe the financial sector can be an important positive catalyst here.

Engagement - Corporate issuers

As either shareholders or creditors, asset managers can exert significant influence on corporate issuers to operate more sustainably and thus contribute to reducing both their environmental impact and risk. For investors to measure and track this risk, frequent and high-quality company reporting is necessary. While sustainability disclosure is improving quickly globally, good data on deforestation exposure is still scarce. When available, it is often from third-party data providers which have limited visibility into companies’ supply chains. The publication of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) framework in 2023 helped set a benchmark for nature-related reporting requirements that companies can work towards achieving. Adoption of the framework becomes even more relevant for companies doing business in the EU, where a lack of investment into supply chain traceability may soon leave exporters in a challenging position in the face of impending regulation on deforestation-free products.

Consequently, pushing companies to align their disclosure with internationally accepted standards is often a primary engagement objective for active asset managers. Industry leaders will set an example (positive or negative). While only a minority of global beef and soy exporters disclosed on deforestation in 2022, those that did included Brazil's three biggest soy farmers, as well as its largest meatpackers. As part of our environmental, social and governance (ESG) engagement strategy and focus on deforestation, Ashmore is in the process of engaging with some of Brazil’s largest agricultural companies. Encouraging these corporates to monitor and reduce their negative impact on forests is important not only for the environment, but also to limit credit risk in corporate debt investments and increase access to a wider array of capital for the issuers. On the equity side, reputational and regulatory risk around deforestation can be reflected in stock prices. When this risk turns into controversy, it can cause severe downside and volatility. Investors are already sensitive to these dynamics, reflected in the premium of sustainability-linked bonds to traditional bonds.

To align our engagement efforts with other industry leaders, Ashmore joined the SPRING Initiative in April 2024. SPRING is a Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) stewardship initiative for nature, convening investors to use their influence to support halting and reversing global biodiversity loss by 2030. Focusing on engaging with corporates on deforestation, SPRING has put together a focus list of 40 companies whose environmental strategies are influential within their regions. As of March 2024, the initiative was endorsed by 159 investors managing USD 10.3trn in assets under management (AUM).

Sovereign engagement

After a steady decline for several years, deforestation rates in Brazil soared to a 15-year high in 2021, during the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro, a well-known climate change sceptic. In his tenure, environmental law enforcement was weakened and defunded. However, when Luiz Lula da Silva took office in January 2023, Brazil's deforestation rates recorded a 35% reduction within six months. Government signalling is powerful, and the perception that presidents care about deforestation matters.

The influence that financial institutions can have on government policy can seem less obvious than with public companies. Local banks’ exposure and impact will be the largest of all due to the financial risks that deforestation poses to the economies in which they are based. Large domestic financial institutions are the most powerful conduit of capitalist systems and, therefore, often have a direct relationship with governments. However, global asset managers who invest in EM sovereign debt face a similar – albeit more diversified and unlevered in nature – exposure to deforestation. While most will lack the leverage of the largest global and local banks, they should also use their influence to protect their clients’ interests and seek to make a positive impact.

To appeal to governments, foreign investors’ collaboration and multilateral engagement can be impactful. In 2020, the Investor Policy Dialogue on Deforestation (IPDD) was launched with the goal of coordinating a public policy dialogue between the global asset management industry and government policymakers. The IPDD "seeks to ensure long-term financial sustainability of investments […] by promoting sustainable land use and forest management." As of October 2023, IPDD was supported by 81 financial institutions from 21 countries, representing around USD 10.5trn in AUM. In Brazil, for example, the group worked towards a sustained reduction in deforestation rates, enforcement of Brazil's Forest Code, and public access to data on deforestation and commodity supply chains.

Since 2020, the IPDD has also broadened its scope to policymakers in Indonesia, where an impending change of government brings new risks to environmental policy continuity. Part of the appeal of collective sovereign investor engagement is its ability to promote positive policy momentum through political cycles. Recognising this potential, Ashmore became a signatory to the IPDD in early 2024.

Our objective

As a dedicated EM investor with a local presence in countries profoundly affected by deforestation, including Indonesia, Peru, and Colombia, this is a particularly pertinent issue to our business. From an investment perspective, we recognise the preservation of natural ecosystems, particularly forests, is paramount for the long-term success of these, and many other EM economies.

Therefore, Ashmore is committed to active engagement with both our corporate and sovereign investees on deforestation. By leveraging long-standing issuer relationships and collective investor engagement vehicles, we aim to advocate for practices that prioritise the protection and restoration of forests. Through monthly meetings of our Deforestation Engagement Committee, which includes our Head of ESG, Risk and members of the Investment Committee, we will continuously monitor the progress of ongoing engagements, as well as the exposure of our portfolios to deforestation-related risk. As with our broader ESG strategy, our deforestation engagement initiative is underpinned by our fundamental interest in the sustainable development and resilience of the countries in which we invest.

1. See – https://iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/forests-and-climate-change

2. See – https://www.wwf.org.uk/learn/landscapes/forests/pathways-report-summary

3. See – https://globalcanopy.org/insights/videos-and-podcasts/what-makes-an-effective-law-to-stop-commodity-driven-deforestation

4. The regulation affects seven specific commodities (cocoa, coffee, soy, palm oil, wood, rubber, and cattle) and their derivatives, as well as products made using these commodities (e.g., leather, cosmetics, chocolate, etc.).

5. “Just Transition” is a principle, a process and a practice. The principle of just transition is that a healthy economy and a clean environment can and should co-exist. The process for achieving this vision should be a fair one that should not cost workers or community residents their health, environment, jobs, or economic assets.

6. See – https://ourworldindata.org/deforestation

7. See – https://www.energy-transitions.org/financing-the-transition-the-costs-of-avoiding-deforestation

8. REDD: Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (with the + referring to other activities that promote sustainable forestry).

9. See – https://news.mongabay.com/2023/05/world-bank-brazil-faces-317-billion-in-annual-losses-to-amazon-deforestation

10. See – 17 World Economic Forum. (2020) Nature Risk Rising. See https://www.weforum.org/publications/new-nature-economy-report-series/