Brazil’s vast natural resources have helped build a resilient economy, backed by a sophisticated financial system and a well-educated, hyperconnected population. However, persistent political volatility and inefficient public spending have hindered progress.

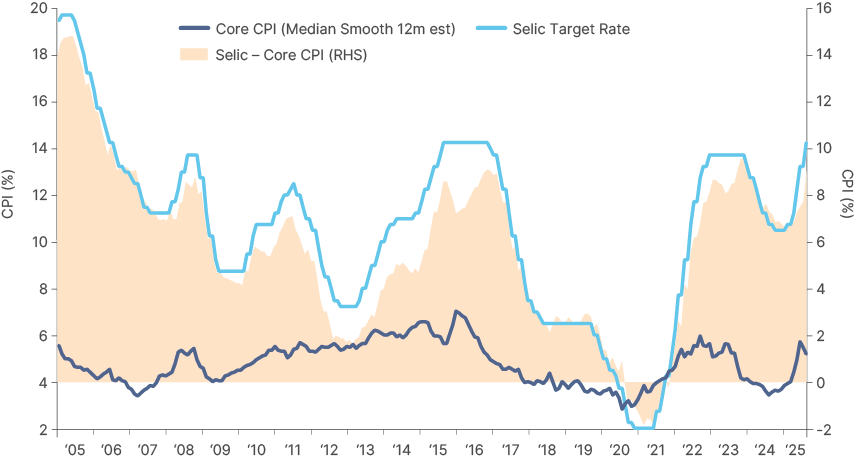

Post-Covid fiscal profligacy bolstered growth but has driven the budget deficit to nearly 8.5% of gross domestic product (GDP), with soaring interest costs. This dynamic has de-anchored inflation expectations and led to the central bank hiking the Selic rate back up to 14.25%. Investor confidence in Brazil is now very low.

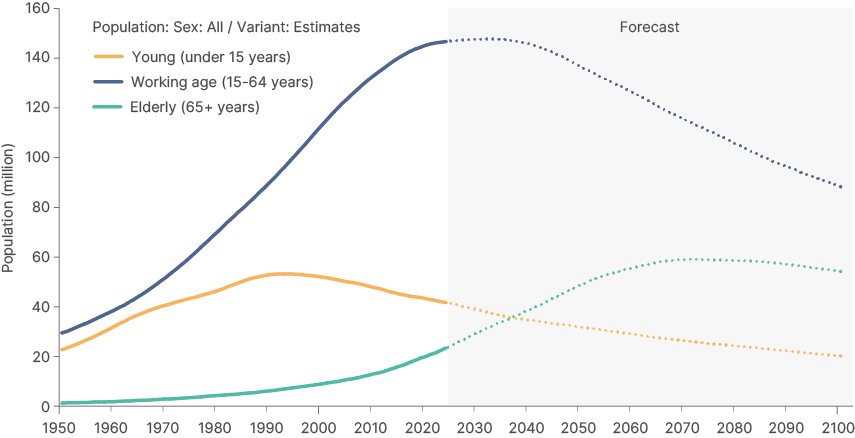

However, with cheap valuations comes opportunity. The upcoming political cycle suggests a potential shift towards a more market-friendly and technocratic leadership, which could pave the way for fiscal consolidation and productivity-enhancing investment. But with Brazil’s demographic dividend fading, the ‘land of the future’ cannot afford to wait much longer.

Context

It has always been easy to see Brazil’s potential. More than twice the size of India, Brazil is an energy, mining and farming powerhouse. Stefan Zweig named it the ‘land of the future’ in a vivid 1941 book, and the nickname stuck. But over 80 years later, the axiom has developed more than a hint of irony. Certainly, Brazil today is a relatively well-developed and sustainable economy. Its energy mix is now 88% clean, due to its large hydropower capacity. It is the seventh-largest oil producer in the world, and supplies 20% of the world’s iron ore, second only to Australia. Brazil’s vast, fertile landmass supports its position as the world’s number one exporter of soybeans, sugar, chicken meat, beef, coffee, and even orange juice. It has a hyperconnected population, a well-educated middle class and a strong, sophisticated financial system, with private sector credit reaching 72% of GDP in 2024, and continuing to grow quickly. This makes Brazil competitive in the financial and tech sectors, with various strong companies such as NuBank emerging in recent years.

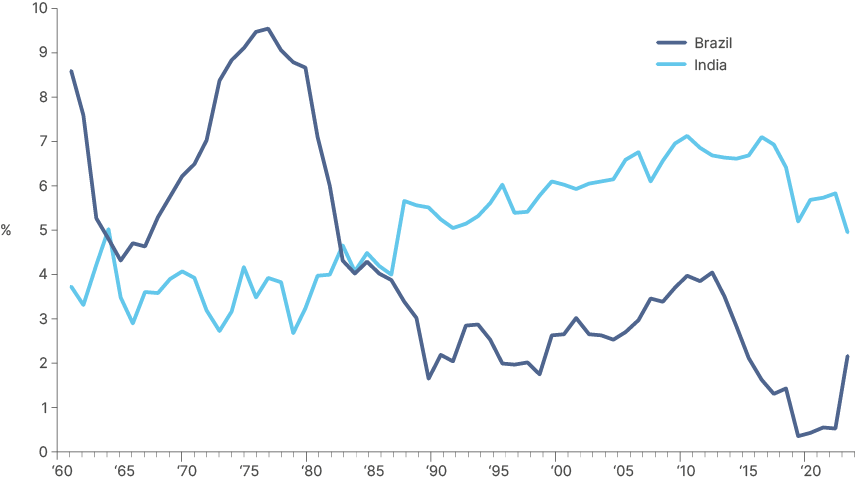

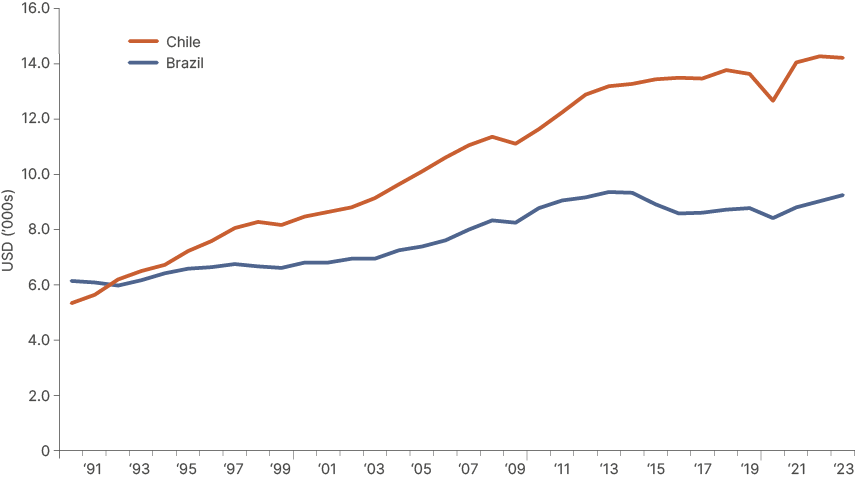

But despite all its assets – and inherent magic that so captivated Zweig and many travellers before and after – the ‘land of the future’ has consistently struggled to fulfil its potential. Over the years, volatile politics and incoherent economic regimes have weighed on progress, leading to slower GDP per capita growth than regional peers like Chile. With GDP per capita just 10% higher in USD purchasing power parity (PPP) terms since the Global Financial Crisis, Brazil is stuck in the ‘middle-income trap’.

Fig 1: GDP per capita USD: 2015 price

Currently, investor confidence in Brazil is very low, with asset prices trading at depressed levels that should prick contrarians’ ears. Brazil is a resilient economy, and betting on its downfall has historically been a mistake. Fortunately, there is a relatively clear path forward towards more stable prosperity. Brazil must consolidate its fiscal deficit and improve the quality of its expenditure by boosting capex. While politically difficult, balancing the budget has been done before, and can be done again. However, with the working-age population set to peak in 10 years, its demographic dividend will soon fade. ‘The land of the future’ needs to act now.

Fig 2: Brazilian demographic forecast

The next section discusses Brazil’s recent problems. For a more comprehensive historical overview, please see Appendix 1.

Stumbling on fiscal problems

Last year, Brazil’s real GDP growth was 3.4%, the strongest since 2011 apart from the postpandemic recovery. Unemployment has fallen from 13% pre-Covid down to 6.2% in 2024, the lowest since 2015. However, while the strong average growth since 2019 is founded on economic reforms of previous regimes, the increased social security support under President Luis Ignacio Lula da Silva’s centre-left government has played a significant role. It has also led to a widening of fiscal deficits and de-anchoring of inflation expectations.

The exceptional circumstances of Covid allowed Brazil, under former president Jair Bolsonaro, to break its fiscal rules through a ‘State of Emergency.’ In 2020, Brazil’s deficit rose to 7.3% of GDP. The next two years also saw excessive spending that only met fiscal rules through one-off revenue measures and quasi-creative accounting.

In 2023, a new fiscal framework was established as Lula began his third term. Expenditures were capped at 70% of primary revenue growth in the 12 months ending in June of the previous year. This differed from the previous rule, which capped spending growth to trailing inflation, regardless of growth. The problem with this fiscal rule, like others before it, is it is inherently pro-cyclical. As revenues grow when GDP expands quickly, so does spending and often inefficiently. Moreover, when revenues slow in a recessionary environment, expenditure growth is limited, thus exacerbating the downturn. To reduce the pro-cyclicality, spending growth under the new rule has a floor of 0.6% and a cap of inflation +2.5%.

Alas, the initial commitment to fiscal responsibility has been repeatedly undermined. The primary surplus was originally targeted at 0.5% in 2024/25 and a 1.0% surplus in 2025/26, but these were changed to 0% and 0.25%, respectively. The revised target was met for the 2024 fiscal year largely through one-off revenue-enhancing measures, rather than fiscal restraint. Furthermore, quasi-fiscal measures – such as payroll-linked credit extensions – made it evident that the government was unwilling to seriously tackle expenditures.

The fiscal profligacy was confirmed by recent proposals, including raising the income tax exemption threshold to BRL 5,000 from 2026, exempting 10 million further taxpayers, and leaving 56% of the country’s workforce free from income tax. The government is looking to offset these losses by taxing the wealthiest 0.1%, but the approval of the measure, and its actual revenue-raising potential, are uncertain.

Current backdrop

A loss of fiscal credibility under Lula has prompted capital flight. The BRL weakened as a result and brought inflation expectations sharply higher, forcing the central bank to hike policy rates sharply to 14.25%, close to 10% in real terms, the second highest across emerging markets.

Fig 3: Selic Rate vs Core CPI

The monetary medicine to the fiscal malaise stabilised the currency but with the side effect of further straining government finances. The cost of servicing debt accounts for most of the 8.5% of GDP budget deficit as Brazil’s net debt-to-GDP ratio stands at 60.8%, and gross debt approaches 76%, among the highest in emerging markets, proving that Brazil urgently needs budgetary reforms.

The tighter monetary policy coinciding with the fading of Lula’s fiscal stimulus, explains why growth is expected to drop to around 2% this year. While Brazil’s trade deficit with the US means it is less exposed to tariffs, the broader effects of slower global growth – driven by Trump’s trade policies – could dampen commodity prices, undermining revenues for Brazil as a major exporter.

Fig 4: GDP Nowcast

The unsustainable fiscal dynamics had investors labelling Brazil ‘un-investable’ by late last year, leading to humiliating valuation levels. But betting on a collapse of the country’s social-economic structure has historically been premature. With fiscal concerns priced in, among the highest real rates in the world, a weak BRL, and equity markets trading near 2008 levels, Brazil offers an enticing value opportunity for investors who can envision a path forward.

2026 elections as the key catalyst

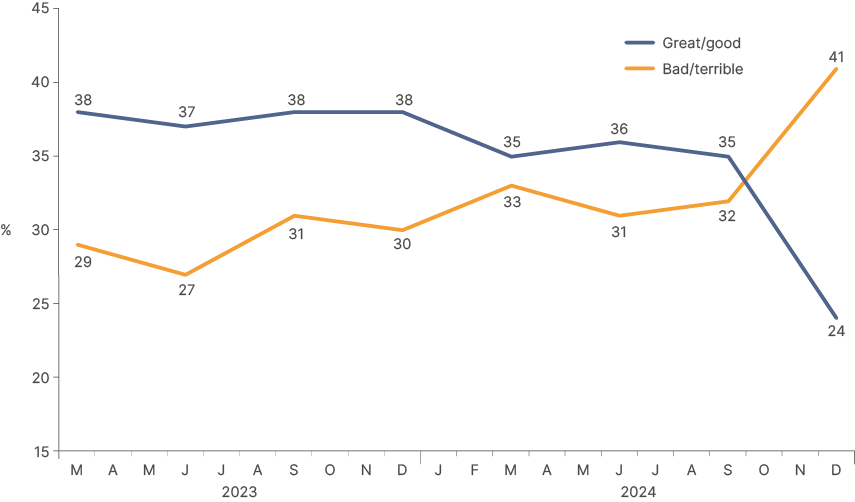

Elections are not until October 2026 but are very much on investors’ radars. Consensus has converged on the conclusion, rightly or wrongly, that it will not be Lula who will restore fiscal credibility in Brazil. Lula’s approval ratings recently dropped to historical lows of between 11% and 30%, depending on the poll.

Fig 5: Presidential approval rates

Voters blame his economic policies for their falling purchasing power, and classic ‘Ricardian equivalence’ has raised fears of future tax hikes. While greater commitment to reducing inflationary government spending could help bring down prices, and thus rates, earlier, it is more likely Lula will spend even more in the run-up to the election to garner support from his political base, many of whom are from a poorer demographic.

Lula’s approval ratings were expected to start stabilising, but last week, his party was hit by a BRL 8bn corruption scheme in the pension plan for public servants. The corruption scheme, which basically involved paying kickbacks to service providers, started in previous governments but increased meaningfully under the current government. Worst, Lula’s own brother – Frei Chico – is under investigation. If Lula himself is seen as directly involved and his popularity drops further, he may lose control of Congress, making it harder for him to get anything approved.

This backdrop mirrors the US, where the Democrats lost to the right-wing Republicans, in part, due to cost-of-living concerns, which had arisen largely because of prolonged pro-cyclical fiscal expansion. The parallel ends there, though. While Donald Trump passed through various court cases and was re-elected, Brazil’s former right-wing President Bolsonaro is ineligible and likely to serve time for his role in plotting a coup to remain in power. Bolsonaro has pledged to wait until March 2026 before announcing his support for an alternative candidate. He has revealed a preference to appoint his wife, Michelle, or one of his sons, but he is also open to working with a centre-right politician. In our view, the latter is more likely. This candidate would probably emerge from a bloc of centre-right Governors, the Governors of Sao Paulo, Guias, Minas Gerais, Rio Grande do Sul, and Parana. All are deemed competent managers with liberal economic policies that would boost market confidence in Brazil. Importantly, they have been in constant dialogue. Their coordination is very important to avoid fragmentation and to open the field for more major reform.

In short, the race will be defined by Lula and Bolsonaro’s actions. Lula’s age and poor performance in polls suggest he should now appoint a successor, but no one from the left can quite match his political gravitas. His two best bets are his Finance Minister Fernando Haddad and his Vice President Geraldo Alckmin, but neither is regarded as stellar by either the party or the public. If Lula does not run, the risk is a more fragmented race, as more members of the opposition would back their chances of winning.

If Lula does run, the incentive is greater for the opposition to group together to back a single candidate. A centre-right governor with the support of Bolsonaro would be very competitive.

Building the country of tomorrow, today

The best-case (and likely) scenario is the opposition rallying around Tarcisio de Freitas, the current governor of Sao Paulo and Bolsonaro’s former Infrastructure Minister. A technocrat and former engineer, Tarcisio has led the completion of several Brazilian infrastructure projects and the privatisation of Eletrobras. He also oversaw the approval of market-friendly legal frameworks for natural gas, railways and cabotage shipping. As the governor of Sao Paulo, he has increased investments from 3% to 15% of the government’s revenues. He only managed to do so by cost cutting, including 20% of personnel, closing and privatising state-owned companies, and revising tax benefits that did not make sense. Well-designed concessions allowed for private capital mobilisation with BRL 350bn of private investments in slightly more than two years, much larger than the target of BRL 220bn set at the beginning of his government.

Many critics argue that such adjustment is impossible at the national government level, given the budgetary rigidities. Close to 90% of the expenditures are mandatory. Of those, one quarter (including pensions) are indexed to the minimum wage, which is indexed to government revenue growth. Furthermore, healthcare and education expenditures are earmarked at 15% and 18% of revenues, respectively.

Nevertheless, Tarcisio believes that with proper political engagement, Congress can be convinced to pass budgetary reforms such as cutting personnel expenditures as a percentage of GDP and removing the indexation of expenditures to revenues, which would allow for a small primary surplus and room for infrastructure investments. Administrative reform and well-designed concessions would mobilise private capital as he did in Sao Paulo.

History suggests Tarcisio is right. Former presidents Cardoso and Temer managed to convince Congress to pass difficult bills to achieve solid fiscal consolidations with anaemic GDP growth. Recent structural reforms suggest the economy can now expand by 2.5%-3.5%, making it easier to steer the country towards debt sustainability. Furthermore, Tarcisio becoming the candidate, and winning the election in 2026, would bring an immediate positive confidence shock, boosting the BRL and lowering inflation expectations. This would allow for rate cuts and therefore lower interest costs. Given the primary deficit is relatively small, lower interest rates would go a long way to help restore debt sustainability.

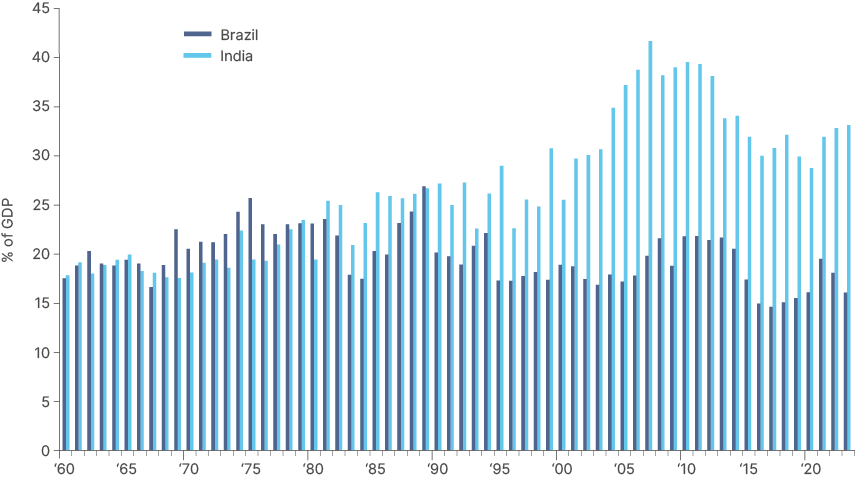

Once reforms bring fiscal balances back to an equilibrium, the country needs to build. Capex-to-GDP has been below 20% since the 1990s (see Appendix 1), which has fostered a tepid long-term structural growth profile, particularly in manufacturing sectors. There is nobody better than Tarcisio to lead a Brazilian infrastructure renaissance that would attract further capital from the private sector, kickstarting a new cycle of sustainable growth in Brazil. If capex-to-GDP can rise above 20% again within a credible budget, Brazil will be back on track.

Conclusion

Brazilian assets have become very cheap, as investors have priced in the risk of continued fiscal slippage and inefficient spending under tight monetary policy. This is a story that has played out before (Appendix 1).

But there is another way. With fiscal reforms and greater infrastructure investment, Brazil can establish a more stable growth profile. The 2026 elections offer a pivotal chance to reset expectations, restore confidence, and kickstart a new era of sustainable expansion. With Lula's popularity waning, the risk to reward ratio in Brazil is now attractive.

Appendix 1:

Economic background

Brazil’s economic development has been a story of stops and starts. Industrialisation took off in the 1940s and 1950s under a democratic regime led by Joao Goulart. The activity was largely state-led, however, and major state-owned enterprises (SOEs) Petrobras and Eletrobas (now private) were established. Protectionist policies and excessive external borrowing to fund capex led to expanding industry and growth, but ultimately soaring inflation, which reached 91% by 1964. By this point, Brazil was in economic disarray, and GDP growth had ground to a halt. Revolution ensued, and Goulart’s government was overthrown in a military coup d’etat which aimed, in part, to ‘complete the mission of restoring economic and financial order in Brazil.’

The 16 years of military dictatorship that followed were violent and oppressive. However, it was a period of strong economic growth, that became known as the ‘Brazilian miracle.’ Annual GDP growth averaged 10%, with technocratic developmental policies driving rapid urbanisation and industrialisation. Wage suppression helped boost export competitiveness. By 1980, 57% of Brazil’s exports were industrial goods, compared with 20% in 1969. However, the conditions supporting this growth boom were unsustainable. Centralised development crowded out the private sector, and heavy reliance on imported oil for energy was exposed by price shocks in 1973 and 1979, which led to Brazil amassing the largest debt burden in the world at the time. With global rates very high, Brazil’s debt again became unsustainable, inflation spiked to 100% and growth cratered. Democracy had returned by 1985, but could not revive a lost decade, with stagnant growth, frequent debt crises and hyperinflation, which peaked in 1993 at 2500%.

Under Fernando Cardoso’s leadership, Brazil’s economy stabilised and liberalised over the next eight years (1994-2002). Key institutional reforms, including the Real plan, inflation target regime, privatisations, and the fiscal responsibility law, set the foundation for the country to regain macro stability and growth. Institutions strengthened through structural reforms, but high rates began to weigh on growth before the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 led to capital flight from all emerging markets, including Brazil. The central bank tried to defend a crawling USD peg but ultimately eroded its FX reserves. Despite a USD 41bn loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1998, the peg was broken and the Real devalued nearly 70% in 1999. The currency had fallen another 100% by 2002, due to fears of Lula’s incoming presidency.

Nevertheless, Lula initially committed to fiscal responsibility and higher commodity prices allowed for significant growth and a deleveraging cycle. This period saw strong investment inflows and stable real GDP expansion. Strong GDP growth and currency appreciation from very weak levels led to phenomenal earnings-driven equity returns in both BRL and USD terms, with the IBOVESPA index rising over 40% annually between 2003 and 2007.

Prudent fiscal policies began to be eroded during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and were significantly damaged by Lula’s successor Dilma Rousseff, who was impeached for breaching the fiscal responsibility law right after winning her second mandate. Michel Temer then took over and steadied the ship, delivering important labour reforms, private sector deregulation and a solid fiscal consolidation – even with GDP growth at around only 1%. Bolsonaro then built on this platform, implementing the Plano Mais Brasil agenda, which included more pro-growth business deregulation and resource decentralisation. The government also passed a much-needed pension plan reform and privatised various SOEs, including Eletrobas. Unfortunately, fiscal discipline was forgone during the pandemic and at the end of his government in an attempt to get re-elected. Nevertheless, Temer’s and Bolsonaro’s reforms were enough to put Brazil on a better equilibrium, allowing macro stability and economic growth.

Appendix 2:

Brazil vs. India GDP Capex/GDP and GDP growth

Indeed, capex-to-GDP trended down from 1990 until the GFC, when GDP dropped, thus raising the ratio. In emerging markets, rising capex-to-GDP is one of the best harbingers of future growth. For example, the divergence of Brazil’s GDP growth from India’s closely tracks the divergence of the two countries’ capex/GDP spending. Of course, India’s superior demographic dividend has played a role. But India’s capex surge from 1990 onwards has been a key driver of very strong average growth since, whereas Brazil’s weakening commitment to infrastructure investment has culminated in a more tepid long-term growth profile.

Fig 6: Capex as a % of GDP

Fig 7: 10-year moving average GDP growth